Traditional popular culture, in its various material and spiritual forms and expressions, is the essential object of the Ethnographic Atlas of Cuba. It will be a heritage of great significance for all the people, one in which the values of nationhood that, in a process of dynamic recreation, nurture and strengthen national identity, are embodied.

Material culture, finding expression in this work through cartography, includes: rural settlements, houses and rural auxiliary facilities, rural furniture and objects, foods and beverages of the rural population, agricultural tools, rural transportation, sea fishing gear and vessels, and traditional handicrafts. In the field of spiritual culture, the following may be included: traditional celebrations, traditional music, traditional dances and traditional oral stories. The study of ethnic history has been a necessary requirement for our work.

Specialists from the Ethnology Department of the Center of Anthropology, the Center for the Research and Development of Cuban Culture Juan Marinello, and the Center for the Research and Development of Cuban Music accomplished this work. Cartographic elements were contributed by the Institute of Tropical Geography.

The compilation of the Atlas, started more than twenty years ago, was necessary because of many reasons. Firstly, there was a lack of systematic studies on traditional culture with an ethnographic approach and comprehensive results for nationwide issues. For a long time, cultural expressions, the fruit of the people’s lore, were relegated to the area of phenomena in which there was no official interest. Only a small group of researchers, whose main representative was Fernando Ortiz, engaged in this enormous task in the first half of the 20th century, contributed to its expansion and, at the same time, established its deep implications for Cuban culture. The work of these forerunners still maintains an untold value and many of its aspects have not been surpassed. However, since their work was rather individual and lacked the required economic support, their results could not encompass popular creation in all its wealth and variations.

After 1959, institutions with new approaches and perspectives for the study of Cuban culture were established. However, devoting individual and collective efforts to specific aspects of culture, with various historical, social and geographical scopes, did not contribute for a long time to the emergence of more comprehensive studies. Also, the revolutionary process gave way to new elements. Rapid economic, social and cultural transformations created a dynamics of change in daily life and traditional cultural heritage that made the disappearance of many of their expressions probable under the new socioeconomic and cultural conditions, since a large part of the elements in which they were based had undergone transformations. The need for collecting, ordering, analyzing and classifying the valuable material in hand became an evident means to recapture, revitalize and leave a record for the future generations of all that immense popular wisdom. It also was a required commitment and a form of paying tribute to the foreruners of Cuban Ethnology.

These, among others, were the circumstances in which the research for the Cuban Ethnographic Atlas began. The sections into which it is divided are based on the above mentioned topics.

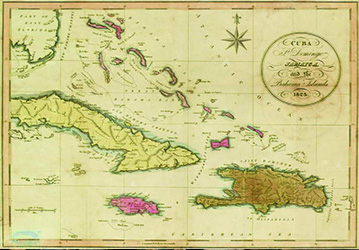

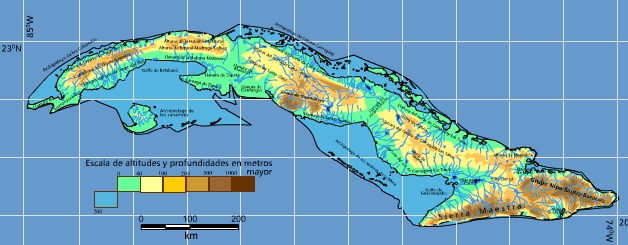

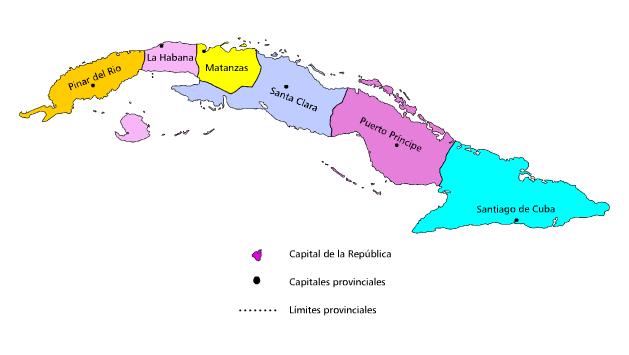

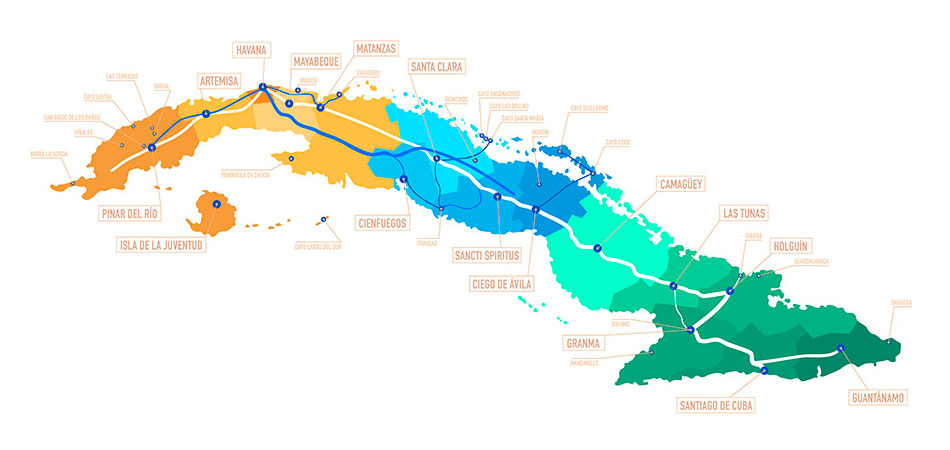

The Atlas also contains a set of maps offering an overview of the physical and geographical characteristics of Cuba and of its political and administrative divisions in various historical periods, since they have been the basis for its cartography; in the Atlas, the divisions established in 1976 have been used the most, since they are the ones in force today and when the research was being made. The country was divided into 14 provinces, 169 municipalities and a Special Municipality.

Our work was based on the notion that everything created by men and women is culture, above all creations expressing their feelings, the way they are and think, the way they live and the knowledge they hoarded throughout History and fulfil important functions in the satisfaction of the spiritual and material needs of their creators and bearers. It is a heritage of popular expressions and representations maintained, recreated and transmitted in an age-old process that made it traditional and in which transmission processes such as words and examples are used; in brief, it is a study of the cultural features and expressions that distinguish us as an ethnic group but that, at the same time, present the edges of elements we share with other peoples.

Traditional popular culture is a dynamic and creative phenomenon. Thus, research paid special attention to the way it changed in the course of history. Also, each phenomenon was studied not only as an expression in itself, but in is full meaning as an interceding element in the social relationships established by men. Relationships with the natural, sociocultural and economic environment in which it operates and its close dependency on the ethnic traditions were equally taken into account. All these factors contribute to the understanding of the historical and ethnogenetical processes that formed the Cuban people, since culture carries within itself the marks of that history and of links of kinship with other human conglomerates. This information is extremely valuable for the knowledge of the Hispanic and African legacy in Cuban culture.

As a way to understand some of the specific traits of the cultural clash that took place and the later transculturation process, the starting point in the study of our ethnic history is a characterization of the native communities that inhabited Cuba at the arrival of the Spanish and the main areas where Indians and Spanish entered into contact. An ethnodemographic study offers the number and participation of the various immigrant groups that entered the country throughout its History, since the arrival of the Spanish until the 20th century. This way of dealing with the problem contributes to systematize the considerations on the ethnic origins of the cultural expressions studied and to give them a theoretical foundation.

From the beginning, it was decided that the results obtained would be presented in two main forms: through this Atlas, where the topics are shown in their spatial distribution and historical dynamics, and through a set of monographic texts containing a historical and ethnographic analysis of each phenomenon, as well as of the main contributions in the field. Both parts, although they are complementary and together offer a comprehensive view of the topic, are relatively independent.

The gathering of information intended to achieve those two large purposes. Thus, it was necessary to take into account what has already been said about the inadequacy of research on specific aspects of popular culture in its territorial distribution and the lack of ethnographic museums and archives that would serve as a source for historical studies.

It was essential to create a research program, in which field work and various methods and techniques would be the main avenue for ethnographic research. That is, everything related to methodology was determined by the available sources and by the classic approaches used in the field of Ethnology. Within this general plan, each topic would receive the special treatment its specificities demanded. Only general principles would be stated.

Concerning material culture, the study began by ethnographic expeditions to nine of the fourteen provinces in the country (East, Center and West). Following a radial displacement method, a given number of localities were visited, previously selected according to indicators of historical, geographical, economic and cultural nature. In this phase of the work, through participatory observation and interviews with specialized informants -- most of them of an advanced age and natives of the area under study -- the necessary qualitative material for the elaboration and development of preliminary thematic typologies was gathered. The research team in each expedition included photographers and sketchers for graphic testimonies of the evidence found.

Once this phase was concluded, questionnaires were prepared and, after testing them through a pilot plan, a national survey was conducted, making possible the definitive establishment of typologies with a high scientific standard and the obtention of the necessary quantitative data for cartography. Typological and thematic sketches on the research accompanied the survey questionnaires because of the accuracy this work demanded.

An extended and intense work of ethnographic research was also carried out throughout the country to gather information on spiritual culture and handicrafts, with the use of the same techniques and procedures. But in this case, there was a significant participation of the specialists in cultural studies of the Ministry of Culture in each province and municipality. Their knowledge of the area in which they worked and the training they received through seminars, colloquies and lectures, where the purposes of the work and the tools that would be used were discussed, contributed to the collection of a wide volume of data, that were later processed by the researchers in charge of the guidance and implementation of the work.

What was specific in this case was that the studies on settlements, housing and auxiliary facilities, furniture, foods and drinks, tools and means of transportation were made in rural areas, where these expressions are preserved with greater strength and less contamination, while the spiritual culture -- celebrations, music, dances and oral traditions -- and handicrafts encompassed rural and urban areas. sea fishing gear and vessels were researched in all the fishing communities in the country. Information obtained was automatically processed.

The study of rural areas always included the scattered population and that living in townships. All the social and class strata in the Cuban countryside were covered: independent peasants, those grouped in Credit and Service Cooperatives or in Agricultural Cooperatives and workers linked to state agricultural plans. The composition by sex of the interviewees, in urban and rural areas, depended largely on the specific contents of each topic.

For the design of the research and for the testing and adequate interpretation of the data obtained directly in the field the use of written data was important.

The collection, analysis and classification of information, and the elaboration of the typological criteria that made the drafting of the ethnographic maps possible, followed a set of basic indicators, having to do, above all, with the function of each expression of traditional popular culture in daily life and in the system of human social relationships. Whenever feasible, the motivations for their development and the underlying ethnic background are offered as elements enriching the classification.

In the case of material culture, the materials, techniques and procedures with which the various objects were manufactured, morphological aspects and the manner in which they function were taken into account. In the expressions of spiritual culture, the establishment of the dichotomy between their lay and religious character, very linked to their ethnic background, was of great value. Thus, the criteria of functionality, central to the analysis, was enriched.

All this allowed for the definition of a set of types, subtypes and typological variants that, after finding expression in maps reflecting their spatial distribution and historical dynamics, offers a vast panorama that may be used for many interpretations, whether past, present or future.

For some topics, data gathering began towards the end of the ′70s; for others, at the beginning of the ′80s, and it ended between 1988 and 1990. This is the top date for the results presented. The historical periods into which information has been divided have depended on the specific requirements of each phenomenon and of the scope on the available sources.

In the section on ethnic history, it was necessary and feasible to go back to the initial moments of the process of ethnogenesis. Data from cesus and archives were used for this purpose. Also, the problems of rural settlements are approached in the general and reference maps and some maps on spiritual culture present documental and bibliographical information on the colonial period, particularly of the 19th century.

In the sections where cartographic information was obtained through a national survey, the dynamics of each phenomenon are expressed in two chronological moments: before 1959 and in 1988. The mathematical and statistic analyses to which the data were submitted contributed to the elaboration of frequency indicators, showing the degree of intensity of each expression of the traditional popular culture in the different provinces of the country. In addition to the qualitative valuation, a percentual quantitative element is offered: High (60 % and more), Medium (from 30 % to 59,9 %), Low (from 10% to 29,9 %) and Very Low (from 0,1 % to 0,9 %).

In other cases, especially those having to do with spiritual culture, the information gathered made it possible to express the great variety of cultural expressions that developed with the purpose of satisfying the most diverse spiritual requirements of men and women in the various stages in Cuban History. That is why information was included on expressions that had sometime ago had a traditional popular character, but that were not in place at the moment when the research was made because of various socioeconomic and cultural transformation processes; to indicate the presence of the phenomenon and its dynamic of change, the indicators In Force and Not in Force were used. In the section devoted to fishing, some examples that had disappeared and were rescued through a method of ethnographic reconstruction, from information offered by old fishermen and craftsmen, were included. These have been the general procedures. Throughout all this work, the reader will be able to find the specific traits of each topic.

The results obtained show the wealth and regional variation of our traditional popular culture, due to the presence of different historical, socioeconomic, geographical and cultural factors, making it a very important material for future regionalization projects.

It was possible to verify the force of traditional popular culture, as well as the usefulness and value that its expressions still have for wide social sectors; this confirms its deep insertion in national culture. Traditions have been maintained even under the influence of factors that have made a strong impact on it, such as massive literacy and the effects of national scientific and technical advancements and, in general, the transformations of the natural, social and cultural environment in which they had for generations been based.

It was once more seen that elements with a given ethnic charge, with very specific functions in daily life, are less likely to sharp changes and give proof of a great adjustment and survival capacity, even in the midst of deep socioeconomic transformations. They are an important part of the historical experience of the peoples and are the basis of their self-awareness of a common origin, so important for their operation and reproduction.

As to underlying ethnic influences, it must be acknowledged that their delimitation was difficult in the cultural expressions under study. This has to do with the great ethnic diversity intervening in the process of transculturation and the specificities of the insertion of each group in the Cuban natural, economic, social and cultural environment. In this context, it must be remembered that the historical memory of their current bearers is also the fruit of that process of transculturation that, because of many reasons, has caused that the references to original elements are at times very vague. At times, these references have even been forgotten and it was necessary to resort to compared Ethnology. What is possible to assert is that they are Cuban expressions, maintained, recreated and transmitted by persons born in Cuba.

The heap of factual information, gathered during more than ten years of laborious and systematical field research, and its processing, classification and typologization, is a source of invaluable wealth for scholars of Cuban culture undoubtedly surpassing the purposes of this work. Synthesis and generalizations of the most meaningful elements and characteristics of the studied phenomena are offered in a set of maps. All this material is kept in the funds of the archives of each of the institutions that took part in the elaboration of the Atlas.

In addition to their scientific value, these results are of great practical importance. They have been used in countless plans for cultural revival, as a source for the elaboration of textbooks, graduate courses, didactic films and museums assembly, to contribute to the knowledge and strengthening of cultural identity in its regional and national expressions. The specialists that carried out the research during all these years have participated in scientific events, exhibits, national and international fairs, colloquies and seminars, adequate places for the exchange of experiences and knowledge.

Their joint work during these years with institutions and research and cultural promotion centers has had an important impact, not only in the field of cultural revival, whose fruits are presented in the various sections, but also in the rescue of the awareness and importance this has for cultural work.

The information appearing in the Atlas should add itself to the existing potential for solutions to important local problems, where the massive and, at times, indiscriminate implementation of technical innovations has not offered the expected results. In this way it can contribute to the possible implementation of the advantages of the traditional cultural heritage and the economic value that the rescue of some traditional practices may represent.

The Atlas exceeds the framework of Cuban culture to reach the Latin American and Caribbean area, where common processes have taken place with the intervention of ethnic components that are very similar to those that participated in the emergence of our people, in historical, socioeconomic ecological and cultural conditions with their own characteristic traits. A conceptual theoretical and methodological model that guaranteed the strictest accuracy and scientific standards of the information gathered in their analyses and interpretations was created for this work. Its practicality turns it into an instrument that may be used in other areas where research of this type is conducted.

As the result of this research, we today have a cartographic work that, for the first time in our country, provides a nationally systematized ethnographic study with a wide range of expressions of traditional popular culture and the Cuban ethnic history.

The Atlas consists of thirteen sections, in agreement with the researched topics and has 238 maps. The cartographic bases of Cuba are presented in scales of 1: 3 000 000; 1: 4 000 000 and 1: 5 000 000, and, according to the the specific traits of some topics, other scales for various areas of the World that have to do with the processes under study have been included. Each section is preceded by a text offering information and explaining fundamental concepts for the understanding of what is cartographically expressed. The maps are accompanied by a set of engravings, photos, drawings, tables and texts that serve as illustrations of their contents.

Given the specialized nature of this work, although they follow the general principles of Cartography, and particularly of ethnic Cartography, the methods of representation used are a contribution in that area and are new in these projects. Symbols capable of expressing phenomenon correlations, spatial distribution and historical dynamics were used. The combined use of cartodiagrams, cartograms and out-of-scale symbols, to offer a comprehensive view of the phenomenon dealt with in each of the maps, has been of a great help. Also, the requirements of Cartography were combined with those of the topics that were to be cartographically dealt with.

A significant experience was the joint work of cartographers and ehnologists. The previous preparation of the latter in the cartographic representation techniques, not only allowed them to draw author sketches, but also to maintain a constant exchange of ideas for the attainement of the objectives.

Whenever possible, the terminology coined in popular culture to identify the expressions under study and to facilitate the understanding of terms, above all of terms having to do with Cuban reality or, in the case of the ethnic names used in Cuba for slaves from Africa, that were very different from their original ethnic names, were respected.

The diversity of topics included in the Atlas made interdisciplinary work one of the features characterizing it. The work of ethnologists, musicologists and cartographers had the collaboration of historians, linguists, sociologists, geographers, biologists, food nutritionists and art teachers, inter alia. The design of the research and all the process of information gathering and preliminary analysis in the sections of material culture had the collaboration of technicians and specialists of the Miklujo Maklai Ethnography Institute of the Academy of Sciences of the former Soviet Union.

In this introduction it would be virtually impossible to mention all those persons and institutions that contributed to the various phases of the reseaarch. Enough it to say that we received the support and the direct participation of technicians and specialists of the Cuban Academy of Sciences and of the Ministry of Culture, and that this collaboration was extended by all the organizations in each province and municipality of the country. Technicians, teachers, undergraduates and professional of many diverse disciplines helped in data compilation. The National Association of Small Farmers (ANAP), that offered us all the possibilities to carry out our field work among the rural population, deserves a special acknowledgement. Our warmest thanks go to all those that were the nourishing source of this research and offered all the required information in rural and urban areas: peasants, workers, housewives, craftsmen, fishermen, musicians, dancers and religious people.

Dr. Juan A. Alvarado Ramos

- Introduction

- » Ethnic history