The furniture and furnishings are fundamental elements to achieve a meaningful characterization of the material culture of a human group; however, in Cuba studies on this topic have been very few and partial.

Apart from some works on the history of urban furniture, limited to the description of the furniture in some colonial family houses and samples of clerical furnishings, before the research made for the Cuban Ethnographic Atlas, there were no texts on rural household furniture.

The only existing written information were brief and modest notes on some types of furniture and tools that were very well-known because of their ancient and extended use in Cuba. This was the case of hammocks, cots, taburetes (a type of chair), tinajeros (stands for earthenware jars), catauros, graters, jibes and jicaras. These notes, scattered in the literature of West Indian chroniclers, in travel books, period chronicles, campaign diaries, narrations and articles of manners, customs listings and censuses, most often merely stated their existence, but made no substantial evaluation that could be used as a basis for characterizations.

However, an observer visiting at least once in his or her life any rural area in Cuba would see an interesting array of pieces with very specific traits, the bearers of a secular tradition that for minor devices dated back to the Cuban Indian cultures, that is, before the Spanish left their mark.

Thus, the simple referential knowledge of these evidences, the absence of studies on them and the unstoppable passage of time -- that always entails losses, changes and the emergence of new values -- were reasons enough to start, develop and conclude research, analyses and classifications bearing witness to this long and multiple human endeavor contained in the furniture and ware of Cuban rural households.

If one adds to this the rapid economic and supra-structural transformations that began in the ′60s throughout the national territory and, therefore, in its most isolated rural spots are added to this, these evident reasons would become urgent calls to the immediate need to grasp and perpetuate the most ancient values those pieces embody and give them the attention they deserve in the general context of Cuban culture. This has been the main intention of this study.

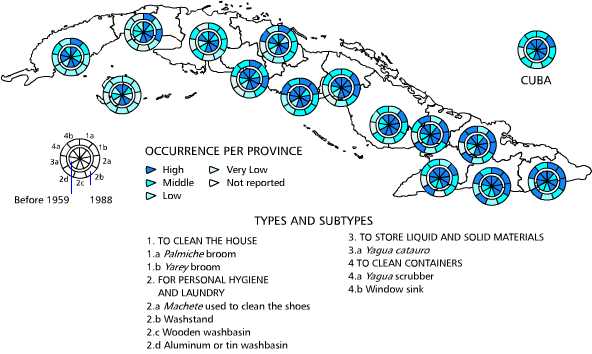

Because of the multiplicity of functions and forms of rural household furniture, as data and samples of the different types and variants were gathered during the research, the need emerged to establish denominations and classifications, since it was a very complex study encompassing the furniture in every room in the household. Thus, pieces of furniture and ware in the house were grouped according to their functions and formal similitude.

The various groups of pieces of furniture and wares in Cuban rural houses are simple and very useful. Before 1959 it was almost impossible to find a piece of furniture or houseware without a given function, a practical and specific use.

They were made with materials found in the surroundings, most of the times by members of the family or by carpenters living in the area who had empirically learned their trade. Ornaments were few, because the requirement to give everything an immediate use prevailed, but durability was guaranteed by the use of hard woods and the wise work of people who knew they did not have time to lose, nor money to replace things in a short time.

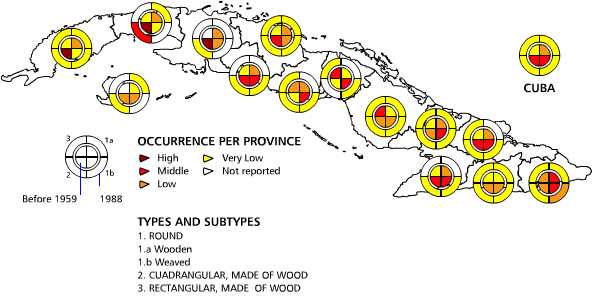

Men and women in the countryside believed household furniture was made to "last a lifetime", so it is not surprising that many of the pieces appearing in the following maps belonged to several generations of a family. This is the case of many taburetes -- to which only the hide back and seat had to be changed --, many benches, tinajeros, dish holders, beds, lamp holders and shelves for various uses.

Before 1959, rural household furniture was made up of pieces to sit and to sleep on, tables to prepare and serve the meals, shelves to keep food and containers, tinajeros for drinkable water, lamp holders, wardrobes and the required stove, with the form of a big box, in the room where food was cooked. The excusa baraja hung from a beam on the roof over the stove. Its main function was to keep salt, cheese and some processed food out of the reach of insects and rodents.

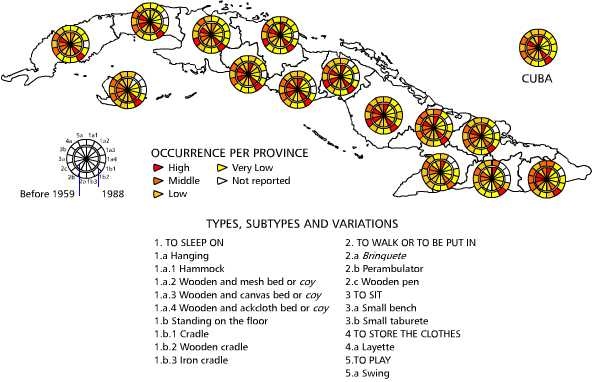

As to children furniture, even when they used the rest of the pieces in rural households, no matter how scarce the economic resources of a family, there was always a small hammock or bed, and a small taburete or bench for the children. Although there are testimonies from many parts of the country on the existence of brinquetes and coys, this children′s furniture was most frequently found towards the center of the island and in Camaguey.

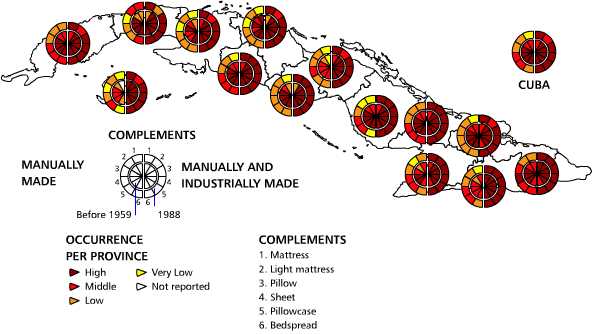

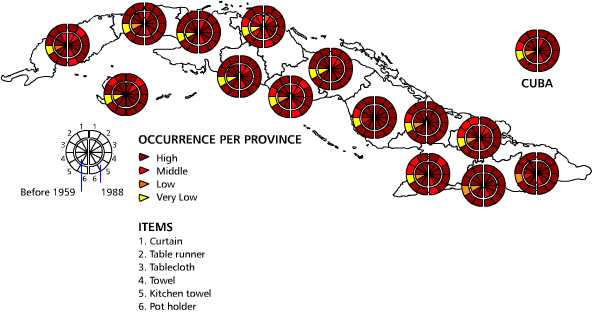

Needlework deserves special attention. Before 1959 and some years later, beautiful household pieces, the compliment of bedroom furniture, have had a meaningful place in the context of rural houses. There are many ways to make, decorate and adorn sheets, pillowcases, bedspreads, curtains, hand towels with cloth, thread, fibers, seeds and many other materials with which almost all the elements of the Cuban flora in the area were to be portrayed.

Specific monographic studies would be required on the many implements used in the kitchen-dining room of Cuban rural houses, in personal and house hygiene, to store liquids and solids, but, of course, this is not the purpose of our preliminary approach.

However, the harmonic coexistence of old traditional implements with elements introduced in these last decades should be highlighted.

At times, next to an electric blender, a guiro mug for "cloth strained" coffee, "because it gives a better taste", can be seen in a wise and natural balance. A jibe weaved with yarey may hang from a nail waiting to sift cornmeal or cassava flower. Washbasins, brooms made of palmiche (palm fruit) and a catauro full of water are to be found in the yards. Jibes, jicaras and catauros, just as those our natives used, can be found next to rice cookers and color TV sets in the living rooms.

This happy communion began in the ′70s, as a natural consequence of the transformations that the revolution brought to the countryside, which had an impact on every area of daily life and, therefore, in households and their furniture and houseware. The Cooperatives for Agricultural Production were significant in this context, since they built communities and houses with new characteristics.

As can be imagined, changes in the pieces of furniture were also gradual and, as happened with other things, old and new elements coexisted for a long time in houses, areas or regions. When this research was carried out, living room suites, almost always of precious woods, with ornamental straw or wickerwork, were to be found, together with the old and comfortable taburetes that are now kept in other rooms, mostly the kitchen, but are still preferred by men for their customary afternoon rest, after they finish with their agricultural, agroindustrial or cattle-breeding chores.

Also, the new dining room suits, with wood and glass sideboards, had not totally displaced pottery shelves (loceros) nor the long wood tables planed a thousand times, nor benches and stools where in an unchangeable century-old ceremony peasant families sat to have their meals.

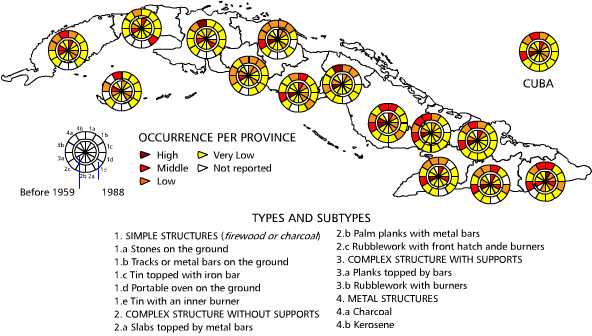

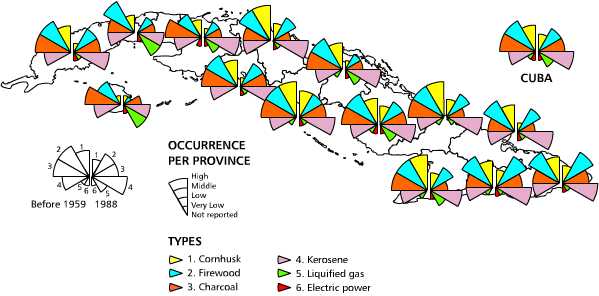

The fate of the enormous firewood and coal stoves and their excusa barajas was different once the rural families went to live in the new brick or pre-fab houses. A large tile table with a metal sink, that replaced the tollas or window sinks, contained a new artifact: a kerosene range. The inclusion of this useful metal device in most of the Cuban rural areas, together with refrigerators or iceboxes, gradually replaced the tinajas and, thus, the traditional tinajero. The same thing happened with the traditional lamps and lamp holders.

Changes in rural households have been so many that it is impossible to mention them all, but some general elements can be found. According to its most universal traits, traditional rural furniture has been characterized by its formal simplicity, its artisan construction, the use of materials from the environment, the fact that it is useful and necessary and has fundamental forms and characteristics with traits similar to those in the Spanish American and Euroindian worlds, because of the ethnic influences forming part of Cuban culture since very early times.

It should be pointed out that although the names of some of the pieces of ware may change with the region, as is the case with the vaseros (glass shelves), that in some areas are called jarreros (mug shelves), loceros (China shelves) or plateros (dish shelves), their formal characteristics and uses are similar to those in rural households in other countries. The same can be said of all their families and typologies. That is why for the furniture pieces we used the names that were most extended throughout the national territory or that were consistent with the most general forms of Cuban popular speech.

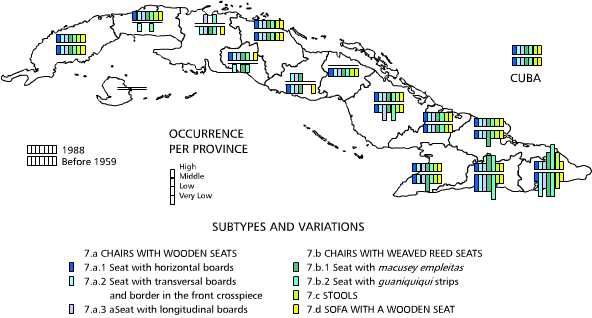

The so-called guaniquiqui seats are a valuable testimony of the contribution of other Caribbean peoples to our material culture. According to many researchers, they were introduced and accepted only in the areas with a strong presence of English and French-speaking West Indian laborers who arrived in our country to work in the sugar industry. According to numerous oral and written sources, guaniquiqui or guaniqui weeds -- generally in combination with macusey -- had only been used in Cuba before in basket weaving. As can be seen in the map on this type of furniture piece, they can be more easily found in provinces with a strong West Indian presence. In the rest of the country, this type of furniture is only found in households of people of Haitian, Jamaican or Barbadian descent or of persons taught by them.

The use of guaniquiqui furniture has recently increased, among other reasons, because of its beauty, and it is frequently seen in hotel lobbies and in some living rooms in urban houses.

Ornamental manufacturing of tinajeros, that were to be found in houses of peasants from the Canary Islands or Old Castile, should also be highlighted. Because of these specificities, they may be closely linked to that ethnic and cultural background.

The following conclusions may be drawn from this first approach:

Whatever the economic situation in the household, there has been a strong artisan tradition in every rural area in Cuba, intimately linked to the furniture and ware in rural households.

The existence of this type of furniture and furnishings in Cuban rural homes reflects an organic and consistent way of life, revealing the existence of solid, well-defined and lasting cultural roots no matter the gradual or sudden transformations that may take place in any aspect of material culture.

The evidence is there: there still is a traditional cultural way of life.

Nancy Perez Rodriguez

Maps

-

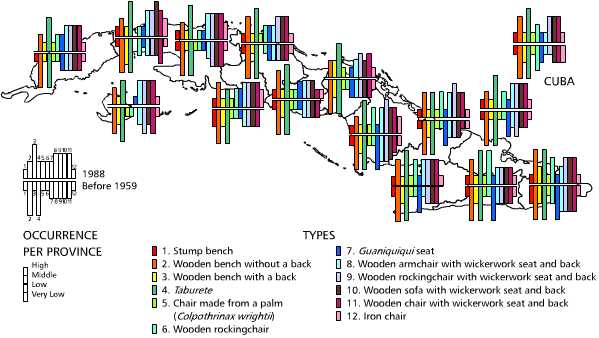

Furniture to sit on

-

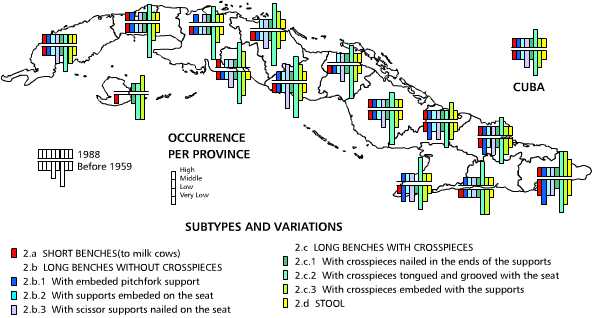

Wooden benches without backs

-

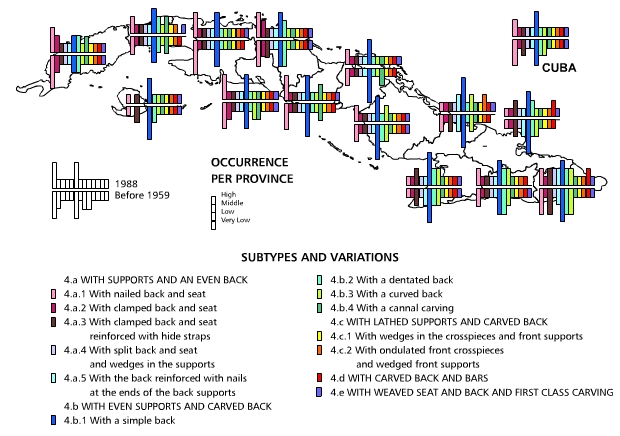

Taburetes

-

Guaniquiqui seats

-

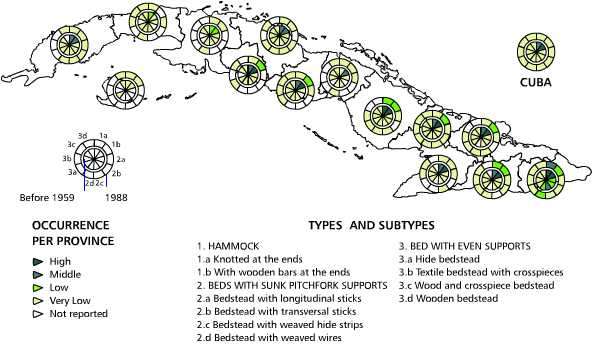

Rustic furniture to sleep on

-

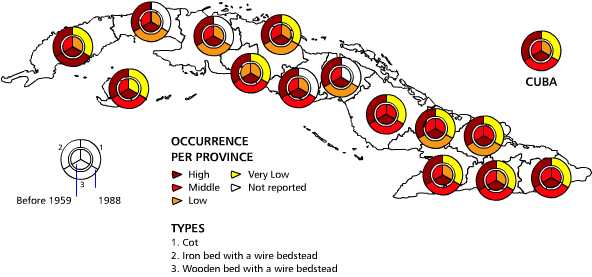

Conventional furniture to sleep on

-

Complements of the furniture to sleep on

-

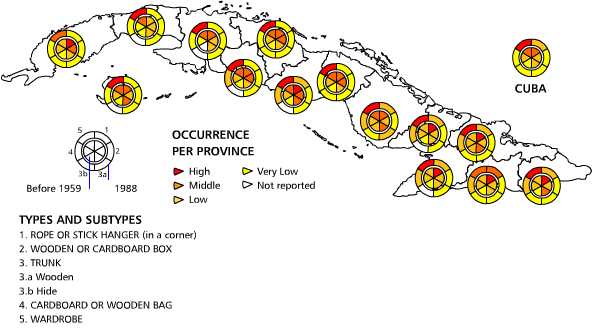

Furnishings to store clothes and other personal items

-

Childrens furniture

-

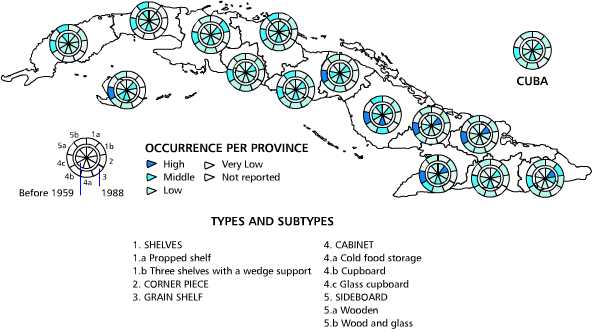

Furniture to keep containers and/or food

-

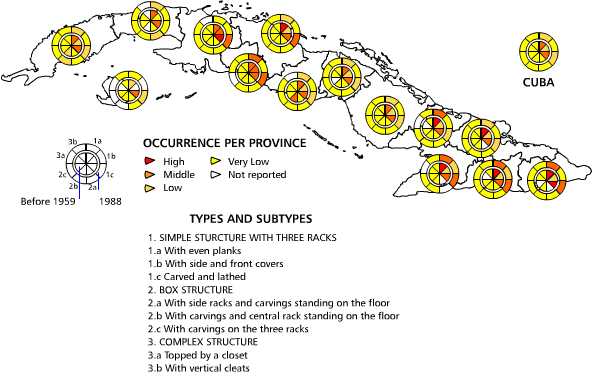

Excusabaraja

-

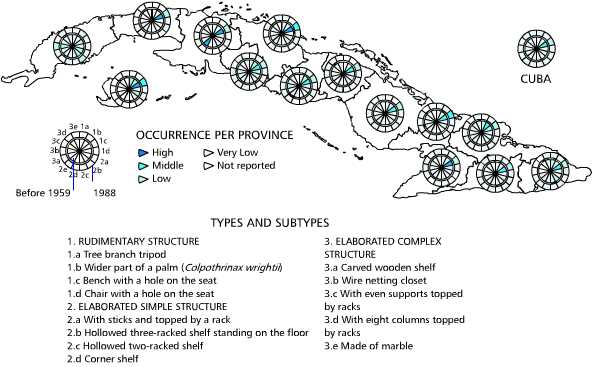

Tinajeros

-

Dish holders

-

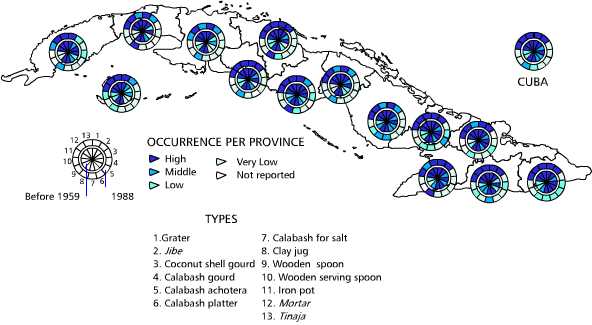

Some utensils in the kitchen-dining room

-

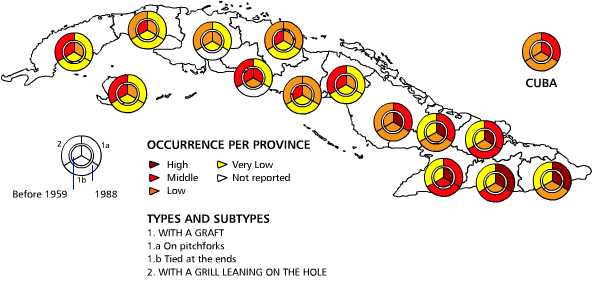

Hole on earth stoves

-

Stoves

-

Fuels

-

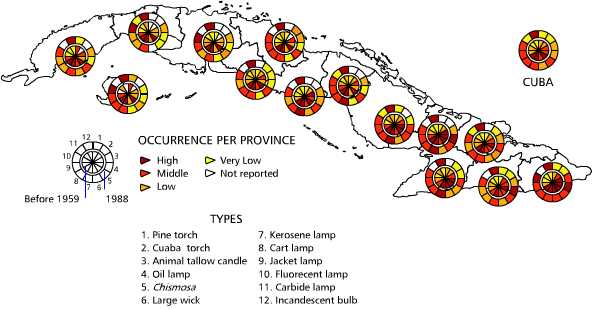

Lighting utensils

-

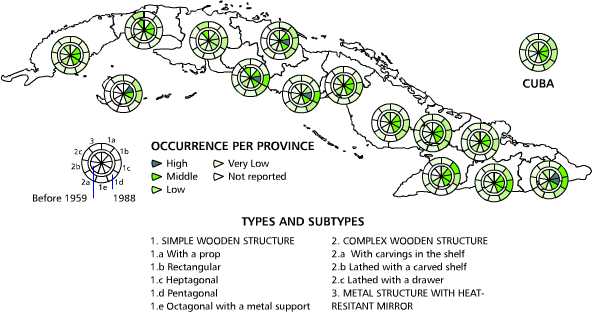

Lampholders

-

Various house items

-

Other items in rural houses

Videos

- Rural houses and auxiliary facilities «

- Furniture and furnishings in rural households

- » Food and breverages