Internationally, the study of farm implements has a long tradition and a large bibliography approached through various specific disciplines. Specialists in agrarian history research farm implements in the context of the general development of agriculture. With the analysis of interrelationships between economic history in a given region or country, and the development of agriculture, the place of implements in the dynamics of change comes to the fore. Practical agronomists have gathered information about the advantages of traditional implements, which may still be attractive, feasible and even necessary in developing countries.

Equipment used for tillage and other agricultural activities is very important in ethnographic studies because they held find specific relationships or characteristics between a given type of implement and an ethnic group. These characteristics are present in the massive and stable components of daily lived culture with distinctive traits.

Towards the end of the 19th century, research on early agriculture found that the development of plowing implements depended on social, economic, historical and cultural factors. based on this research, a distinction was drawn between functional and formal traits of agricultural technology. Functional traits are defined by physical and geographical conditions. Formal traits are developed independently, or relatively independently, from these circumstances. Formal traits appear mostly in the specificities of the construction of the body of the implements and are a reflection of historical and cultural traditions, among them, ethnic traditions. Historical and cultural traditions for the manufacturing of agricultural implements are structured in the locations where they were created, under the influence of ecological, technological, social and economic factors. At the beginning they are purely technical, but with time they acquire stability linked to the practice of many generations and, thus, traditions emerge.

In Cuba, the early presence of tilling implements is reported among natives who practiced a type of manual agriculture with the use of the coa, since they were not acquainted with draft animals, such as oxen, horses and mules. Under Spanish colonization, this type of agriculture declined gradually, although it never disappeared, as hoes and plows replaced them. Plows brought with them an array of auxiliary tools, that formed its complete cropping system. These in turn implied the introduction of new techniques, training, habits and knowledge on Agrometeorology based on traditional popular agriculture from Spain and the Canary Islands.

To understand the development of Cuban agriculture at the beginning of the colonial period as reflected in the tilling implements that were used, one must review land tenure and the way land was used. Settlers received a given piece of land depending on their social standing. During the 16th century, agriculture was a minor but significant occupation. The natural conditions Spanish immigrants found in the island, where none of the three Mediterranean staple crops -- grains, grapes and olives -- could be grown, implied the need to readapt themselves to new types of production.

The 17th century saw the emergence of cattle breeding, especially bovines. Bovine production did not require a large labor force -- an overseer and two or three slaves were enough for a rather large piece of land. In the second half of the century, a reorientation of cattle breeding took place, that at the beginning satisfied the demand for meat, hides, milk and dairy products. Also, the development of agriculture, particularly sugar cane, demanded the breeding of oxen.

In the 18th century, agriculture changed from subsistence to mercantile production. Products manufactured from sugar cane and tobacco went first to domestic and then to foreign markets at an early date. Of course, local agriculture satisfied part of the demand of produce. A new crop, coffee, entered the country in that century. Coffee was mainly planted in the Eastern part of the island, but also in the Pinar del Rio ranges and to the south of Havana, in the Western region, by coffee planters who came from Haiti, fleeing from the civil war of liberation.

The tilling, sowing, ridging, cleaning and felling the sugar cane fields were done with manual implements, and, in contrast to the case of tobacco, slaves were the main manpower. Towards the middle of the 19th century, in some parts of the country, particularly in Matanzas, there was a definite transition to the industrial manufacturing of sugar, but this did not extend quickly to the manual work in the fields nor to the cropping.

At a time when other countries underwent an intense search for the improvement of tilling implements, in the main branch of Cuban agriculture, on which all the economy and social relations were based, the exploitation of slaves increased. In sugar cane plantations, the soil was tilled with iron pointed janes and hoes. Hoes were widely used, even in places where Creole plows furrowed the earth, since seeds were covered using hoes.

When slave manpower began to diminish in the country towards the midst of the 19th century and prices of slaves increased, sugar cane plantation owners tried to find a way out of the situation through the mechanization of agricultural work.

From that moment on, there was an increasing demand for the importation of plows improved with moldboards, cultivators, and ridges.

The availability of this type of equipment in plantations and estates depended largely on the economic position of their owners or usufructuaries. Small farmers had to make do with Creole plows and hoes instead of cultivators.

Towards the last third of the 19th century, the political situation in the country, especially the two devastating wars of independence -- from 1868-78, in the Eastern part of the country, and from 1895-98, in all the territory -- made the development of agriculture very unstable. Small sugar factories closed and the gradual abolition of slavery started. These factors contributed to the emergence of a new system of land exploitation, that was to be known as colonato (tenantry). Some sugar cane plantations were divided into farms and lots of various sizes depending on the financial position of their owners.

In the 20th century, during the neocolonial republic, the use of manual implements in the clearing of woods and virgin lands was maintained, as well as for crops grown in mountains and plains. However, plows with all their auxiliary equipment prevailed in agriculture.

At the triumph of the Revolution in 1959, structural changes took place in agriculture. Latifundia were eliminated and state farms were established in most of the expropriated land. Other lands were distributed to small farmers, mainly former tenants, sharecroppers and squatters. In the state sector, traditional implements were barely used; the breaking of new ground and planting were carried out with mechanically driven equipment. Hoes were used only exceptionally when machines could cause harm to the crops. In small private lots and cooperatives, new equipment and tractors were also used, even when traditional implements, such as hoes, Creole plows and improved plows, driven by animals, also found a place.

Basic principles allowing a methodological consistency were used to classify agricultural tools and implements. A set of indicators divided into two chronological levels was chosen as a starting point: those having to do with the function and use of each implement and those having to do with their morphologic and constructive elements. Another principle was that of classifying implements according to their source of power: those powered by human or manual force and those driven by animals.

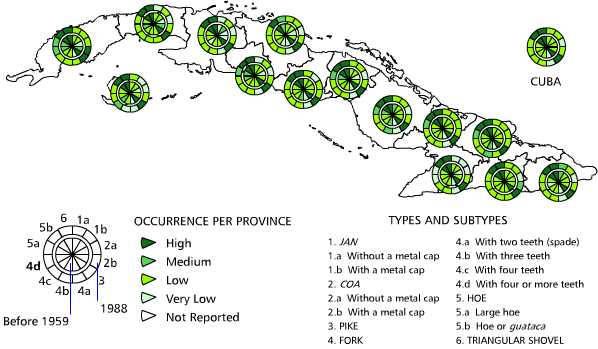

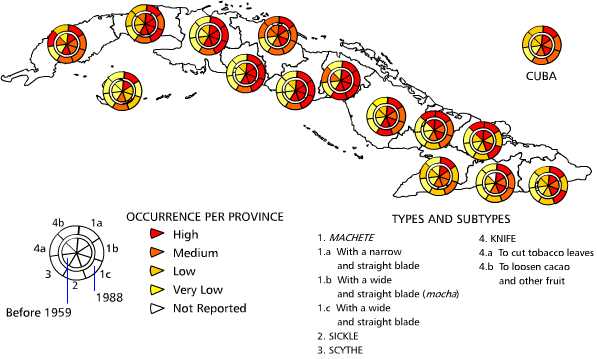

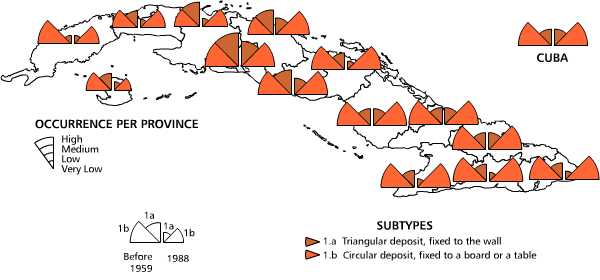

The typological tables included in the maps show the types, subtypes and variants of the implements. Digging and sowing implements include coas and janes, characteristic of native agriculture and still in use, together with hoes, grub hoes, forks, picks, and triangular shovels, whose use dates back to the Spanish colonizers. Among the manual harvesting implements there is a diversity of machetes to clear the ground, particularly for sugar cane, and sickles, very useful in rice harvesting. Scythes, very extended in Spain for grain harvesting, were only used in clearing grass and were not frequently seen in the Cuban countryside. Blades to cut tobacco leaves are widely seen in tobacco regions and they use is limited to this specific purpose. The same thing holds true for cacao blades, although these are also used to cut thorny plants for farm fencing. In this case they receive the name of rozaderas.

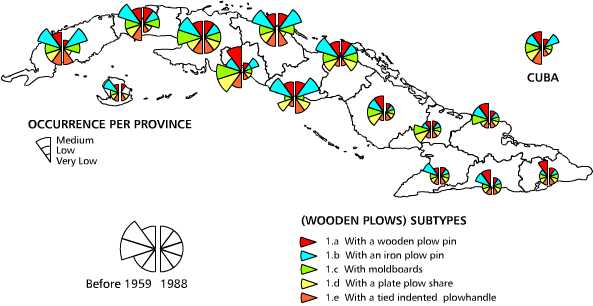

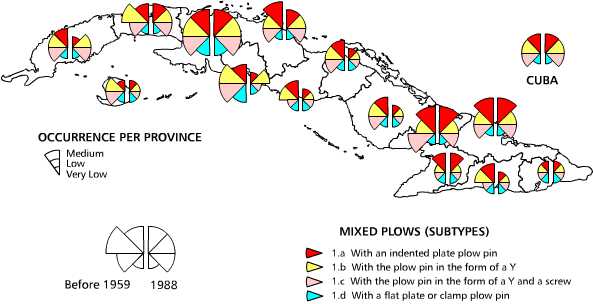

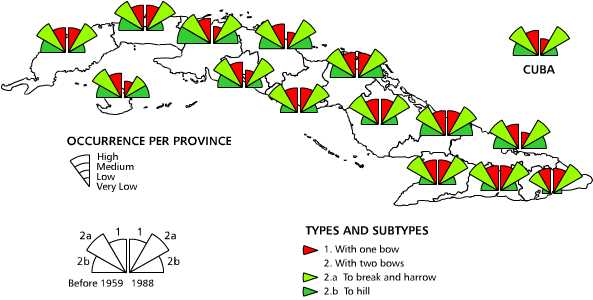

Creole or wooden plows, typical in traditional agriculture, are used for breaking the ground, crossing, recrossing, hilling, removing the banked-up earth and covering the seeds. Since they do not have moldboards, they do not cover the seeds with plowed earth. They exist in several variants according to the constructive characteristics of their work and steering elements. Mixed plows, or espolones, have a long beam and only one handle like that of the Creole plows. Their plowshare and moldboard are similar to those in the improved metal plows. Their constructive characteristics are the result of combining traditional elements of the Creole plows with others from modern equipment.

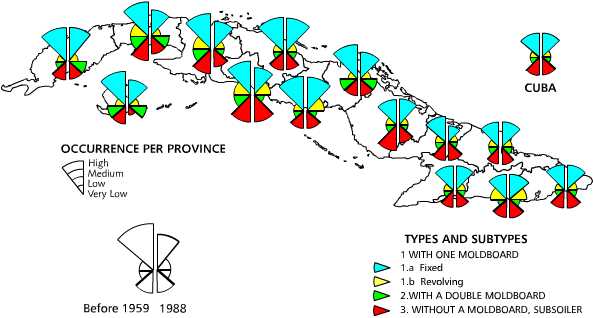

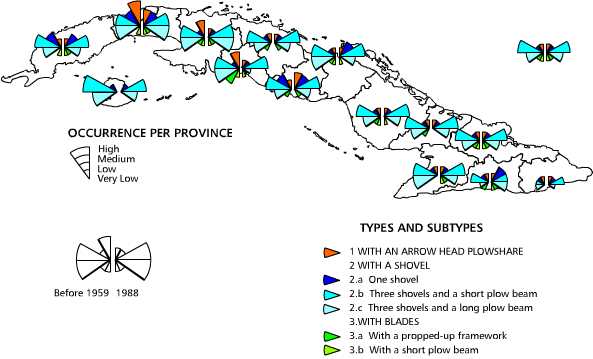

Improved metal plows, with a short beam and two handles, have one or two fixed or revolving moldboards. Lanceolate plowshares to break and remove subsoil layers are among them. Cultivators include arrowhead plowshares, triangular or heart shovels and plowshare-blades, the latter ones to weed and clean the land.

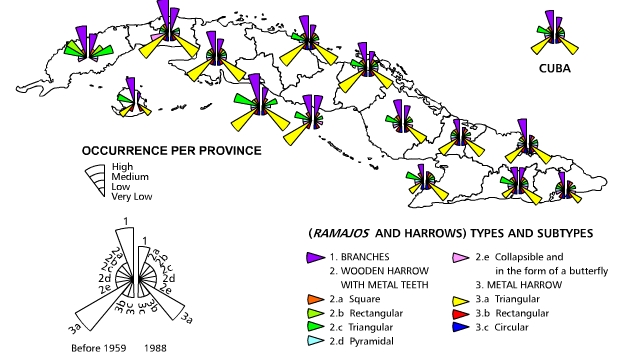

Among the plows, there are also the ramajos, the harrows and the wooden or plain harrows (without teeth). They are used to undo clods of earth, clean thistles from plowed land, smooth it and cover the seeds.

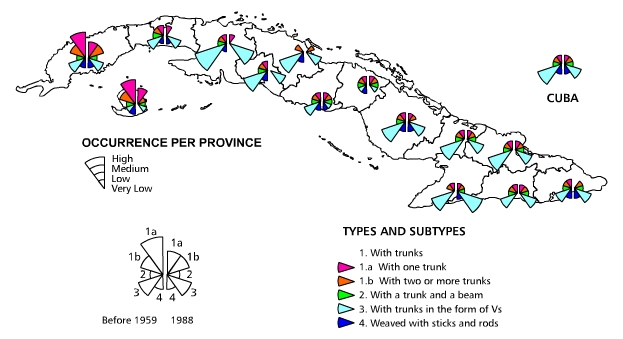

Yokes appear in animal driven implements. Oxen are yoked to various types of plows and harrows. They may be simple or double, according to the number of oxen used. Simple yokes are used in shallow tilling, weeding and grubbing. Double yokes are used in deep tilling, breaking the ground, furrowing, hilling and removing the banked-up earth. Cuban yokes are similar to Spanish strap yokes, but less ornamented.

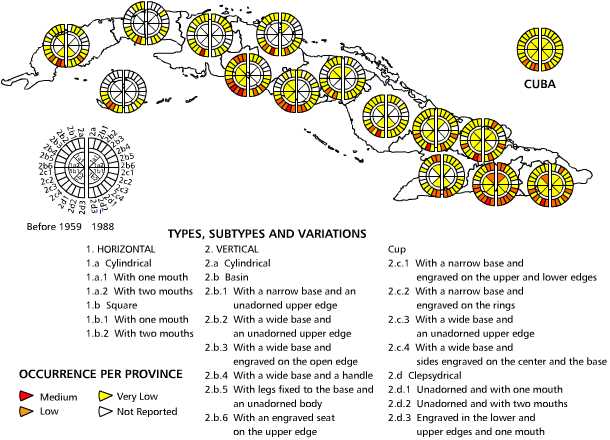

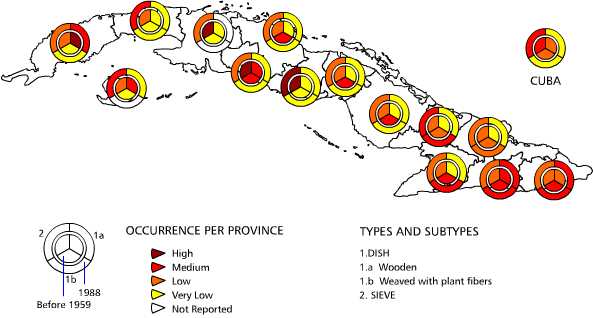

Another group of implements is specifically designed to process the produce, specially that consumed in the farm household. Among them are mortars or pilones to pound root vegetables, dehusk grain or grind roasted coffee beans. According to the way they stand on the floor, they are horizontal or vertical, and take many different forms. They have one or more mouths or cavities for the products to be processed. Winnowing forks finish the task mortars begin by removing husks and other undesirable elements obtained when pounding.

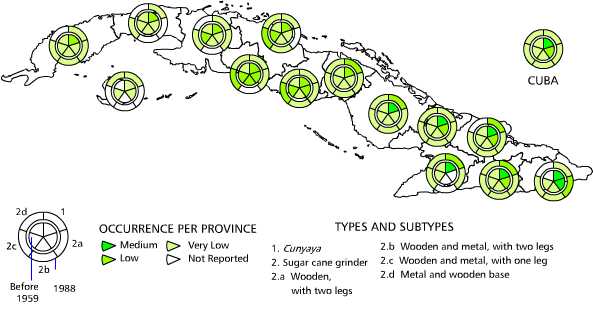

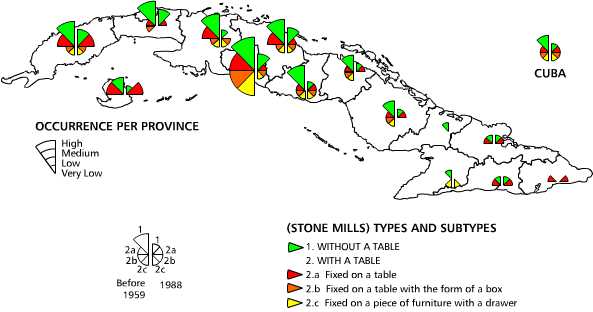

Stone mills are outstanding in this group of tools. They are typically found in rural households. Spanish settlers, specially those from the Canary Islands, brought them in the early colonial period. They are used to mill wheat and corn in the household. Iron mills have the same function of stone mills. They were imported from the United States in the second half of the 19th century. Even when they were industrially manufactured, their ancient and customary use allows them to be considered as traditional.

The section ends with maps showing various elements from the traditional agricultural system. This system is defined as a set of agricultural and technical actions empirically followed by farmers using natural or artificial elements to increase the fertility of the soil and obtain better crops.

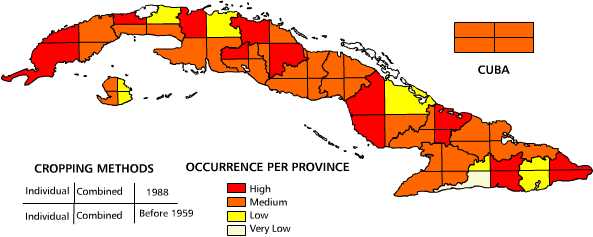

The map on crops shows the different ways in which farmers distributed the arable land. When only one crop is shown, this indicates that only one crop -- sugar cane, rice, coffee -- is grown in that land. Several crops indicate land divided into various lots growing different crops.

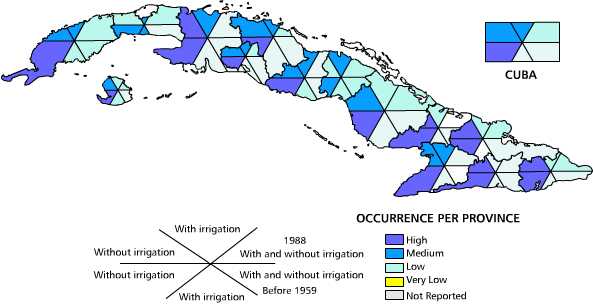

Rainfed and irrigated lands show the actual potential for the use of irrigation by the farmer. Rainfed crops show a total lack of irrigation; irrigated crops show the opposite. A third possibility combines both modalities.

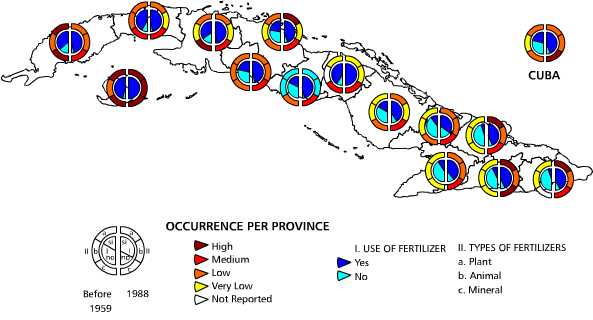

The use and types of fertilizers are shown in two forms: first, whether fertilizers are used in farmlands; the second shows the structure of fertilizers in the cases when they are used, whether of plant, animal or mineral origin.

The analysis of information having to do with tilling implements and with the various elements of the traditional agricultural system highlights their complexity and dynamics in traditional material culture. Several aspects are of great significance: native implements are still in use, to a greater or lesser degree, mostly in mountain areas; Spanish elements prevail, however, in the traditional agricultural system, with adaptations and changes according to the new environment and crops. Towards the middle of the 19th century, metal equipment was imported from France, England and the United States.

The new improved equipment was not passively accepted. Spanish and Cuban farmers chose, discarded and changed their various constructive parts according to their specific economic development, assimilating elements useful to their productive interests from a rich range of techniques and procedures.

Inv. Hernan Tirado Toirac

Maps

-

Manual digging and sowing implements

-

Manual harveting implements

-

Wooden plows (creole)

-

Mixed plows (espolones)

-

(improved) metal plows

-

Cropping plows

-

Branches & harrows

-

Plank harrow (plain harrows)

-

Yokes to draw plowing implements

-

Mortars or pounders

-

Cunyaya and sugar cane grinders

-

Stone mills

-

Iron mills

-

Winnower

-

Forms of cropping

-

Rainfed and irrigated crops

-

Use and types of fertilizers

Videos

- Food and breverages «

- Agricultural implements

- » Ways and means of rural transportation