Throughout History, dancing has been a means through which men and women have satisfied their spiritual needs. Since ancient times, these bodily expressions have maintained a close link with life, not only as a form of spiritual satisfaction, but also for the fulfillment of important social functions, as a means of communication and as a way to master the forces of Nature.

This type of dance existed in the Cuban territory since the arrival of the Spanish colonizers. However, contrary to what happened in the rest of the Americas -- where native populations, larger and with a higher cultural development could survive the conquest -- in Cuba most of the dances forming part of the areito gradually disappeared as the native population diminished. The same thing happened with other spiritual expressions.

Thus, in contrast to the other Latin American countries where pre-Hispanic culture was a main source for traditional dances, Cuban dances are the result of a long process of contributions by various ethnic groups, mainly from regions in the Iberian Peninsula, the Canary Islands and sub-Saharan western Africa. Later, migrations from some regions in China and the Caribbean (mainly Jamaica and Haiti) were added. Dance elements of Hispanic tradition and others from various African ethnic groups began to arrive in Cuba in the 16th century.

Although most of the dances from several European regions had to do with religious celebrations -- whether in honor of the patron saint or in Altares de Cruz -- they lacked religious character, since their essential purpose was the establishment of social relations and a cohesion among the individuals while contributing to their enjoyment and entertainment. They are fundamentally danced in couples favoring courting and interaction between persons of different sex.

All dance expressions brought by the various migrant groups during the early centuries underwent a process of adaptation to the new social, economic, political and territorial conditions and thus expressions such as the zapateo -- with its variants -- and others that were actually Cuban, such as the dancing forms derived from the contredanse, left the dance halls and became a part of our heritage.

Sub-Saharan ethnic groups, also the bearers of rich dance traditions, brought religious dances to their deities -- that became syncretized among themselves and with those of Catholicism -- and dances that were mainly for enjoyment.

Towards the end of the 19th century, the existence of popular genres uniting elements brought by Spanish and African immigrants and their offspring was already evident. This was the case of the rumba and the son, much in force today and extended throughout the country with many local modalities.

Cuban traditional dances are very important for our cultural identity, since some of their elements characterize our people. As did other expressions in traditional culture, they acquired a collective nature when created, assimilated and transmitted as a way of satisfying expressive interests with various social meanings.

The present research completes studies on the various traditional dance genres in Cuba carried out by some institutions in an isolated and individual form. Their historical nature and regional demarcations were identified and, thus, the value of each of them could be appraised. A characterization of dance groups was also made, considering steps, movements, positions, formations and choreography in general; also, the ethnic background, the costumes and props used in the various dances, according to regional variations, were considered. This was done by grouping all existing corporal expressions on the basis of three elements: their motivation, the form they take and their ethnic background.

The information in the maps is a result of the analysis of field work data, obtained through questionnaires answered by persons who knew about one or more dance expressions, as well as by a review of the literature on the topic.

As in other Latin American countries, zapateado underwent changes in Cuba that were the origin of its variations. The morphological analyses of these dances show analogies with those in the Iberian Peninsula, reaffirming an indisputable Spanish origin.

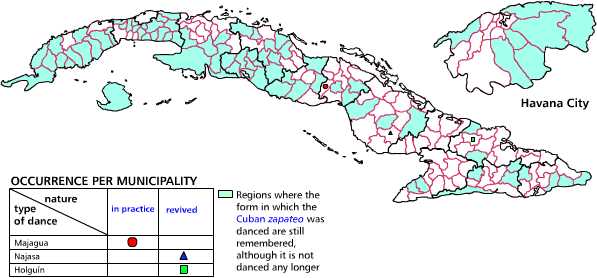

Cuban zapateo reached its climax on the second half of the 19th century and kept an important position until the first quarter of the following century. It is still remembered in most of the country. Of the three modalities under study -- Majagua, Najasa and Holguin -- only the first one is still in force, in peasant celebrations in Ciego de Avila province.

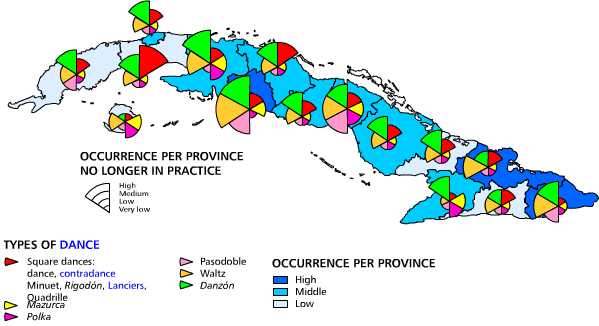

It is worthwhile to note that when this research was, made many persons still remembered how to dance zapateo and square dances. These dances entered Cuba from France and Spain at the end of the 18th century and extended throughout the country in the following century.

These dances at the beginning were only performed by high and middle classes in Cuban society, but left the dance halls and reached the larger population. This gave them new modalities and contributed to keep them alive for more than a century, mostly linked to the traditional celebrations of the Cuban people. Some of these expressions form part of traditional culture and are included under the name of danzas de salon, most of which have disappeared.

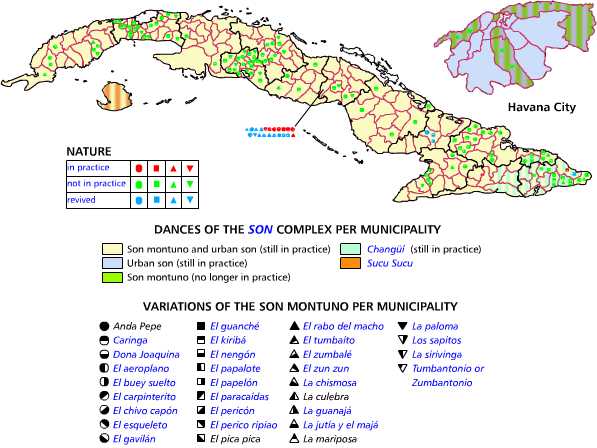

The son complex includes the son montuno dances, found throughout the territory, the changui in some municipalities to the east of the island, and the sucu-sucu, in the municipality presently known as the Isle of Youth.

Data on variations of son montuno that have already disappeared were obtained during this research.

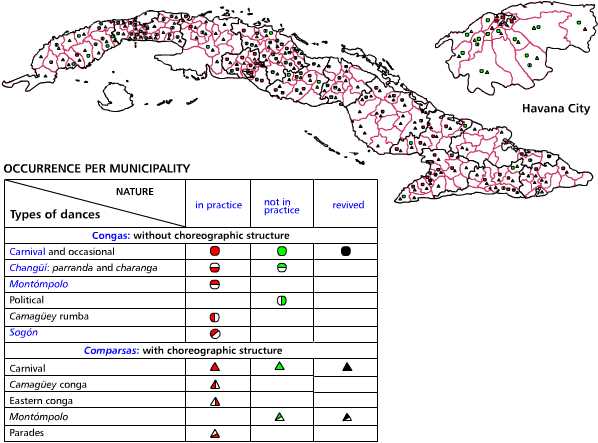

Congas and comparsas are dance forms characterized by processions and parades accompanied by music and songs. They are both very extended and take different names according to the locality. Congas -- characterized by a lack of choreographic structure -- are danced in the Carnivals in the western and central parts of the country. Political congas and the Camaguey rumba, the changuis in charangas (to the west) and parrandas (to the center), and the montompolo in Santiago de Cuba present similar characteristics and can thus be included in this group.

Artistic comparsas in the central and western parts of the country, the paseos in the eastern part of the country, the Camaguey and Oriente congas, and the montompolos in Guantanamo and Holguin are included in these comparsas that do have a choreography. Most of these dance expressions are still in force.

These dances were also closely linked to other celebrations that had nothing to do with the Carnivals, such as those for the patron saints and work celebrations, where verbenas and fairs were held, with congas and comparsas representing the various neighborhoods.

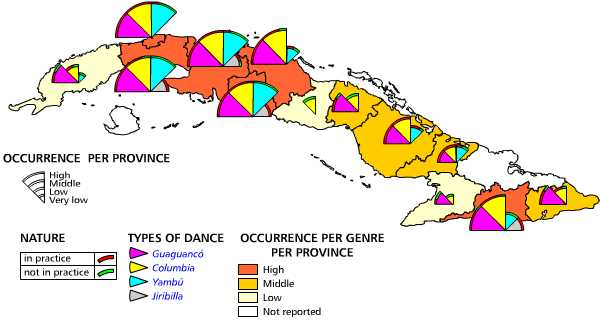

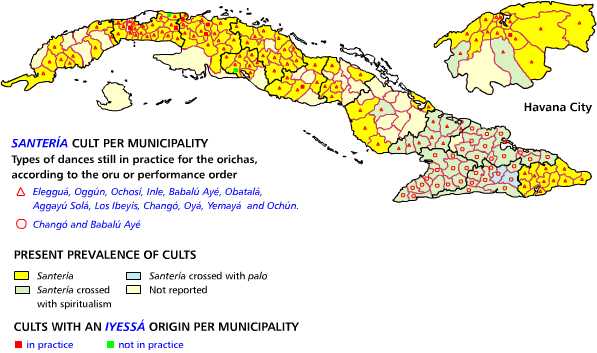

The rumba complex has several dances: yambu, guaguanco and columbia. Only guaguanco and columbia are danced today, together with the jiribilla, a variation of columbia. They are most frequently found in Havana, Matanzas and Villa Clara. Guaguanco and columbia are the dance forms of this group most frequently danced in Cuba. They have a wide spectrum of modalities and styles formed by an enormous number of steps and mime movements, derived from the motivations and ways of dancing to the orichas and intimately linked to their stories and traditions. The dances to the orichas -- Eleggua, Oggun, Ochosi, Inle, Babalu Aye, Obatala, Aggayu Sola, Ibeyis, Chango, Yemaya and Ochun -- prevail in the western part of the country, but are very extended throughout the nation, with variations in performance and other element between the Western and the Eastern regions.

In the Eastern region, dances do not follow a strict order; the most important ones are those devoted to Saint Lazarus (Babalu Aye) and Saint Barbara (Chango).

There is also the orille -- a dance in circles, characteristic of the cordon spiritualism -- and dances brought about by the merging of Santeria with Palo Monte. This last one is to be found in two municipalities in Santiago de Cuba. The names of some traditional groups and cabildos, still in force, also appear in this study.

The dances of Iyesa rites are very similar to those in Santeria. Although they were performed in several provinces in the past and present centuries, today they can only found in Matanzas and Sancti Spiritus.

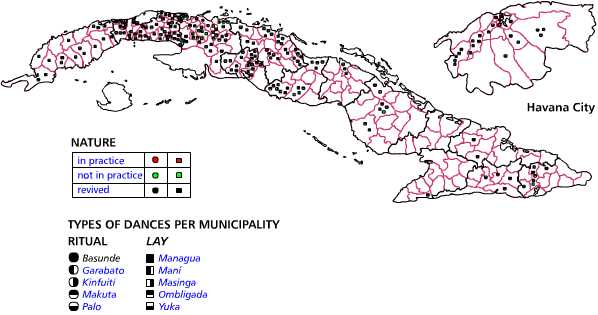

Dances having to do with Palo Monte celebrations and rites -- of a Bantu origin -- are found mainly in the western and central areas, although they are also found in some municipalities in the provinces of Santiago de Cuba, Holguin and Guantanamo, usually incorporating Santeria elements. Religiousity is very important in these expressions. The dances called Palo, kinfuiti, makuta, garabato and basunde, as well as others devoted to the cult of various deities or forces of Nature, have ritual connotations. There are also dances that seem to be only for enjoyment, but have possible religious origins. Yuka, mani, ombligada, masinga and managua are among them. The dance to the yuka drum was most significant and was recently revived in the province of Pinar del Rio.

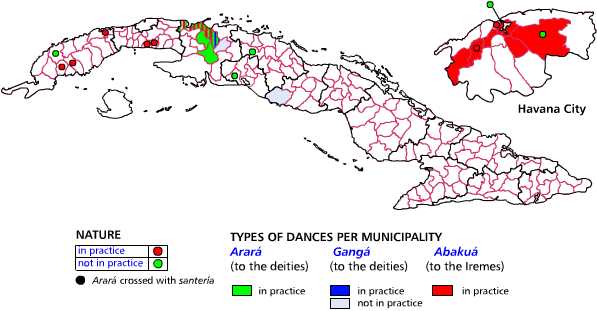

Other dances with an African origin deserve mention; even though the territories in which they are performed are much smaller, they form part of the dance traditions in the country. Arará dances in the western and central provinces, mainly Matanzas and Cienfuegos, are among them. In Pinar del Rio, Havana City, Havana and Villa Clara there are also elements characteristic of these cults, but syncretized with Santeria. These dance expressions maintain their most unadulterated form in the municipalities of Perico, Jovellanos, Cardenas, Agramonte and Matanzas in the province of Matanzas.

Each of its deities, called foddun, has its own very distinctive dances in which mimetic elements prevail. The psychological traits of these foddun are very similar to those in Santeria, while their main differences are to be found in the steps and movements.

Male secret societies called abakua have their distinctive dances; masked beings -- called iremes but popularly known as diablitos (little devils) -- take part in all their ceremonies. These dance expressions are only found today in Havana City and Matanzas, where these societies are located.

Even though dances of Ganga rites were found in Matanzas province at the turn of the century, today they only exist in one of its municipalities: Perico. Just as in Santeria, each deity has its distinctive dances according to its traditions.

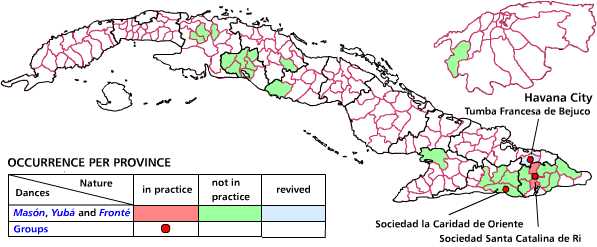

The migration to Cuba of French settlers from Haiti together with their slaves, as a consequence of the Revolution in that country, favored the creation of mutual help societies called Tumba francesa, that today exist only in Santiago de Cuba and Guantanamo. Their dances, called fronte, yuka, and mazun, have the style of French contredanses and are still performed today by Cubans of Haitian descent in the above mentioned provinces and, as a result of a cultural revival, in the town of Bejuco, in the province of Holguin.

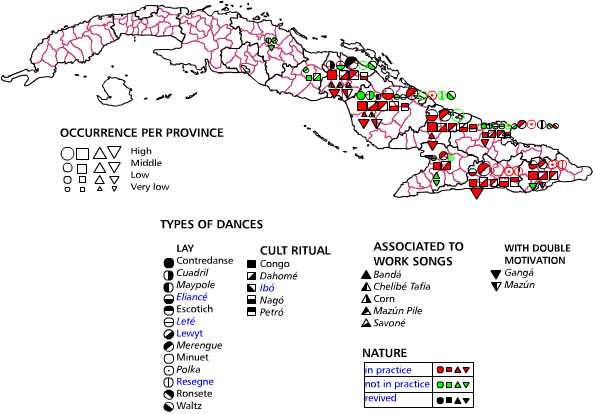

The Haitians who arrived in Cuba in the 20th century settled mainly in the eastern part of the country (Ciego de Avila, Camaguey, Las Tunas, Holguin, Granma, Santiago de Cuba and Guantanamo) and in some municipalities in Villa Clara and Sancti Spiritus. Their dances, still performed by traditional groups of Haitians and their offspring, may be religious or lay. Their lay dances are mostly work songs, while some other dances have a double character since they are used in religious or lay situations. The Bande Rara or Gaga, touring during Holy Week the sugar mill bateyes where Haitians and people of Haitian descent live in Ciego de Avila, Camaguey, Las Tunas and Santiago de Cuba, also deserve mention.

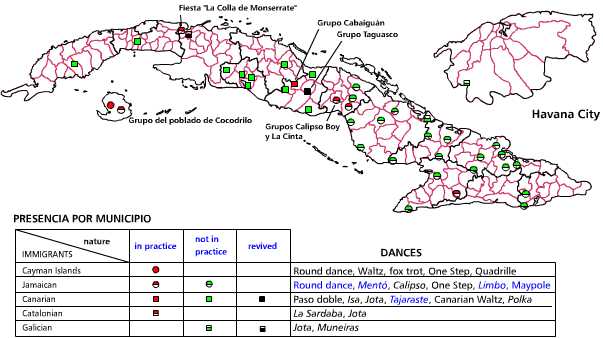

Immigrants from Canary Islands that settled mostly in the western and central part of the country (Pinar del Rio, Havana, Cienfuegos, Villa Clara and Sancti Spiritus) maintain their dance traditions only in some localities in Sancti Spiritus province.

The influence of Galician and Catalonian dances is evident in some celebrations called Colla de Sant Mus and Colla de Monserrat held in Havana City and Matanzas.

The presence of Jamaican immigrants is strong in some municipalities in the provinces of Ciego de Avila, Camaguey, Las Tunas, Santiago de Cuba, Holguin and Guantanamo, as well as in the municipality of Marianao in Havana City. In the Special Municipality of Isle of Youth, immigrants from Cayman Islands and their offspring perform their own dances and play their own music, together with the local sucu-sucu. Although people of Jamaican descent are to be found in the above mentioned provinces, dances of that origin are only to be found in the municipality of Baragua in Ciego de Avila province.

Many of the forms of dance we have mentioned are still found in some municipalities and provinces in the country; others, in many cases with historical roots, have been revived by groups of amateur and professional musicians, that are thus contributing to the wealth of cultural expressions in many localities in the country.

Lic. Caridad B. Santos Gracia

Maps

-

Zapateo

-

Hall dances

-

Son complex

-

Rumba complex

-

Congas and comparsas

-

Dances with lucumi (santeria) and iyessa origin

-

Dances with congo origin

-

Dances with an arara, ganga and carabali origin

-

Tumba francesa dances

-

Dances of the haitian immigrants. 20th century

-

Dances of spanish and west indian immigrants

-

Revivals and art projects

Videos

- Traditional popular music «

- Traditional dances

- » Oral traditions