Music plays a very important role in the knowledge of traditional popular culture, since it is present in every stage of the human life cycle.

Immediately after men and women are born, they listen to their mother′s lullabies; later, they sing in their childhood games and, as adults, they do so every day, especially in moments of happiness or of religious fervor.

The study of traditional popular music contributes to deepen into the psychological and sociological mechanisms that impel human beings to preserve their cultural heritage, since music is so intimately linked to their own lives. Traditional music forms part of the thoughts and actions of men and women and allows them to express their ideas and feelings. In this sense, traditions and habits contribute to transmit and preserve vivid forms of expression, so every person considers himself or herself an active part of his or her community and may thus satisfy their spiritual needs.

If this integration does not take place, individuals suffer a process of uprooting that may bring them to alienation. Thus the importance of preserving traditional cultural values and music as an indissoluble part of it.

In the present study, when analyzing musical developments in various historical periods, the evolution traditional popular music has undergone in its structure and in its ensemble of instruments becomes evident and its prevailing characteristics are thus identified.

All the music that is the object of our study is considered Cuban, although the ethnic origins of some expressions may be identified in spite of the deep transculturation processes that have taken place. These processes have been continuous and carry within themselves elements of various origins.

The morphological analysis of each genre has contributed to the knowledge of these evolutionary processes and allows to elucidate the different variants or styles of each musical expression.

Our music has been researched by outstanding specialists, but most of their work has been based in cultural traits found in the Western part of the country, especially in Havana, as if music were homogeneous throughout the national territory.

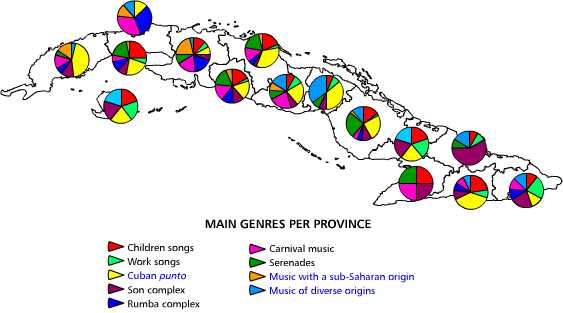

Also, studies tend to be partial, since only some topics have been studied, among them the music of African origin and the son, while other genres have been less dealt with -- work songs and carnival music, for example. In the present research, we tried to overcome this flaw by covering a wide range of genres and analyzing the way they are found throughout the national territory, and in urban and rural areas, with the purpose of identifying regional differences.

Our classification combines several factors. First, the criteria of the function of music in the human life cycle was used. Secondly, genres, musical styles, and vocal and instrumental ensembles were analyzed. As to religious music, it was necessary to determine its ethnic origins since each ethnic group has its own musical expressions, language and instruments.

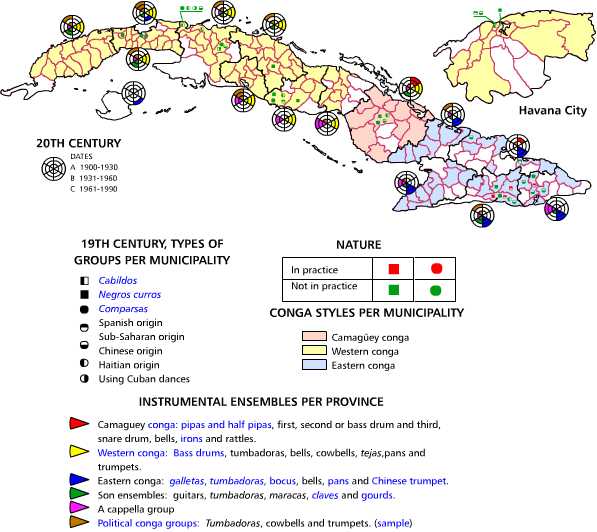

Historical aspects, such as the existence of musical expressions or groupings from the 19th century, generally obtained from archives, are included in various topics. The chronological evolution of instrumental ensembles in the present century, with an operative division into three thirty-year periods, was established for some genres. The first period (1900-30) includes the establishment of the republic and the American presence; the second (1931-60) covers the fight against the republican governments that ends in 1959 with the triumph of the Revolution; in the last period (1961-90), the revolutionary government is in power. Music does not escape the influence of these historical changes; political congas, for example, change their contents in accordance with the prevailing situation: liberal chambelonas against conservative chambelonas in the two first periods; congas supporting the Revolution in the last one.

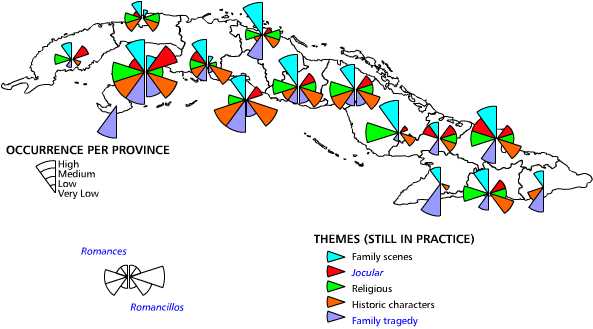

For the cartographic presentation of these developments, we start by the music linked with childhood, that is, children songs. The main typologies follow the growth of children: lullabies, games for babies, children songs, sung games and rondas. Also, the poetic forms used in these songs, romances and romancillos -- mostly sung as rondas and studied as independent poetic forms -- are included; their topics were divided into: family, funny and religious scenes and those having to do with historical characters and family dramas. Carolina Poncet′s suggestion in her book El romance en Cuba was followed in this classification with the addition of a differentiation between romances (octosyllabic lines) and romancillos (six and seven syllable lines); a cycle of romancillos on doves is also included.

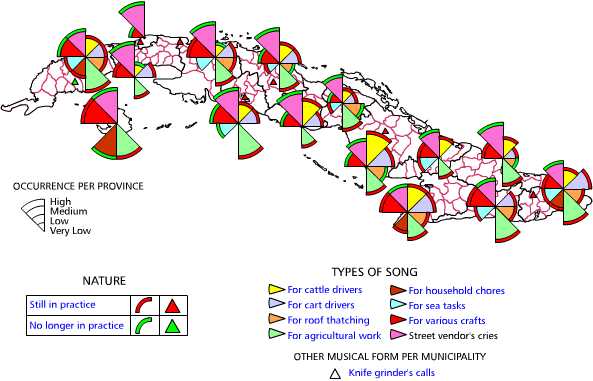

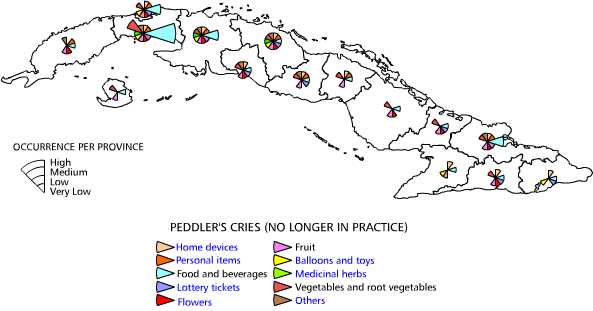

Work songs are divided into: songs to drive herds and cartdriver, roofing, tilling, home and sea songs, as well as knife grinder′s calls and vendor′s cries, with the various products they offered.

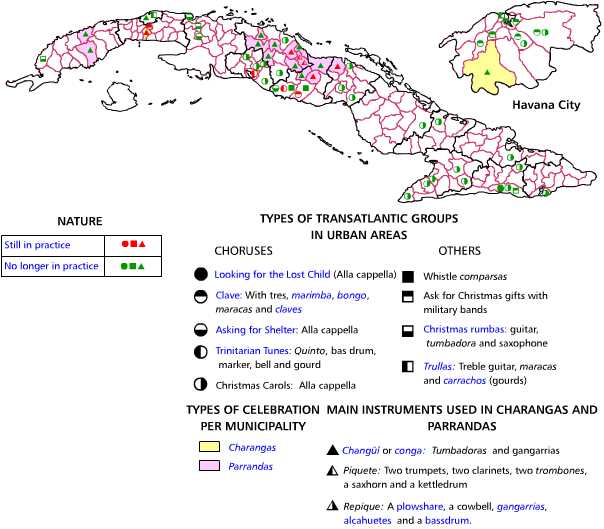

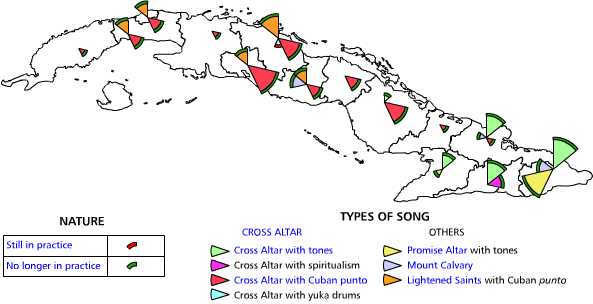

In religious music, a distinction is established between music with its origin in Catholicism and that with a sub-Saharan origin. In the first group, Christmas music and May Cross Altars are to be found. Choruses singing Christmas carols in churches, private homes or in the streets form part of the first group -- the trullas, on foot or horseback, groups that with a "treble guitar and a gourd under their arm" went down the streets singing songs having to do with the celebration. There were also the clave choruses and Trinitarian tunes, which competed in Christmas time. Christmas charangas and parrandas, where the different neighborhoods in town prepared congas with provocative or triumphant lyrics, complete this group. When the May Cross Altars were held, choruses competed among each other for the objects that were placed in the altar.

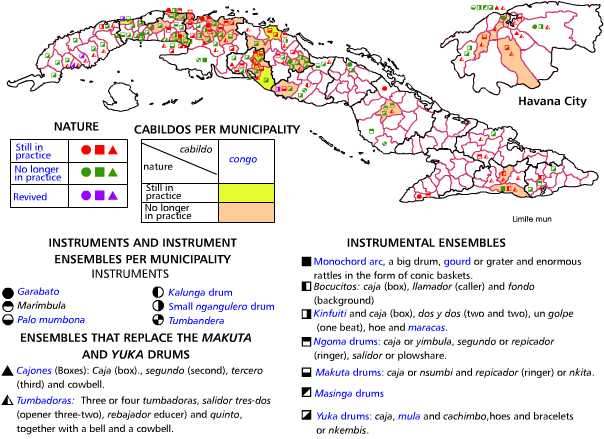

Music with a sub-Saharan origin was divided according to its various ethnic roots, as was already explained, since each group has its own language, deities, myths, rites, songs, beats and instruments. This music is characterized by being eminently religious even when, at times, its instrumental ensemble may be used also for lay music; this is the case of the Congo yuka drum, that is used for songs in the palo monte rites (mayombe, briyumba and kimbisa) and to dance the festive yuka.

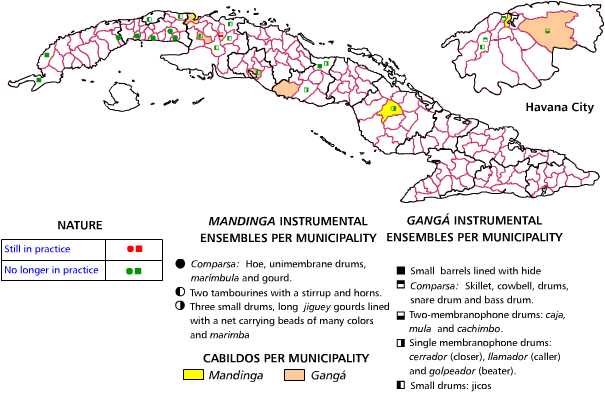

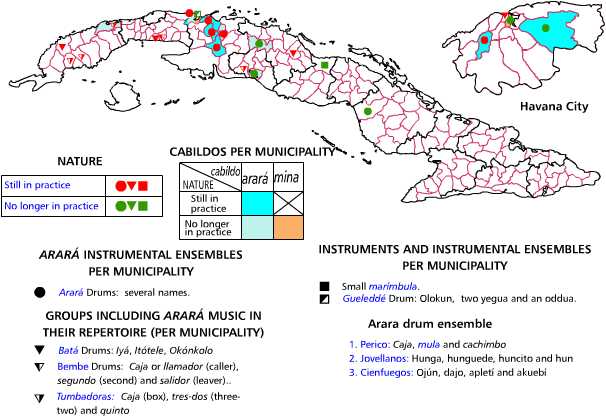

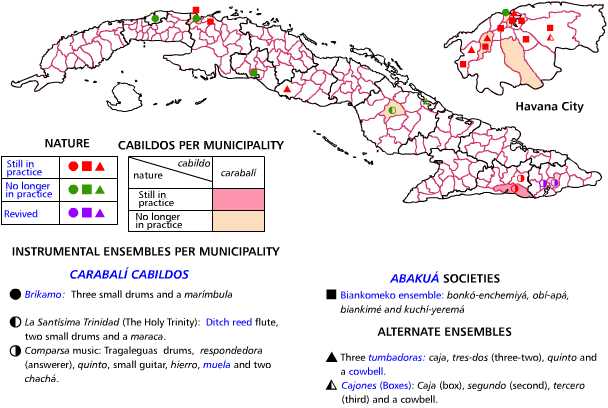

Musical expressions of Ganga and Mandinga origin were grouped in a map taking into account various factors, such as geographic origin and some cultural similarities; the same was done with those of Arara and Mina origin. Carabali music includes the music of the cabildos and that of the Abakua societies. Musical groups of Bantu or Congo and Lucumi origin are presented individually. Congas encompass the musical groups of (historical and present) cabildos that are still in force today and those of Yoruba or Lucumi origin (including Iyessa).

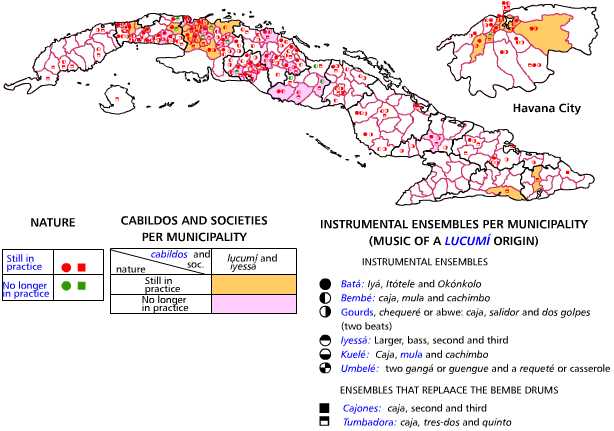

This last ethnic group has a religious expression known as santeria, very extended among the Cuban population. Its music shows an enormous complexity of forms and instrumental ensembles stemming from the syncretic process among the various cults in each region.

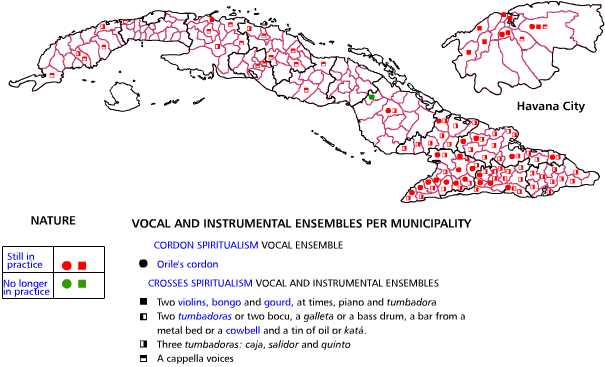

Spiritualism has a strong impact in the above mentioned religious expressions and, because of the growth it has had in its gradual extension from East to West, also in its music; the music of cordon spiritualism and of spiritualism crossed with santería and palo monte is also studied.

In general, towards the Western area, there is a prevalence of the sub-Saharan influence that can be seen in the genres, instrumental ensembles and music. The variety of beats to each deity, the lyrics in original languages (Yoruba, several Bantu dialects and others) and the use of drums such as bata are preserved in a rather orthodox way in this region.

Towards the center of the island, these expressions are punctually located and do not extend to great areas. In the East they again are extended, but with a qualitative difference from those in the Western area. This is evident above all in the instrumental ensembles, since the drums that are specifically used for each ritual are replaced by tumbadoras, bocus and bombos and the beats to accompany the songs to the deities are fewer. The lyrics of the songs have a minimum of African terms and Spanish is more widely used.

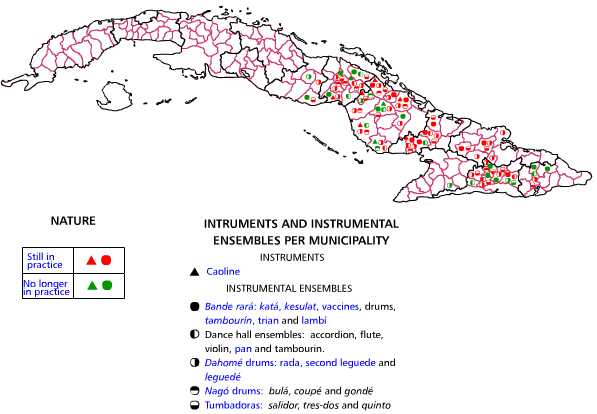

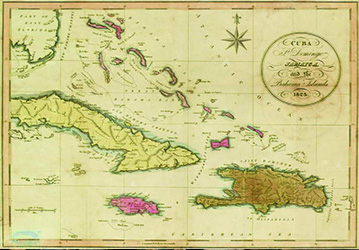

Music from other countries, such as Haiti, was also studied; because of its significance, dominating the Eastern area, from Ciego de Avila to Guantanamo, French Haitian influence should be added to that of Africa and Spain, the accepted main roots of our traditional music. This influence finds an expression in various musical genres, such as the conga Oriental -- with a characteristic beat based on the rhythmic cells of the Mason beat from the French-Haitian tahona -- and santeria music, that includes deities, songs and beats from the Haitian voodoo.

There were two important historical moments in this marked cultural influence. First, towards the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th centuries, when the Haitian revolution erupted and the first massive migration from that country to Cuba took place. Its most studied musical and dancing expression was the Tumba Francesa; second, in the first decades of this century. Research on this last migratory wave has mostly centered in the Holy Week Bande-Rara, but these groups were the bearers of diverse musical expressions that are not very well known.

Both migratory waves settled mostly in the Eastern region and exercised a profound influence on their music, which is very different from that in other regions. For its better understanding, music of Haitian origin is divided into two chronological moments: 18th and 19th centuries and 20th century. Vocal groups and instrumental ensembles are highlighted; their historical dynamics and their lay or religious character are presented in both cases.

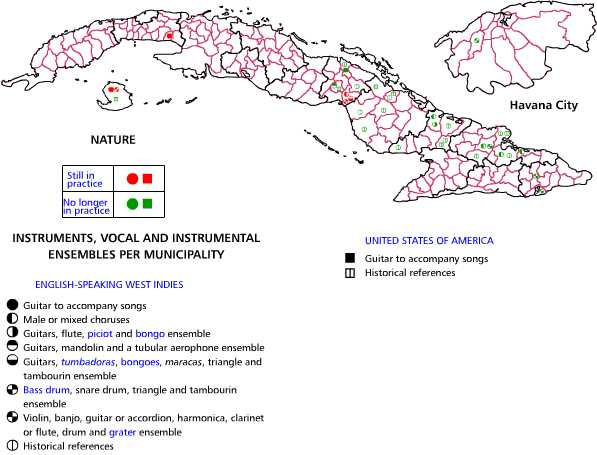

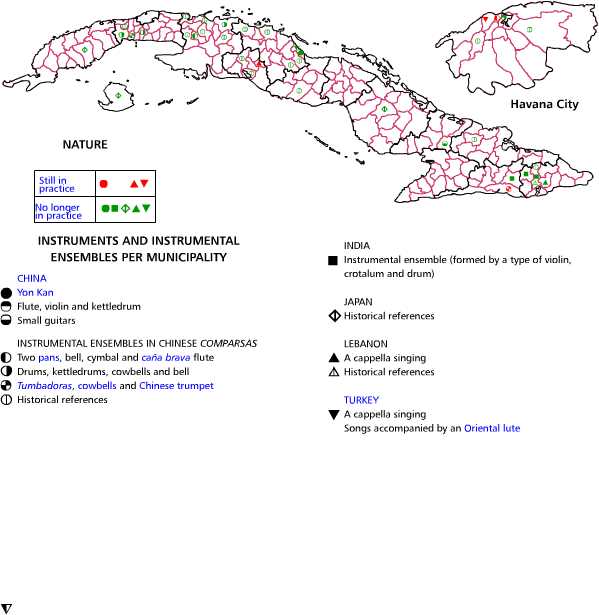

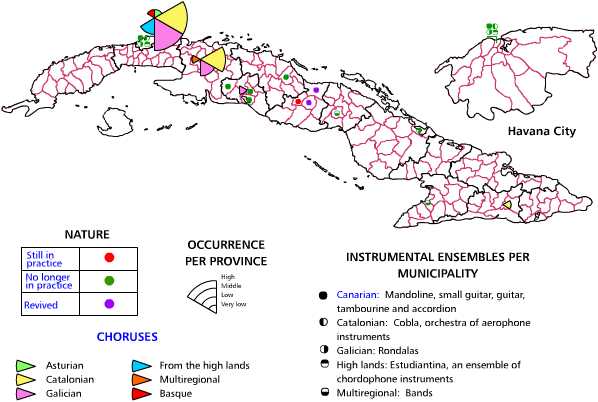

Musical expressions of other migrant groups that arrived in Cuba between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th are divided by nationalities: English-speaking West Indies and United States of America, Asia, the Middle East and, lastly, Spain. Vocal groups and instrumental ensembles, whether still in use or not, and historical references are also included.

The analysis of this information shows that music from the English-speaking West Indies -- Jamaica, Barbados, Cayman Islands, among others -- had a certain impact in some areas in Cuba at the beginning of the 20th century, but gradually disappeared from the Cuban context. Today there are only two groups in existence: one in Baragua, province of Ciego de Avila, that tends to preserve West Indian cultural traits, and another in the Isle of Youth, that makes use of Cuban musical elements in its evolution.

Of the music from Asia and the Middle East, only Chinese music achieved a larger expansion; in Havana City, musical groups composed by Chinese men and woman and their offspring have survived. Some Chinese instruments have been used by musical expressions originated in Cuba, as was the case of the little Chinese box used in rumba and the Chinese horn of the Conga Oriental.

Music with Spanish roots is to be found throughout the country, mainly in children and work songs. But a closer look reveals that it is stronger in the central provinces -- Villa Clara, Sancti Spíritus, Cienfuegos and part of Ciego de Avila -- where the peasant punto, Christmas parrandas and other genres with a Spanish origin are very rich and varied. The preservation of the choruses of the May Cross Altars and of archaic romances in isolated spots of the Eastern region, such as Baracoa, is also of interest.

The impact of groups that arrived in the last migratory waves at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries was mainly seen in choruses from several Spanish regions concentrating in Havana and Matanzas, where clave choruses, imitating Spanish ones, were established. As a result of cultural interaction, rumba choruses, in turn, imitated clave choruses. It is important to highlight the presence of instrumental ensembles of Canarian origin in the central area, where some of them are still heard.

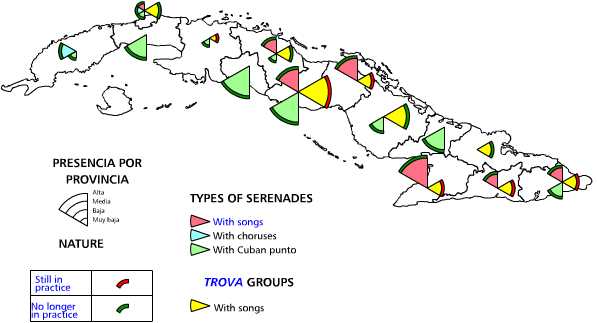

Festive musical genres include: songs, represented by serenades and peñas de la trova (trova circles), the Cuban punto, the son and rumba complexes, and carnival music.

The study of traditional Cuban songs is focused from the point of view of its social use in the form of serenades --with its genre variants -- and the peñas de la trova, as places where songs that were created towards the end of the last century are preserved.

To define the son and rumba complexes, Argeliers Leon examines the diversity of expressive forms these genres take in the various regions.

The process leading to the formation of these genre complexes may be explained through the analysis of all the structural elements that, decomposing and recomposing in successive historical moments, contributed to the establishment of the stylistic and instrumental forms they today have.

For their better understanding, the various genres forming them and, in some of them, the styles usually used in performing them have been defined and differentiated.

The conga and the peasant punto are not considered genre complexes, but independent genres with several styles. The first one is at times considered a genre within the rumba complex, when it actually is a musical genre with its own genesis. This misunderstanding appeared because the comparsas in Havana and Matanzas were organized by persons that also took part in clave and rumba choruses, but in other provinces conga developed totally apart from rumba.

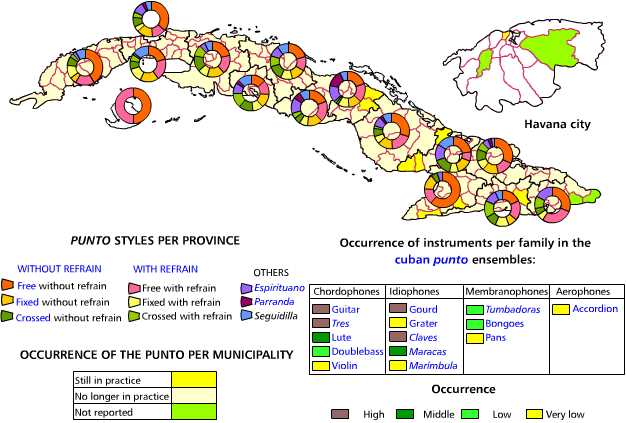

The peasant or Cuban punto is classified by some authors as a genre complex, even when it does not include several genres -- as is the case of the son and the rumba -- but only different styles.

The following styles may be identified: free, fixed, crossed, Spirituan, parranda and seguidilla. Modalities with and without refrain can be found in the three first ones. At the beginning, they were associated with geographical areas, but today there has been an expansion of the free style without refrain used in the controversias, but towards the north of the central area Spirituan and parranda styles prevail.

Groups with very diverse instruments, but always with various sound levels, accompany this genre and those of the son complex. The most widely used instruments are shown in tables by instrument families.

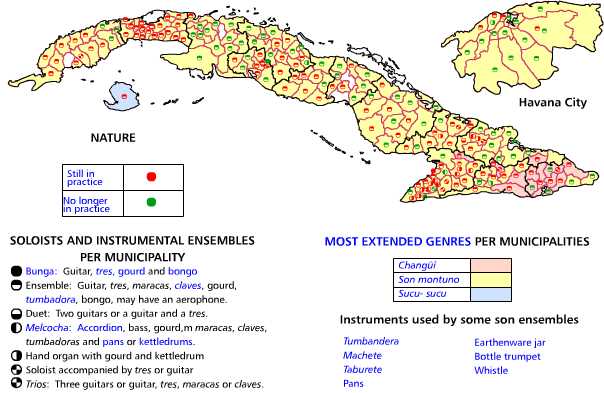

Son montuno, sucu-sucu, changui and the instrumental ensembles these genres use appear in the son complex. These genres, in turn, have stylistic variants (the nengon in the changui is a case in point). Because of its extension and force throughout the country it is undoubtedly the most representative genre complex in Cuban music.

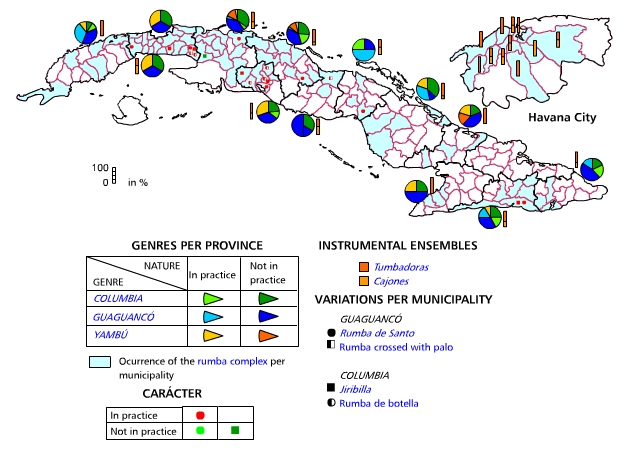

The rumba complex includes the columbia, the guaguanco and the yambu. There are several styles of guaguanco, among them the rumba de santo and that crossed with palo. Important styles of the columbia are the jiribilla and the rumba de botella; boxes and tumbadoras are very commonly used as instruments.

Carnival music includes the comparsas that began in the 19th century and instrumental ensembles used in the 20th.

Spanish, Chinese and Haitian comparsas and African "tangos", with their various musical and instrumental forms, were an early influence in the present Cuban congas and comparsas. They all changed very much during the 20th century until the present conga emerged, where instruments such as the bombo and the trumpet -- originally used by military instrumental bands accompanying some comparsas -- and others such as frying pans and Chinese horns, are played. The changes conga has undergone in the various regions have contributed to the emergence of different styles, among them Camaguey, Eastern and Western styles.

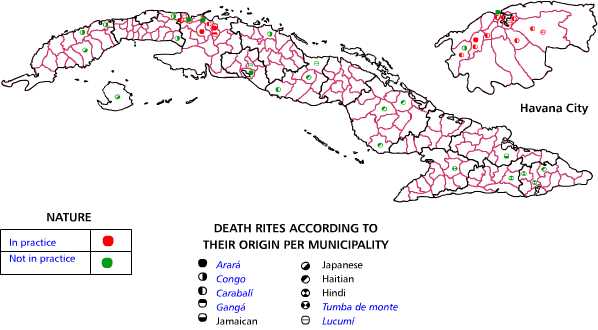

As an end to the life cycle, music related with death is presented. Groups that held or still hold funereal rituals or commemorations accompanied by music were identified. These are rituals derived from African religious beliefs.

Artistic projections drawn from the revival work undertaken together with the data gathering process for the present study are analyzed at the end of this section.

Lic. Marta Esquenazi Perez

Maps

-

Children songs

-

Children romances and romancillos

-

Work songs

-

Street vendors cries

-

Christmas music

-

Altar music

-

Music with a mandinga and ganga origin

-

Music with arara and mina origins

-

Music with a carabali origin

-

Music with a congo origin

-

Music with a lucumi origin

-

Cordon and crossed spiritualism music

-

Music from haiti. 18th and 19th centuries

-

Music from haiti. 20th century

-

Music from the english-speaking west indies and the united states of america

-

Music from asia and the middle east

-

Music from spain, end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries

-

Serenades and traditional trova

-

Cuban punto

-

Son complex

-

Rumba complex

-

Carnival music

-

Music having to do with the death

-

Revivals and artistic projects

Videos

-

Tenth-verse improviser singing cuban punto (country music)

-

Chorus of cross altar in Guantánamo

-

Invocation to Sarabanda, deity of palo monte, Guanajay

Examples

-

Children songs

-

Children romances and romancillos

-

Work songs

-

Street vendors cries

-

Christmas music

-

Altar music

-

Music with a mandinga and ganga origin

-

Music with arara and mina origins

-

Music with a carabali origin

-

Music with a congo origin

-

Music with a lucumi origin

-

Cordon and crossed spiritualism music

-

Music from haiti. 18th and 19th centuries

-

Music from haiti. 20th century

-

Music from the english-speaking west indies and the united states of america

-

Music from asia and the middle east

-

Music from spain, end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries

-

Serenades and traditional trova

-

Cuban punto

-

Son complex

-

Rumba complex

-

Carnival music

-

Music having to do with the death

- Traditional celebrations «

- Traditional popular music

- » Traditional dances