Cuban contemporary forms of population and the establishment and development of rural settlements are the result of a long process that started with the conquest and colonization of the island at the beginning of the 16th Century. In contrast to what happened in other parts of the Americas, native townships in Cuba disappeared as their inhabitants were decimated. The foundation of seven villages by Diego Velazquez between 1511 and 1515 was the first step in the process of colonization and population. These villages were the first in an economic and demographic movement that was conditioned by various inner and outer motivations.

After the first moments of the conquest and colonization, the sharp decline in natives, the lack of gold deposits and new outer motivations, especially the campaigns for the conquests that were taking place in the continent, caused a rapid depopulation of Cuba a few years after the arrival of the Spanish settlers. The foundation of villages took a different form. Colonization and settling followed paths marked by the new economic activities in the island. The information presented in this Atlas intends to deepen our knowledge of this process and to highlight some of its regional characteristics.

This study is endowed with specific importance in the framework of the research into which it is included, since it may contribute to the analysis of the history, habits, traditions and culture of the rural population. The existence and preservation of various expressions of Traditional Popular Culture shows a marked relationship with the types of settlements. It is true that they are the result of specific social and economic conditions, but once established they become part and parcel of cultural heritage and impact directly on the social and cultural life of the population.

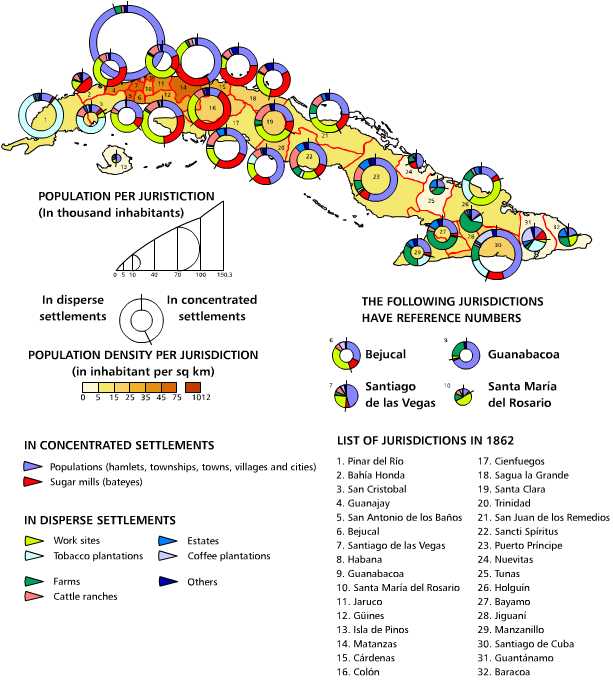

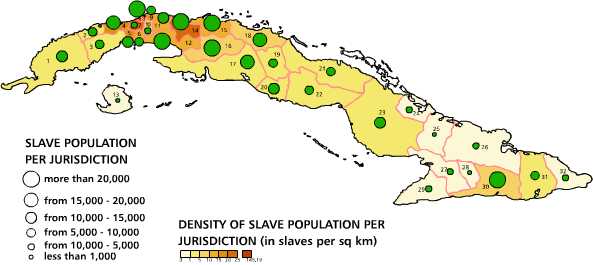

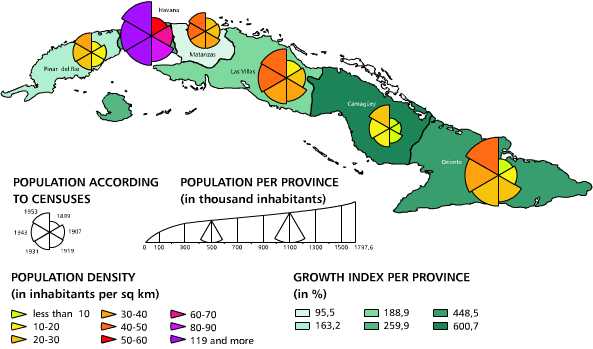

One of the distinctive traits of colonial settlements was the unequal distribution of the population throughout the island. This was the case since the first years of Spanish colonization and remained consistently so until the 20th century, with the nuances caused by each stage of economic development. Census data, mainly that taken from the 1862 census, a crucial transitional moment in Cuban history, clearly show this reality and are the basis for the understanding of these problems in the 20th century. The areas with a larger population were always those with a stronger economic development, since they became the center of the main migratory movements.

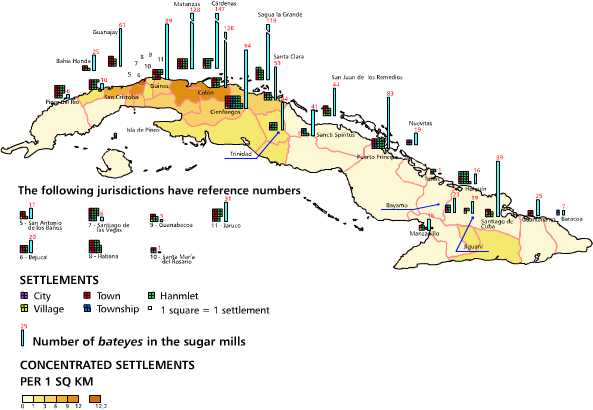

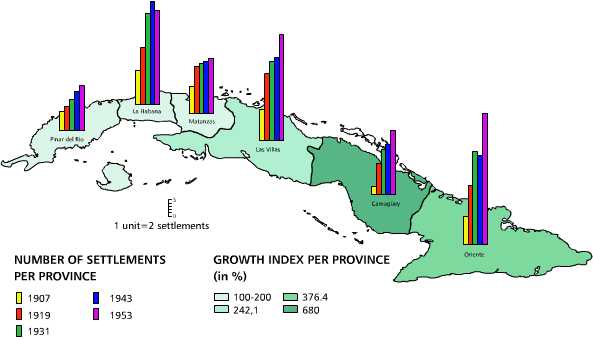

As a result of the population growth and of the extension of areas opening to inner settlement processes, the number of settlements increased continuously, since each economic object gave rise to settlements whose characteristics depended on the requirements of their respective forms of organization, production and land tenure.

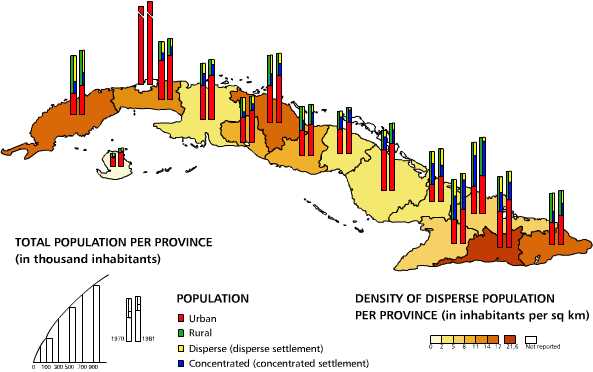

The analysis of this phenomenon has frequently been approached from a classification that groups population on the basis of two indicators: urban and rural. The first one includes all the persons reported as living in settlements and, the second, all those living in farms; however, identifying as urban all the localities in the census does not reflect reality and may be misleading. Together with big towns and villages, the censuses include small groupings often formed by no more than four or five houses standing next to each other. That is why the maps in our Atlas are based on the two main forms into which the population has historically settled: dispersion and concentration of inhabitants. This allows us to highlight other typical traits of Cuban population.

The population living in agricultural dwellings -- estates, cattle ranches, tobacco and coffee plantations, farms, work sites -- were classified as disperse population. A small number of persons usually lived in them, at times isolated and scattered in the fields. Concentrated populations were those reported to be living in cities, villages, towns, hamlets, townships and sugar mills. This latter category appeared in documents of those times as farms, while in truth their dwellers lived in the batey (the sugar-mill town) that, no matter how small, had a larger number of inhabitants than many of the settlements appearing in the censuses. The analysis of these data shows a higher population in concentrated settlements: 53 per cent of the total in 1862, mostly because of the large number of inhabitants living in settlements, particularly in jurisdictional centers. This was a process that began during the first years of colonization, because of settlement patterns implemented by the Spanish colonizers. The sugar industry must also be taken into account: 16.6 per cent of the population lived in sugar mills; in some of the main jurisdictions engaged in its activities, figures were much higher than this average. Meanwhile, large areas were unpopulated or practically uninhabited. Thus, the highest number of concentrated settlements could be found in the Western part of the island.

disperse population was higher in the areas where tobacco and root vegetables were grown. The jurisdictions of Pinar del Rio and San Cristobal, to the West, may serve as examples. In them, 84 and 57 percent, respectively, of the population lived in tobacco plantations. Animal husbandry was another important impact on dispersion. Puerto Principe (now Camaguey) is a case in point, even when it is among the jurisdictions with a higher number of inhabitants, due to the high concentration of the population in its main town. Cattle breeding, occupying more than 70 per cent of its vast territory, required only a small number of inhabitants, scattered and irregularly distributed within it. Although it is true that concentration prevailed in the Cuban population patterns during the 19th century, the number of persons living in a disperse manner, above all among the rural population that was the seed of our present peasantry, was already high.

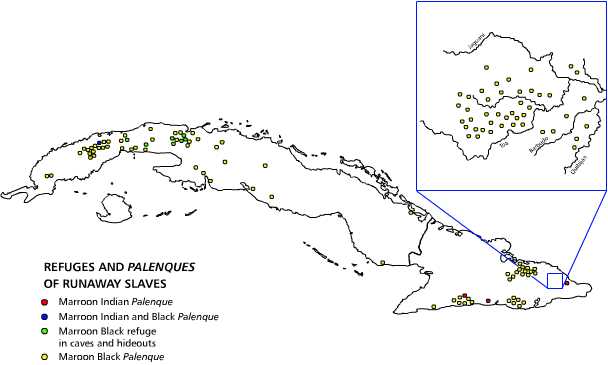

In the colonial period, settlements established by run-away slaves must also be taken into account. They reached a larger number in the peak moments of slavery and the resulting increase in exploitation. In spite of the continuous persecutions they suffered, many of them were able to create relatively stable systems of social and economic relations, which they maintained for a long time. Some of our present settlements emerged out of them. Their geographic distribution did not coincide with the areas with larger slave concentrations. At times, maroons had to travel long distances and settle in dense woods where access was difficult. There they built their dwellings and planted their crops within a limited space.

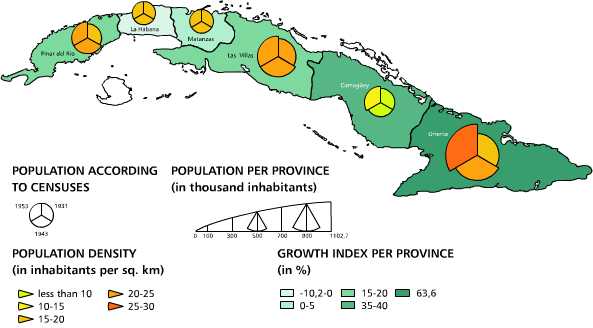

An accelerated process of population growth characterized the republican period. A new trend of population and territorial expansion towards the East of the island began in those years. This trend, which could be forecasted in the previous century, was mainly caused by the development of the sugar industry. As the 1943 census stated: "The history of the republican period as regards to population is the history of the development of Camaguey and Oriente provinces."

From the available data, comparisons between the number of settlements in the 20th century and those in the colonial period cannot be made. Census statistics only include settlements with more than a thousand inhabitants. But qualitative information obtained from field research shows that rural settlements followed a growing trend.

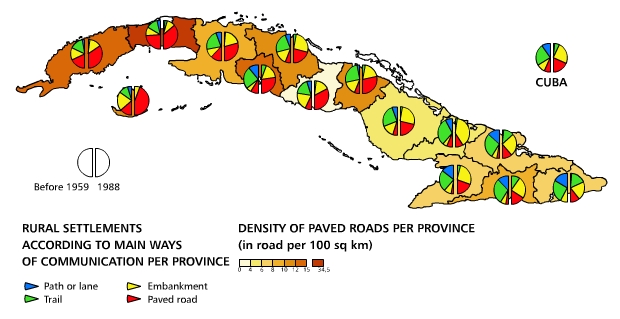

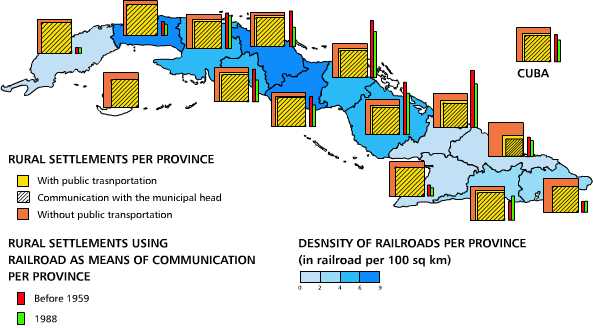

Population growth, together with the increase in agricultural activity, contributed to the emergence of a large number of rural settlements. Also, the new means of communication, such as the railroad and the central highway, had a considerable impact in this process since many settlements appeared next to them. Rural settlements had their start in very many diverse motivations.

Functionally, many of them were nothing but a reservoir of agricultural manpower; some meant the solution to the great housing and work problems of the rural population, that at times lived next to rural roads with no link to the economic work places in the area. Also, settlements that were to become social and economic centers emerged with a population that was largely heterogeneous from the occupational point of view. Several types of small commercial and service businesses satisfying some of the needs of the neighboring population were commonly established.

Historically, the Cuban peasant population has lived in the center of the land they till. Thus, there have been many disperse settlements whose specific characteristics have always depended on the forms of organization of the economic activity they were engaged in. Peasant communities or townships, typical of other countries, are not characteristic in Cuba. However, in some areas with very specific objective conditions, small concentrated nuclei did exist, above all when farms and lots were distributed one next to the other in a given piece of land. These settlements could be considered as an intermediate step between rural dispersion and concentration.

Census information does not offer data to accurately define the number of persons living in a disperse way in this period, but if the agrarian structure reflected in the censuses is analyzed, it can be seen that together with the large estates that controlled most of the land in the country, there was a high number of small lots, that exercised a direct influence on the character of the settlements, given the historic trend of the Cuban peasantry of living in their own piece of land. Of course, dispersion has never been specific of peasant population. Many agricultural workers lived this way, especially in the period before 1959.

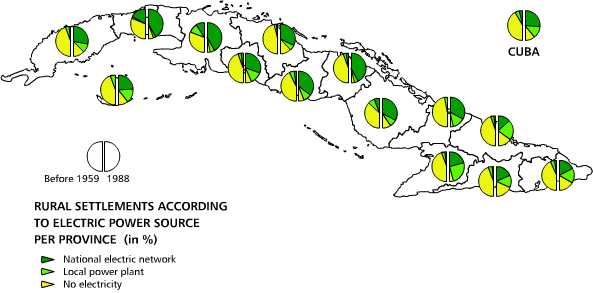

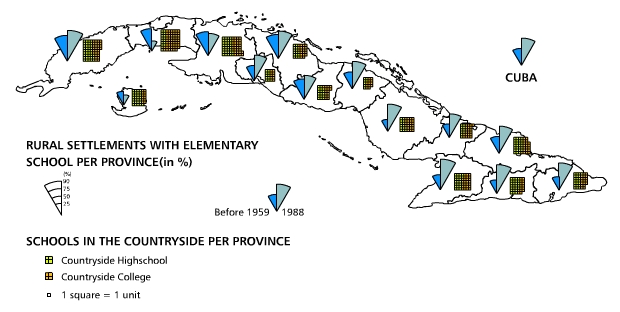

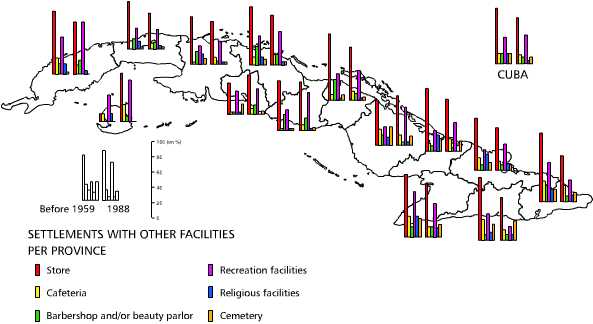

From that date on, a process of transformation took place in rural areas that had a profound impact on the restructuring of traditional rural settlements. Among the revolutionary changes were the establishment of state stores, schools, health centers, social clubs and other social institutions and facilities, and also the extension of electric power lines, all of which have contributed to improve the living and working conditions of the rural population. The intense building of rural roads and paved highways that put an end to their traditional isolation is another important factor in these changes.

Many of the main rural localities reached their present size and importance as a consequence of the above mentioned changes. The fact that migrant agricultural workers or those living in very unstable settlements went to live in them was an important factor in the growth of their population and of their economic and social activities. Also, many peasants have moved to rural towns or to urban areas.

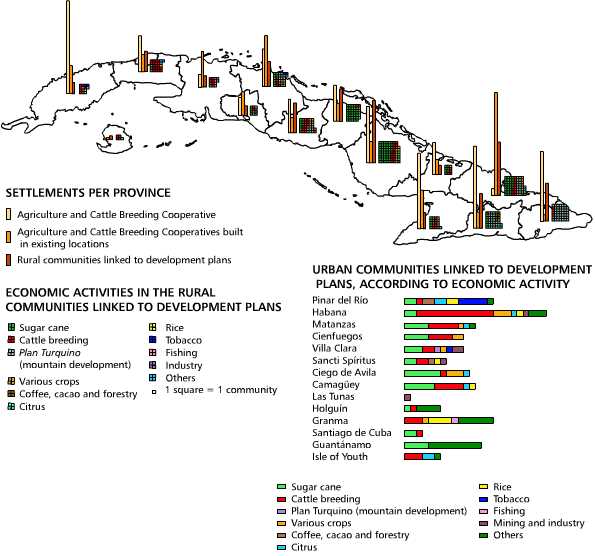

In the reorganization of agricultural and cattle breeding production and of the system of settlements, an important role has been played by the communities created as part of development plans started in the ′60s. The use of modern agricultural technology in agreement with the requirements of national economy made it necessary to unify great extensions of land in specialized agricultural plans, with the resulting concentration of rural population, that was mostly isolated and scattered, into townships with new types of houses, with electric power and running water, schools and other social facilities. Given their conditions, many of them reached the category of urban towns.

In the peasant sector, the Agricultural and Cattle Breeding Cooperatives (CPA), in which peasants united their individual lots and lived in new townships, had the deepest impact in traditional rural settlements. At times, houses were built next to nearby towns and the already existing structures could be used without large additional investment.

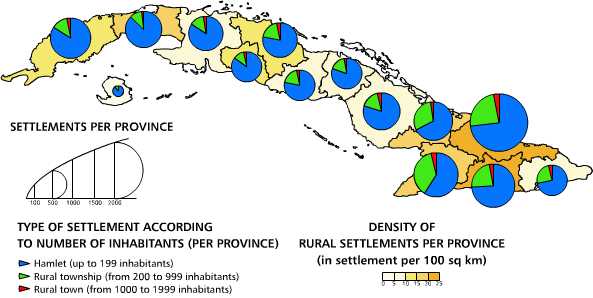

All these transformations have deeply modified the traditional settlement system. Today, the rural population can be found grouped in traditional hamlets and rural townships or in the new settlements built after the triumph of the Revolution. There are still many disperse settlements, but they show a declining trend. This is also the case with concentrated settlements, mainly the ones with a small population. Even when there are still more hamlets than rural townships, they diminished greatly in the 1970-80 inter-census period.

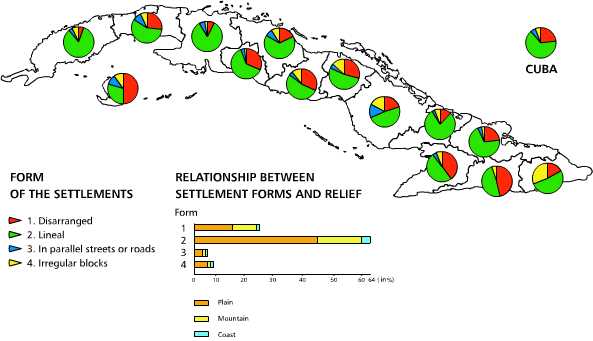

Since most rural settlements follow communication routes, lineal plotting in its multiple variants has always prevailed. However, lineal townships almost never take straight lines. In general, there are irregularities caused by relief and by the path of the roads and, in the case of hamlets, also by the irregular distribution of lots. All of them create disordered forms. In settlements inhabited by agricultural workers and, specially, in those classified as rural townships, a larger density in the grouping of houses and other buildings can be seen. Townships with blocks and parallel streets or roads are less common, but have increased in recent years, given the planned building of the settlements.

In the new settlements, the disappearance of many auxiliary facilities once used for agricultural production, animal husbandry, protection against hurricanes, and other purposes, has given rise to many variations in the traditional social and economic complex of peasant dwellings. With the new organizational structures, collective facilities were established for these purposes. The large backyards of the traditional peasant dwellings disappeared in the new settlements. However, due to the existence of age-old habits and customs, some auxiliary facilities have begun to reemerge in a strong contrast to the new type of houses.

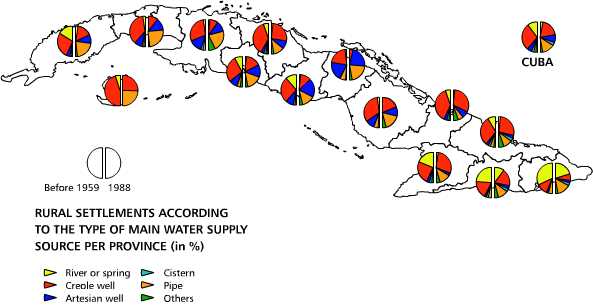

In the moment when our field work was in progress, a decline in the use of rivers as a source for water and an increase in the use of pipes were outstanding. However, creole or artesian wells are still the most extended source of water supply in rural areas throughout the country, with a great variety of forms and systems for water extraction.

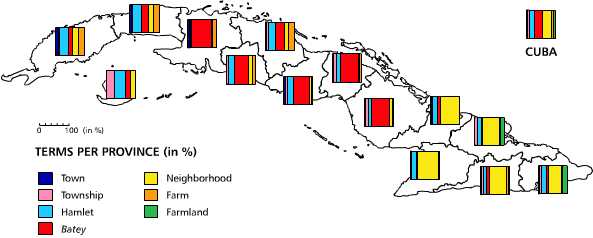

The categories used by the population to identify the place in which they live has also been one of the topics researched. They vary greatly throughout the country. In general, terms coined in various historical periods are used, not always identifying population nuclei, but political and administrative divisions, such as cuarton and barrio. Among regional specific characteristics, the extended use of the word batey in sugar cane areas, to identify the settlements linked to this type of economy, may be highlighted.

Rural settlements are a social phenomenon undergoing a series of variations having to do with many different factors, but their close dependence on the social and economic elements under which the cultural patterns giving them stability and continuance emerged were clearly confirmed by this research. In cases where settlement patterns characteristic of other groups and cultures were transplanted, their existence has been short-lived.

Dr. Juan Antonio Alvarado Ramos

Maps

-

Population distribution. 1862

-

Concentrated settlements. Middle of the 19th century

-

Distribution of slave population. 1862

-

Runaway slave settlements in the 18th and 19th centuries

-

Urban and rural population. 1899-1953

-

Rural population. 1931-1953

-

Settlements with more than 1,000 inhabitants. 1907-1953

-

Population dynamics. 1970-1981

-

Concentrated rural settlements. 1981

-

Rural settlements built after. 1959

-

Form of rural settlements

-

Ways of communication

-

Public transportation

-

Water supply sources

-

Electric power

-

Educational facilities

-

Rural health service facilities

-

Other facilities

-

Popular names of rural settlements

Videos

- Ethnic history «

- Rural settlements

- » Rural houses and auxiliary facilities