The study of the ethnic components which gave origin to the contemporary Cuban nation is a necessary reference point for assessing the significance and reach of the present Atlas. Since colonial times, the main expressions of Cuban material and spiritual culture were intimately connected to the historic process of settlement, due to the complex links among the original ethnic components. These components were vital to the formation of the national ethos and its present consolidation.

Most of the research on the Cuban population has been conceived from a perspective principally demographic in its global vision, with isolated references to ethnic components, but with repeated confusion between ethnic and racial traits.

The study of the ethnic composition encompasses the synchronic and diachronic (historical, geographical and demographic) focus on aboriginal, Hispanic, African, Chinese-Philippine and West Indian settlement; as well as settlement from other places in the Americas, Europe and Asia, and also the most important of them all: Cuban settlement, that is, the human base that is today the main ethnic component of the nation.

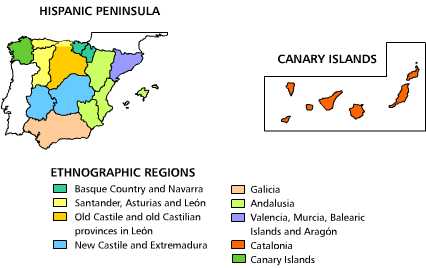

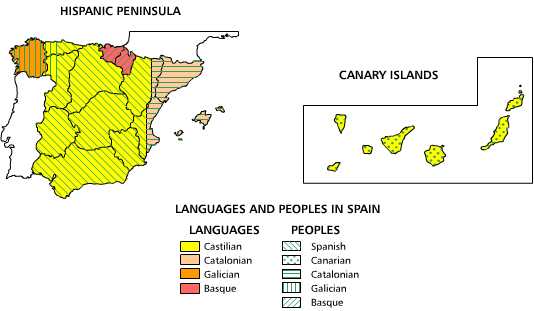

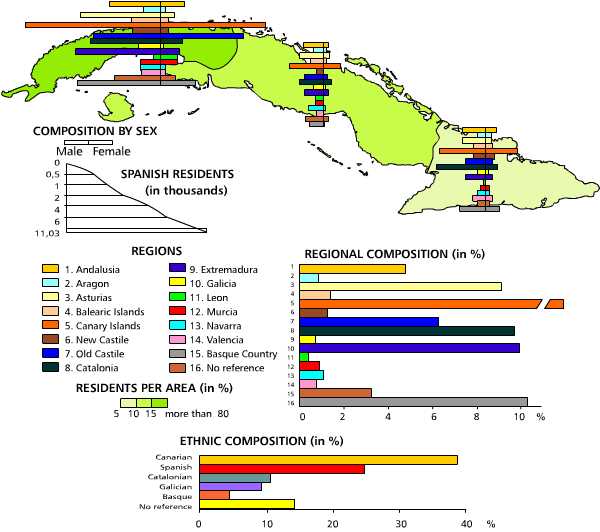

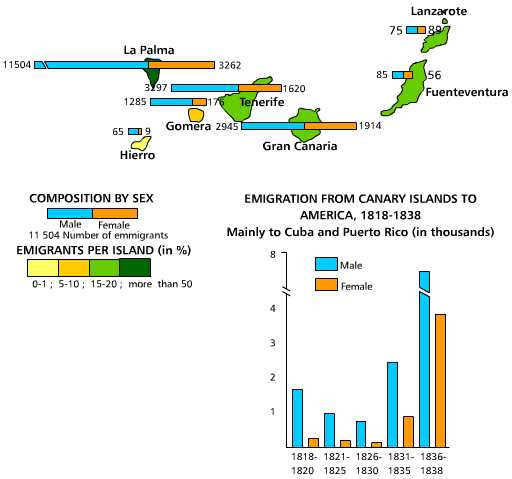

As to Hispanic components, in a geographical and meta-ethnical sense, that is, in reference to peninsular and insular Spain and the main peoples inhabiting it, the Spanish component, apart from its regional particular traits, prevails in and historically occupies the northern, central and southern areas in the regions of Asturias, Castile (Old and New), Leon, Extremadura, Aragon, Murcia, and part of Valencia and Navarra. Catalonians populate the northeastern area, in the regions of Catalonia, most of Valencia, the Balearic Islands and a small group in Aragon. Galicians live in the northwestern area, most of them in the historical region of Galicia and other smaller groups in areas neighboring Asturias and Leon. The Basque live to the north, west of the Pyrenees, in the territory of the present Basque provinces of Alava, Guipuzcua and Vizcaya, as well as in most of Navarra and part of the South of France. The Canarians, whose ethno-genesis has been the result of complex migratory processes, with multiple cultural influences from the North of Africa and Mediterranean Europe, live in the seven larger islands in the northwestern part of the African continent (Hierro, La Palma, Gomera, Tenerife, Grand Canary, Fuerteventura, and Lanzarote).

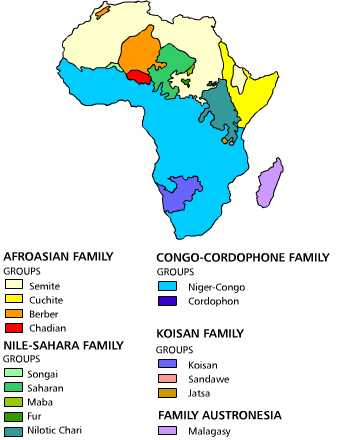

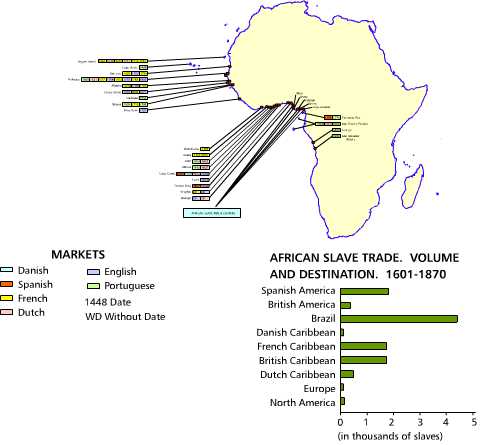

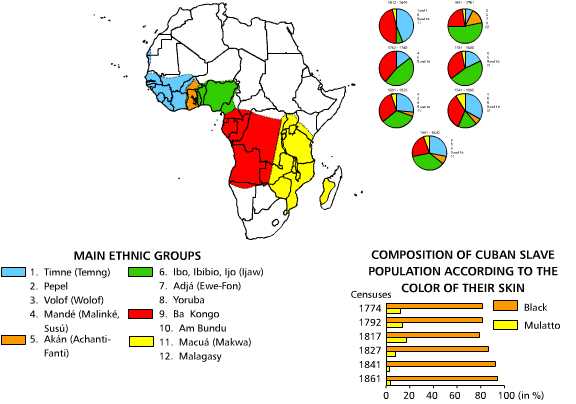

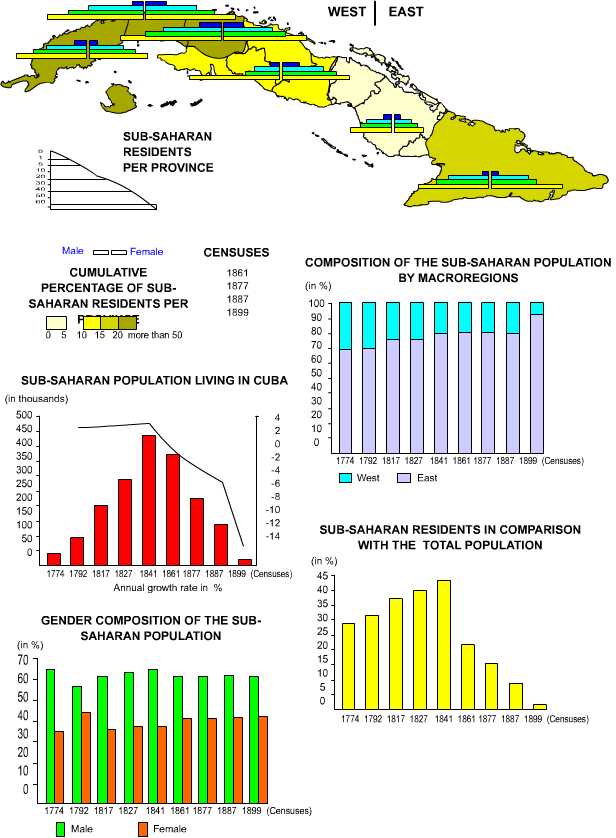

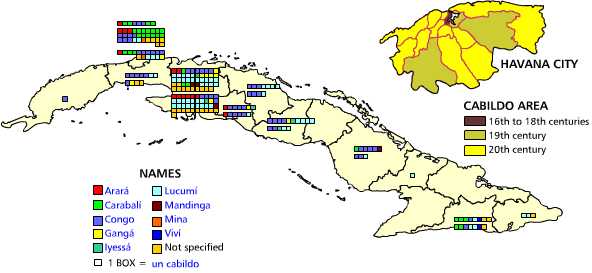

As to African components, we refer to the human groups brought from the sub-Saharan West Africa during the slave trade. They belong to many ethnic groups, linguistically linked to the Nigero-cordophone family, that in Cuba are known by various meta-ethnic names (Arara, Carabali, Congo, Ganga, Lucumi, Mandinga, Mina, and others), having to do with the toponymy and hydronymy of the places they lived, or were captured, concentrated and sold. This, in turn, encompasses several ethnonymies and ethnic denominations.

As to Chinese-Philippine components, we refer to peoples from the southern area of continental China and immigrants brought from the Philippines, although the latter came in lesser quantities.

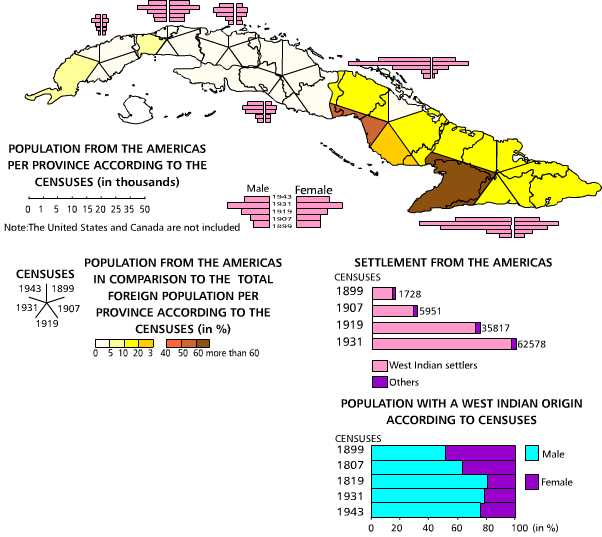

The great majority of the West Indians immigrants came from Haiti and Jamaica.

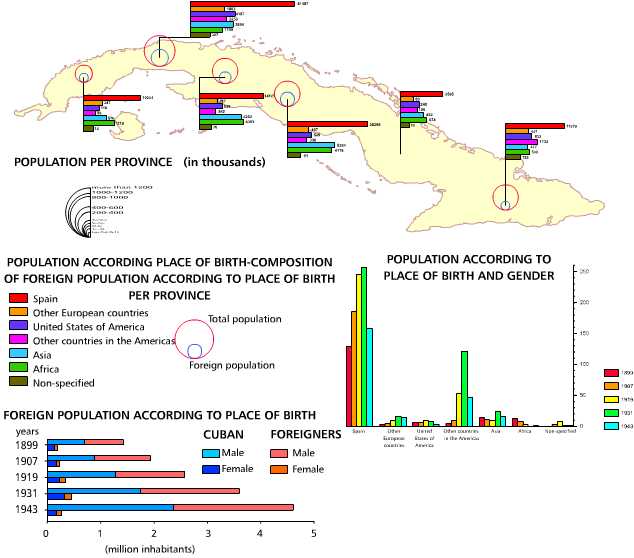

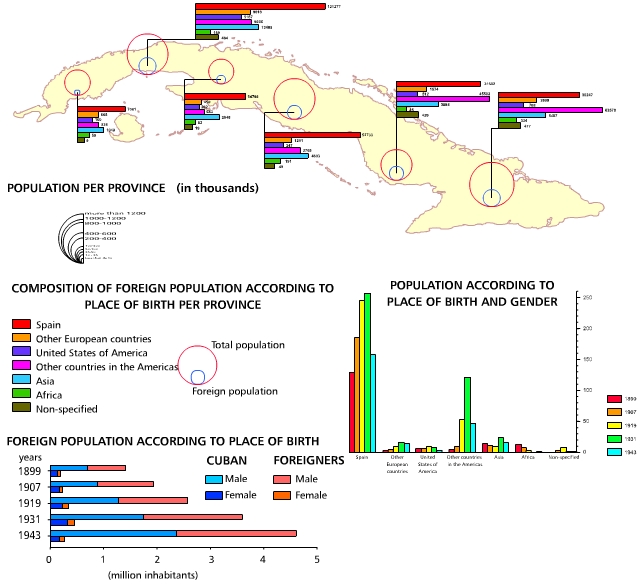

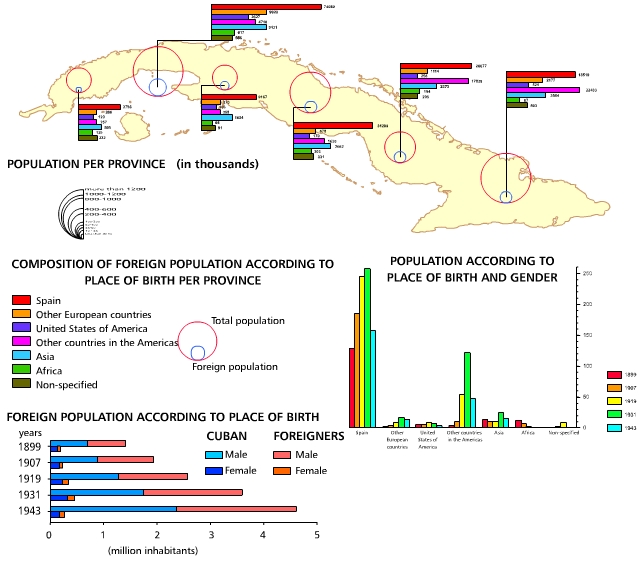

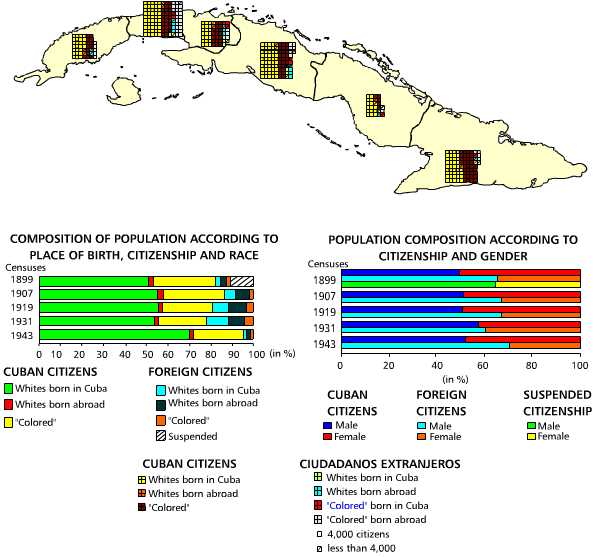

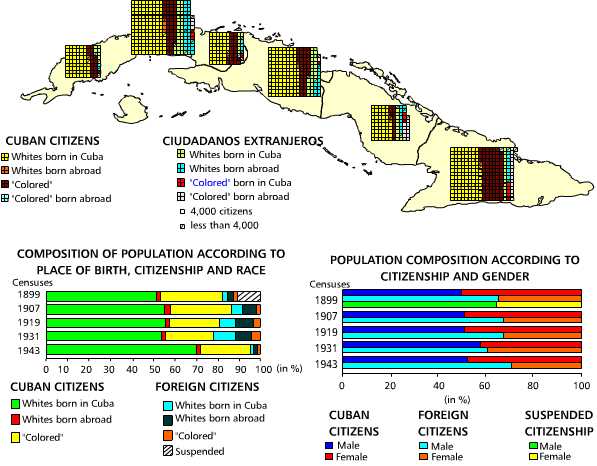

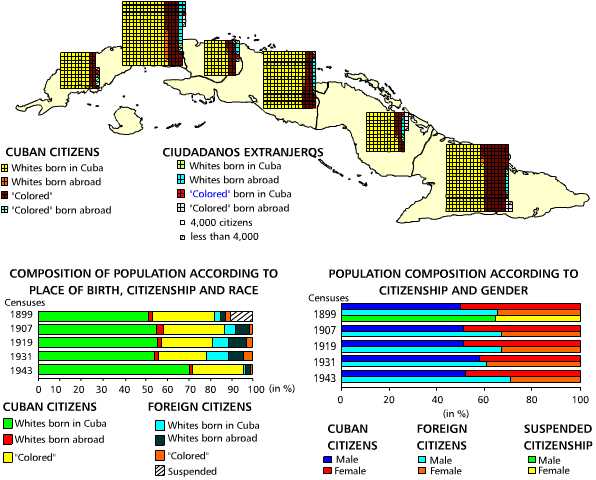

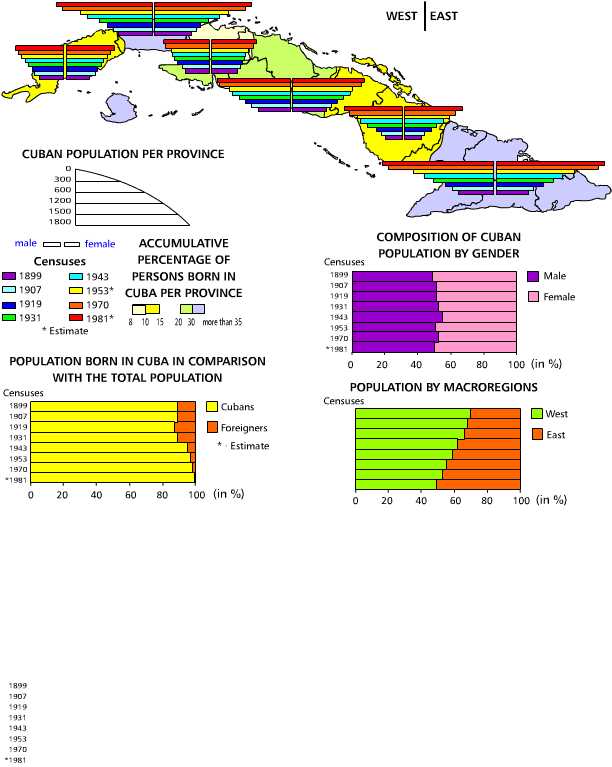

The quantitative-qualitative criteria of the various censuses included in the Atlas are one of the ways to assess the demographic significance of each ethnic component and, thus, its social and cultural importance, as well as to identify the main Cuban ethnic groups (more than 98 per cent of all the present population living in Cuba) from the small ethnic groups representing other peoples.

Therefore, small ethnic groups (a small part of a larger ethnic group living in a territory, inhabited by one or more quantitatively larger ethnic groups and forming a stable ethno-social body with a governmental and/or state apparatus) must be distinguished from ethnic minorities (ethnic groups living totally or almost totally in territories historically belonging to them, together with one or more quantitatively larger ethnic groups within the scope of a government and/or state). In other contexts, these concepts are defined differently.

Cuba has no ethnic minorities. Instead it has ethnic groups or individual representatives of other ethnic groups living in the country as permanent residents, in small communities or in households. Individually, none of them reach today one per cent of the population as a whole. The groups of Basque, Canarian, Catalonian, Chinese, Galician, Haitian, Jamaican, Japanese, Spanish, and others have the same civil and labor rights of the rest of the population. Their accelerated blend with the local inhabitants has positively influenced two types of narrowly inter-connected ethnic processes:

- Firstly, the degree of consolidation of the national ethnos of the Cuban people increases, since it not only grows in itself (by natural growth), but incorporates for itself those born from other peoples and, above all, their offspring, apart from the migratory exodus.

- Secondly, at the same time, the process of natural assimilation of small ethnic groups and their representatives to the national ethnos is accelerated from the first or second generations, according to the degree and intensity of the linguistic, cultural (and even matrimonial) proximity or distance of the group and its individuals in relation to the Cuban national ethnos.

An important source for the reconstruction of Cuban ethnic history is the set of relatively reliable censuses extending from the colonial times (1774) to 1970. These document the birth place of people living in Cuba. Unfortunately, the 1981 census did not include place of birth in its national survey, thus interrupting research on this topic. In contrast with race and citizenship indicators, place of birth tends to be a better reflection of the diverse regional ethnic composition from which individuals originate or to which they belong, since the narrow notion of race is limited to the color of the skin, and citizenship merely indicates the legal, and not the ethnic, status.

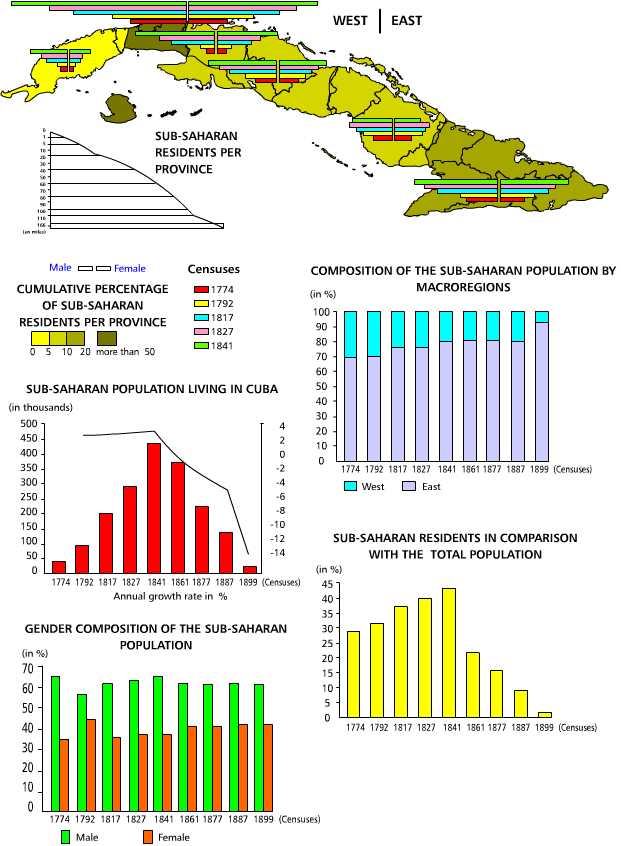

However, place of birth is a global data that does not clearly show ethnic composition, because Spanish and sub-Saharan African immigration -- the most important and stable migratory waves after aboriginal ethnocide -- was multi-ethnic with origins in vast territories; at least, these data allow for the compilation of some operative figures on the total population of the country in each of the censuses, which can be used in comparative analyses with other research sources.

Parish archives are another source that may offer answers to issues in population ethno-history. Although little studied, they are very useful in the study of colonial times. Their sample study has allowed a characterization of the areas and towns with origins in Hispanic and African immigration, as well as other places in the Americas, Europe and Asia. This makes it possible to measure, from the first years of the study, the great significance of the population born in Cuba, whatever the place of origin of their parents.

As to the aboriginal population, Indians were entered into several parish records -- mostly in Jiguani, Bayamo, El Caney, Baracoa, and Holguin -- until well into the 19th century, a period in which, according to most historians, they had already disappeared.

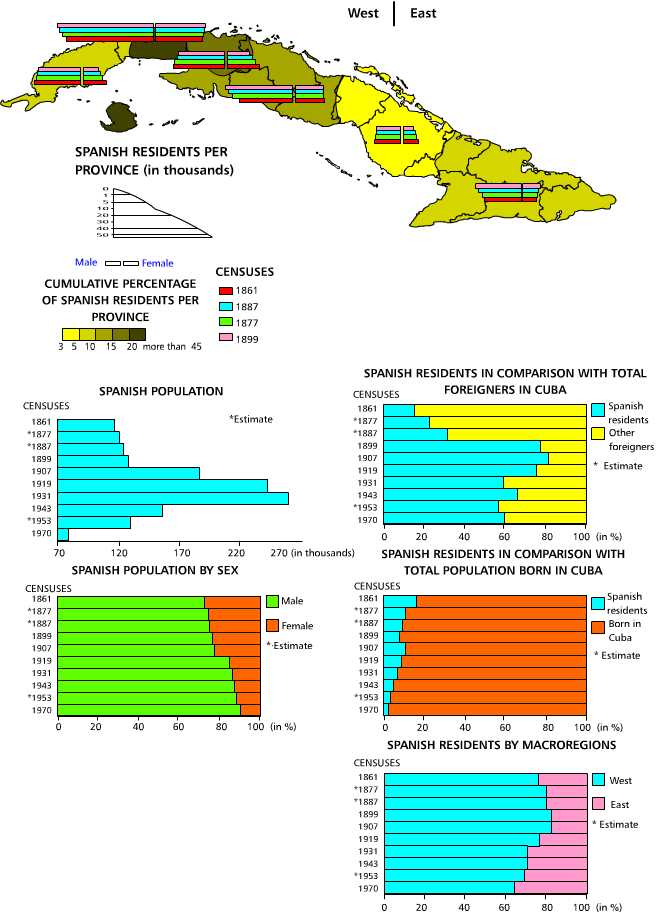

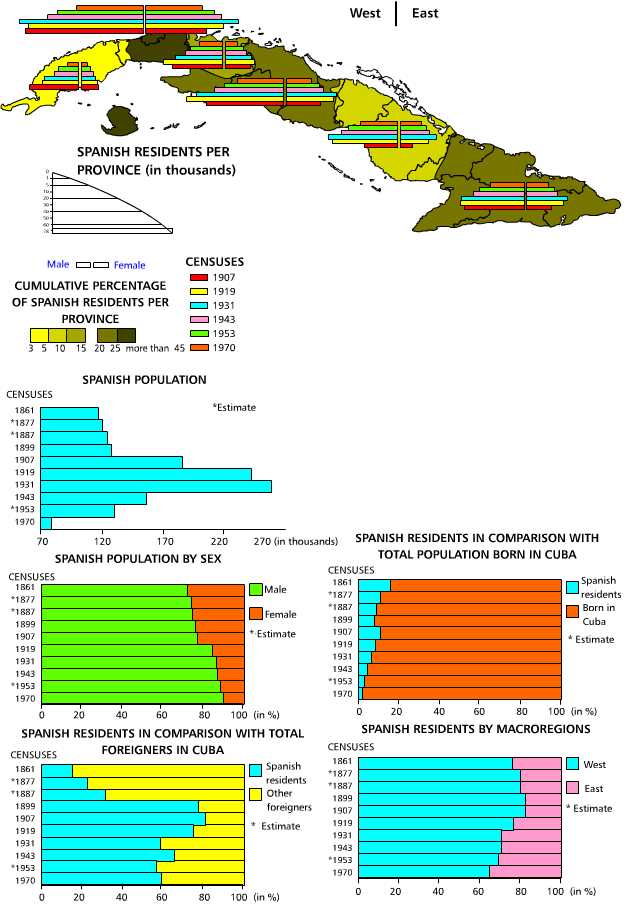

When considering the Hispanic population, the information on place of origin included in the parish records is very heterogeneous, since they used as a basis villages, regions, towns, cities, principalities and archbishopries. This makes it necessary to collate a large volume of data to verify historic, ethnographic and linguistic regions so as to identify the ethnic origin of residents from their place of birth. Also, the correlation of the data in the records with that of the census and other related work allows an assessment of qualitative and quantitative changes in external migratory processes. It allows too to ascertain that the largest demographic significance of Hispanic immigration, in itself and as a total of Cuban population, did not take place in colonial times, but in the three first decades of the 20th century.

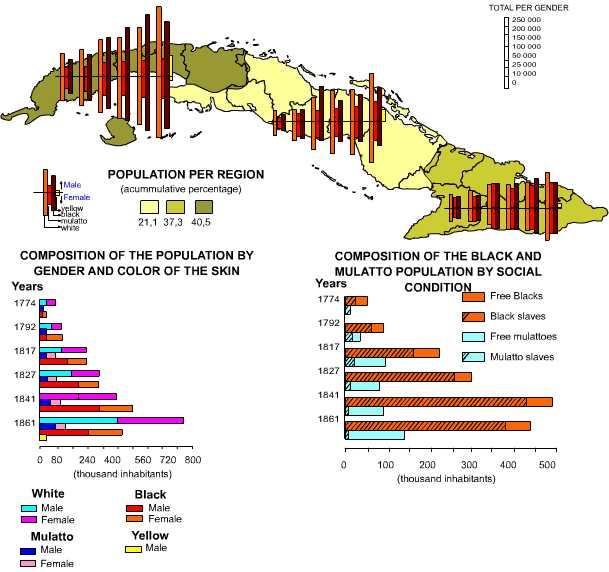

As to the forced migration from sub-Saharan West Africa, parish records corroborate that the immense majority of the population considered black in the censuses (more than 90 per cent) were slaves and born in Africa -- thus the generic or meta-ethnic denomination of the individual regularly appears. These records also corroborate that, on the contrary, the immense majority of the population considered mulatto in the censuses was free and born in Cuba; this is also confirmed in the gender composition of the censuses according to the color of the skin, whereby the number of males in the population registered as white and black is larger than that in the mulatto population, more balanced as to male and female. The presence of Chinese, West Indians, Americans and others can be identified through the existing census data, comparing it with results from other recent demographic and ethnologic research and various statistical estimates.

At the same time, the Cuban population is the historic result and a new ethnic synthesis of former types of settlement. Even when census information allows to reconstruct settlements from the middle of the 19th century (1861), the data from various parish records makes it possible to measure its high statistical significance -- first as Creole or endogenous population -- from a stage before the first census made in Cuba (1774) to the process of formation of the Cuban nation.

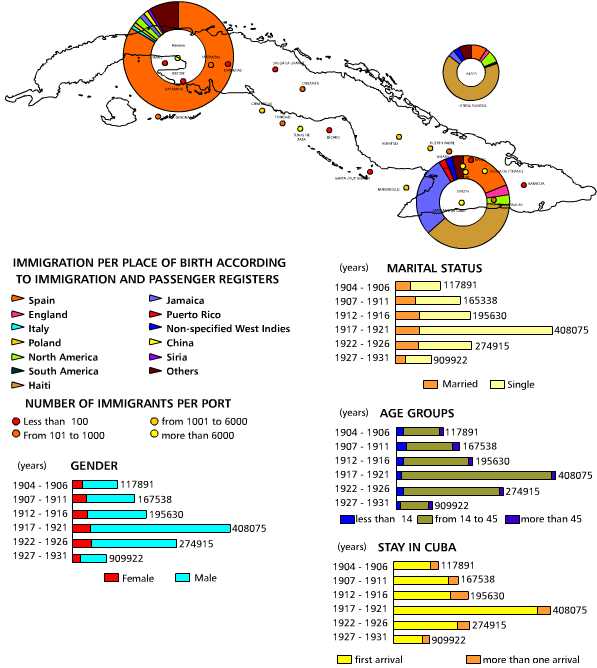

During the neocolonial era, statistical information that may have served as the basis for studies on immigration was characterized by its fragmentation and dispersion. Thus, for example, while the Ministry of the Treasury collected all the data on migration, the Ministry of the Interior was in charge of the Registry and the Ministry of Health was in charge of the death records. At a national level, no institution guided or analyzed these activities as a whole.

Population Censuses, created from 1907 onwards for electoral purposes, present limitations that restrict the possibility of comparing and assessing the dynamics of any phenomenon that took place between two census periods even when their organization and contents were, in most cases, based on the pattern set by the 1899 Census made by US military authorities during the intervention. Changes in the parameters that had been set, the deletion or generalization of various indicators in its statistical tables, and even difficulties inherent in the processing and publishing of some of them make comparisons difficult. In spite of these inconveniences, censuses are required reference to learn about the demographic significance of various ethnic components, their territorial distribution and their degree of concentration or dispersion in the national territory.

Another important source are the statistical series that, from 1902 onwards, were compiled by the Ministry of the Treasury on the movement of immigrants and passengers. These series offer a more detailed view of the characteristics of this immigration, even when some inexactness and omissions between the various periods can be detected.

All this allows for a new ethno-historic interpretation of the settlement of Cuba from its original ethnic components to the contemporary Cuban population. The interaction of linguistic, cultural, psychological, biological, spacial and temporal factors conditioning the formation and development of ethnicity in every historically established human group, with their common traits and quantitative dependence, is intimately linked to the creation, transmission and transformation of cultural activities, objects and values. All these topics are found in the Ethnographic Atlas.

Because this historic process developed for more than half a millennium, the Cuban people, as a contemporary society formed by more than eleven million persons, is a mono-ethnic and multi-racial nation. This fact, uncommon in the ethno-genesis of many peoples of Africa, Asia and Europe, regularly emerges in the new peoples of the Americas, and should be highly considered.

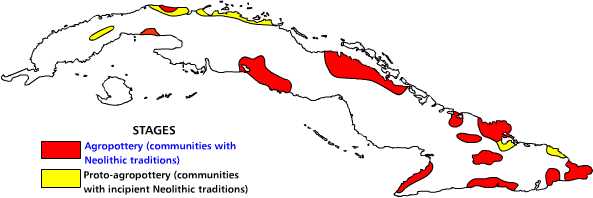

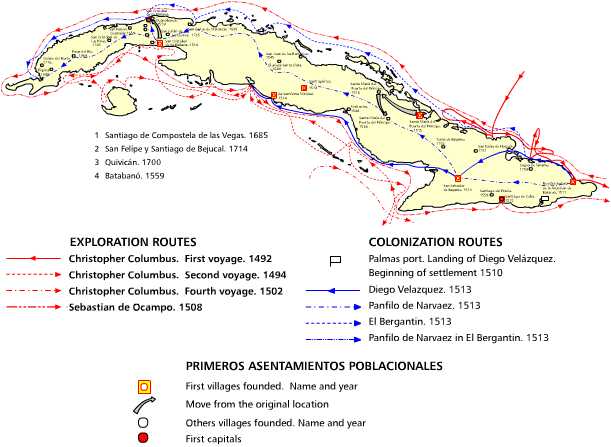

From an ethnic point of view, the violent impact of the Hispanic conquest on the island Arawak population, established in the archipelago for millennia, reduced the estimated global amount of inhabitants from 112,000 in 1510 to only 3,900 in 1555, that is, a decline to 3.48 per cent of the initial population in less than half a century. Thus, this ethnic component did not play a significant demographic role. From the start, Amerindians were found in small groups in Guanabacoa in the present Havana province, and in Jiguani and El Cobre in the present Granma and Santiago de Cuba provinces. They were also scattered in isolated places, such as the mountains in Guantanamo, where Cubans of Arawak ascent can still be found, already blended with the local population.

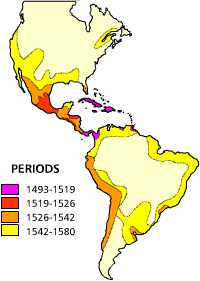

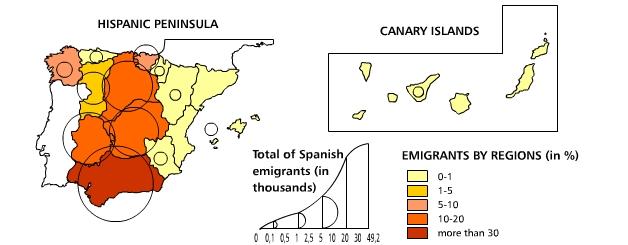

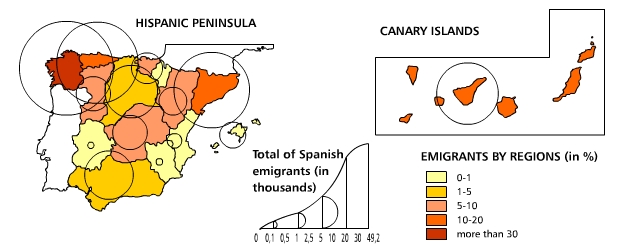

Migrations from the south of Spain and its islands (mainly from Andalucia and the Canary Islands) during the 16th to the 18th centuries, as well as the forced migrations from the western part of sub-Saharan Africa (specifically the Bantu speaking peoples and, later, the Yoruba, whose massive entrance reached its climax during the first half of the 19th century, after the "legal" ban on the slave trade), were very important in the formation of the Cuban population. Both multi-ethnic conglomerates, those from Spain (Canarians, Catalonians, Spanish, Galicians, and Basque) and from the sub-Saharan West Africa (Achanti, Bacongo, Bambara, Fulbe, Ibibio, Ibo, Malinke, Yoruba, and many others), blended so intimately, individually (Hispanics and Africans) and among each other (Hispano-Africans) that an endogenous population that did not depend only on foreign migration, but on its own reproductive capacity, emerged from the 16th century on. Spanish and Canarians, together with Bacongo-Ambundo, Ibo-Ibibio, Wolof, Achanti-Fanti, and Ewe-Fon components, played a significant primary role in the formation of a non-Arawak genetic and cultural substrate that became the bearers of demographic development. The massive entrance at a later date of Galicians, Catalonians, Yoruba, Malinke, among others, widened the Hispanic and sub-Saharan spectrum of the population already existing in Cuba.

From the last decade in the 18th to the first years of the 19th century there was an important flow of French and French-Haitian immigrants (a mixed population born in Haiti with both African and French traits) due to the revolutionary uprising in Haiti. They settled mostly to the southeastern part of the island and had a favorable impact on its social, economic and cultural development.

From the middle of the 19th century, several Asian components were incorporated into the ethnic kaleidoscope of the country. Most of them came from the south of China and the Philippines as indentured labor and, later, several thousand of Chinese from California settled in the urban areas of western Cuba.

The co-existence of these ethnic components of various origins, characterized by a high index of males and their obvious matrimonial relationship with women born in Cuba, who were the offspring, in turn, of the first immigrants, generated processes of transmission at intra-generational and inter-generational cultural levels. These were conditioned by the active role of the endogenous mothers and grandmothers (also born and reared in a new cultural, spacial and temporal environment) in the raising of their children and grandchildren, in comparison with Hispanic, African, Asian or West Indian immigrants, to mention only the most salient ones.

Ethnic traits synthesizing Hispanic and/or African or other traits (according to the place of settlement and the social group to which they belong), began to appear in the new generations born in Cuba from the 16th century on. They encompassed the most diverse areas of life. New ethnic traits developed simultaneously, conditioned by space and temporal contexts that were not yet national, but that during the colonial times -- the formative stage of the Cuban people -- were limited to the area in which the population lived. During this period, internal migrations did not play a role as important in demographic dynamics as migrations from abroad did and, specifically, as that of the natural growth of the population, that had reached an accelerated pace.

Traits such as a sense of belonging to a territory (locality or region); the generalized use of Spanish with its peculiar speech and lexical nuances (enriched with many toponyms, hydronyms and Arawak and non-Arawak terms, as well as with some sub-Saharan terms of a more limited reach); cultural and psychological traits conditioned by economic and productive activities, belonging to a given social class and deeply linked with the permanent process of information transmission in social, family and interpersonal levels; all these had a more significant function than biological and anthropological differences among the individuals in the formation of an ethnic human being distinct from its historical ancestors.

The formation of an ethnic self-awareness that, in its development, merged in the Cuban context with a national awareness that identified this human group, meanwhile differentiating it from others, reached its climax in the anticolonial struggle for independence (1868-1898). This struggle, with its own distinctive traits, was a historical result of a movement throughout the Americas.

The 20th century arrived in the midst of an economic and population crisis generated by the 1895-1898 war. As part of a new project of neocolonial dependence in the republican context, the doors were opened to massive immigration, mostly from Spain and the West Indies, in conditions as taxing as those in the previous century, especially for immigrants trying to make a living only as manpower. At the same time, the increasing investment of capital (mostly from the U. S.) and the resulting specialized family immigration contributed the finishing touches to the underdeveloped social and economic structure and its many negative implications centering around a permanent political, social and economic instability. In spite of all this, the quantitative demographic significance, as well as the qualitative significance of cultural issues in the Cuban population during the 20th century, have had a greater weight than the exogenous ethnic components. This has contributed to preserve an identity that, although undergoing changes with the times, did not disappear in the face of an open strategy of dissolution through migration during the neocolonial era, whether through foreigners coming to Cuba or Cubans leaving for other countries.

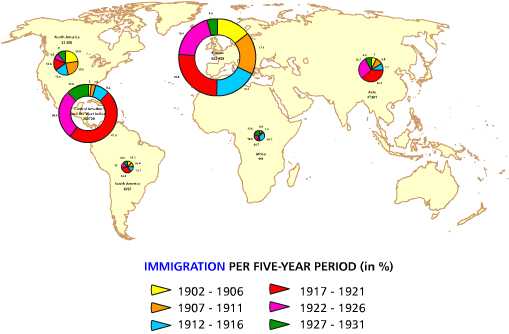

During the three first decades in the 20th century, Cuba received a strong migratory flow. About 1.2 million immigrants entered the country in those years with a decisive impact on the population growth and the social and economic development of the country. Through a creative and dynamic process, they brought elements that enriched national culture to a larger or lesser extent. Immigration became a key factor in the plans for economic reconstruction, drawn by the ruling class immediately after independence. Immigrants were considered a quick and effective solution to labor force problems, since in 1899 the country, destroyed by the war, had only 1,572,797 inhabitants. From that moment on until the beginning of the 1930s, their volume, composition and importance were conditioned by economic factors and determined by the processes of expansion or contraction in the sugar industry throughout this period.

Thus, while migratory laws in force during the first decade of the republic favored the arrival of white immigrants -- mostly from Spain and its islands -- limitations were abandoned that from 1913 onwards had banned the arrival of some nationalities considered "undesirable". This was caused by the expansion of the sugar industry during the First World War and the post war period. Thus, the "West Indian laborer" entered the national scene as cheap manpower required to guarantee the exhausting agricultural work of cane cutting and milling.

The process of deterioration and crisis of Cuban economy began in the 1920s. Its effect was immediately seen not so much in the immigration figures but in their composition and territorial distribution. For the first time, Haitians and Jamaicans reached annual figures higher than those of immigrants from other countries, since they became indispensable to an economic policy oriented towards reducing salaries and production costs.

Immigration started a clear decline from 1926 on. The 1929 world crisis and its impact on a dependent and underdeveloped economy such as Cuba′s, together with the U. S. customs policy and the protectionist Hawley-Smoot Act (that caused a steep decline of Cuba′s sugar market and placed the country at the brink of economic collapse), favored the outbreak of a revolutionary process and created unfavorable conditions for immigration. The deterioration of economy, as well as the decline in sugar production (with the resulting lengthening of the "dead time" and the growth of unemployment), were the cause of the 1933 act for the compulsory repatriation of foreigners, declaring them a burden for the State. Many Haitians were forced to return to their country. The fact that some had established a family in Cuba and that others had economic means to survive were ignored. The Work Nationalization Act, decreeing that 50 per cent of the workers or employees in every company had to be Cuban, contributed to this situation.

Both actions, intended to protect native workers, closed the door to an economic immigration that until then had been encouraged, but that in the future would find no employment in a country sunk in a serious social and economic crisis. After 1934 this crisis became permanent with the signature of the new Trade Reciprocity Treaty with the United States of America, as well as the adoption of the Costigan-Jones Act or Sugar Quota Act, that established the future maximum capacity of this industry.

During this stage, the Hispanic component maintained a stable and larger flow, favored by various factors. The similarity of habits, language, education and religion; the existence in Cuba of a powerful Spanish colony with important economic and political relationships; the fact that relatives, friends, acquaintances or simply people from the same region lived throughout the island, were coupled with a favorable set of immigration laws. On the other hand, the myth of the wealth and the opportunities existing in the Americas, together with the poverty and unemployment prevailing in some regions in Spain and circumstantial events such as the Moroccan war, encouraged immigration from Spain up to a point that Cuba became the country receiving more Hispanic immigrants in that period, second only to Argentina.

Haitians and Jamaicans, the second largest group, were concentrated in the sugar and coffee areas of the former provinces of Oriente and Camaguey. The fact that they were black, that they spoke different languages and had different habits, as well as the subhuman conditions to which they were submitted, made the characteristics of this type of 20th century immigration very different.

The situation of Jamaicans, although not enticing, was more favorable to that of the Haitians, since they had the protection of their Consulate, spoke English and had higher educational levels, including the mastery of several trades. To the contrary, from the moment Haitians were contracted in their country, they were the victims of every type of humiliation. Most were illiterate and Cubans did not understand their language. They were stacked in barracks, paid a miserable salary in tokens and notes, and compelled to hand in their meager savings to reimburse their trip. They had no protection at all and their status was similar to that of the 19th century Chinese coolies.

Other ethnic components arrived in Cuba in these 30 years of republican life. They also entered the Cuban melting pot, where they were mixed and disbanded in a single social ferment.

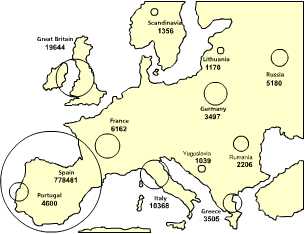

Important groups of English, Italian, Polish, French, Russian and Portuguese origin arrived in those years, together with Dutchmen, Lithuanians, Hungarians and Rumanians, among others, from a Europe that had suffered the upheavals of the First World War, and was full of fear and uncertainty at the triumph of the October Revolution, as well as the post war economic situation.

Chinese immigration continued to be the most significant from Asia, in spite of laws limiting Chinese entrance (under the racist and xenophobic argument that they brought with them the moral and physical flaws implicit in their race) in some periods. Some Syrian, Turks, Japanese, Palestinians, Hindus, and even Philippines arrived in these years.

The largest number of Latin Americans came from Mexico and Puerto Rico, together with some Dominicans and a small number of Central Americans.

Immigration from the United States was also stable, favored by mechanisms of economic and political domination imposed by that country, but contrary to the others, it was a white, skilled and familial immigration that remained isolated from the cultural environment as much as possible. Although most of the Americans came in the early years of the neocolonial republic, attracted by the various attempts at agricultural colonization in the former provinces of Camaguey, Oriente and in Isle of Pines, there have always been many U.S. citizens in Cuba, most of them living in Havana and other towns in the country, as well as in the places where they had invested their money.

When reference is made to the ethnic composition of the Cuban population, this should not be identified or misunderstood with racial composition, since the study of races and human types fundamentally encompasses the biological and anthropological characteristics of the individuals of a historically and culturally conditioned group context. The most recent studies on the relationship between race and ethnic traits confirm that differences between them are larger than similarities.

From the racial point of view, even when the Mongoloid race, represented by Amerindian natives, rapidly declined because they physically disappeared or were blended with other human races, the Mediterranean type of the Europoid race and the Negroid race from the Western sub-Saharan region tended to grow. They grew not only by themselves, but also in relative balance with the sexual composition of the blend among them, that is, in the mulatto population (Europoid-Negroid) or in other forms of miscegenation (Europoid-native or Negroid-native). In spite of the institutional or social and family racism existing in public social relations, statistics and parish records prove that things were different from a private point of view.

Ethnically and racially mixed marriages are found among all the human groups in Cuba. Meeting in a new environment contributed to a rupture in ethnic endogamy and conditioned the creation of new exogamic marriages simultaneously with several endogamic circles with a territorial character, as an essential norm of every ethos from its formative stages. These endogamic circles became stronger in settlements that were far from the coasts (for example, in the present towns of Sancti Spiritus, Camaguey and Holguin, where marriages between people born in Cuba fluctuated from three-fourths to eight-tenths, with the presence of a limited number of families that inter-crossed), and weaker in coastal towns like Havana and Santiago de Cuba, because their cosmopolitan nature and intense port activity generated an extended mercantile and human traffic.

If a racially mulatto population was the evident result of mixed marriages between Hispanics and Africans, in the most immediate and superficial sense of miscegenation, a similar mixture occurs with intra-European mixes (Spanish, Canarian, French, Italian, and others).

The population belonging to the Asian branch of the Mongoloid race, represented by Chinese coolies, Philippinos and by Chinese-Californian tradesmen, was almost exclusively male, which influenced their accelerated inter-racial and inter-cultural blend.

Instead of creating disconnected ethnic components, multi-racial traits inherent in the historical formation of the Cuban national ethos, encouraged the systemic formation of a concatenated set of unifying ethnic processes of various territorial scopes and chronological lengths.

Due to the forced Hispanic-native ethnic assimilation (which caused the near total physical disappearance of the aboriginals and contributed to the incorporation of various linguistic and cultural elements into the contemporary Cuban heritage), as well as to the Hispanic-African mixture or merging (the result and synthesis of various processes of inter-Hispanic and inter-African integration) a population emerged, born in the country, that tended to reproduce biologically and culturally for various generations at a more accelerated pace than external migrations and became not only independent from it, but was its most important ethnic component.

This conditioned a trend towards national ethnic consolidation that, in overall population indexes, is evidenced in gender composition as to the biological and cultural reproduction of the ethnos and, in the macro-regional location of the Cuban population, in the relatively stable balance of its geographic location after an accelerated process of urbanization that began towards the middle of the 19th century and the growth in internal migration.

External migrations of the Cuban population during the present century, conditioned by endogenous and exogenous factors, tended to generate processes of ethnic division in relation to the larger national ethnos. However, the 1.5 million of Cubans living in more than forty nations are also direct or referential bearers of diverse forms of national culture and are not only influenced by the language and culture of the countries where they live, but participate in them by contributing their own social and cultural characteristics.

Dr. Jesús Guanche Perez

Dr. Ana Julia Garcia Dally

Maps

-

Aboriginal population in cuba

-

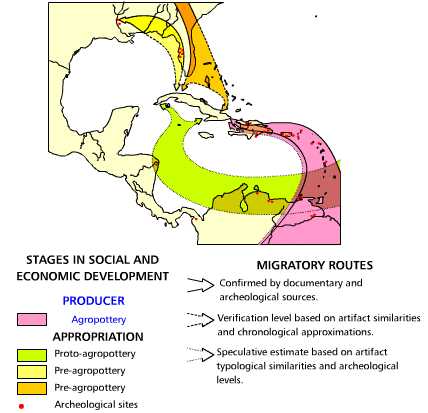

Distribution of communities with paleolithic and mesolithic (pre-agropottery) traditions

-

Distribution of communities with incipient neolithic (proto-agropottery) and neolithic (agropottery) traditions

-

Main exploration and colonization routes

-

Spanish territorial occupation in america

-

Historic and ethnographic regions in spain

-

Languages and peoples in spain

-

Spanish emigration to america. 1493-1600

-

Emigration from spain to cuba. 1885-1895

-

Chronological sample of the ethnic and regional composition of the spanish population during the colonial period, according to parish archives

-

Spanish settlement. 1861

-

Emigration from canary islands to cuba according to a commendatory sample. 1848-1898

-

Spanish population. 1861 1899

-

Spanish population. 1907-1970

-

African ethnolinguistic areas

-

Main markets of african slaves.1448-1800

-

Origin of the africans brought to cuba

-

Sub-saharan settlement. 1774-1841

-

Sub-saharan settlement. 1861-1899

-

Population by gender, color of the skin and social condition 1774-1861

-

Confraternities, cabildos and societies formed by

-

Immigrants per area of origin. 1902-1931

-

Main countries of origin. 1902-1931. Europe

-

Central america and the caribbean

-

Main immigration per port of entrance. 1902-1931

-

Ethnic composition of foreign residents. 1899

-

Ethnic composition of foreign residents. 1931

-

Ethnic composition of foreign residents. 1943

-

Citizenship and color of the skin. 1899

-

Citizenship and color of the skin. 1931

-

Citizenship and color of the skin. 1943

-

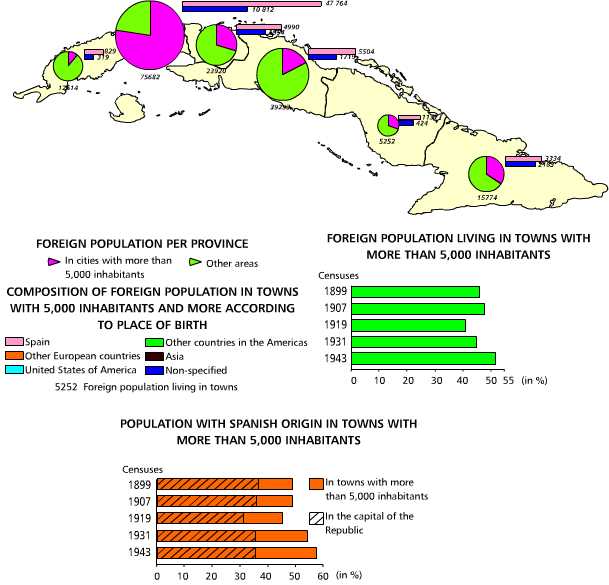

Distribution of foreign population. 1899

-

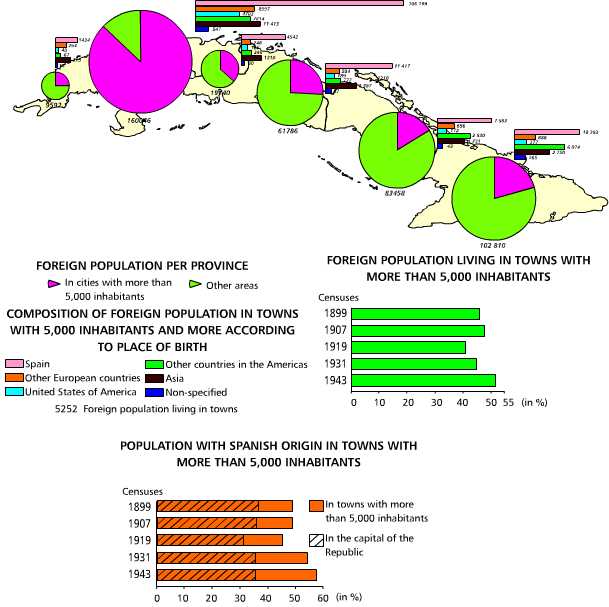

Distribution of foreign population. 1931

-

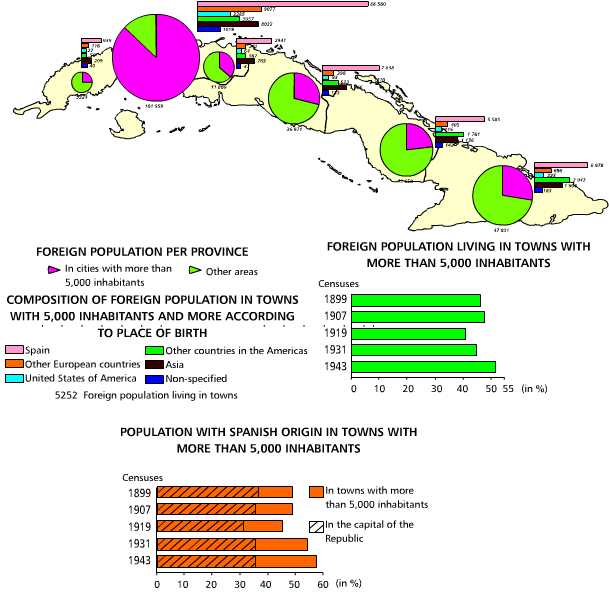

Distribution of foreign population. 1943

-

Settlement from the americas

-

Settlement of cuba. 1899-1981

Videos

- Introduction «

- Ethnic history

- » Rural settlements