The present study shows the function of fishermen as historical and contemporary artisan in a largely unknown culture that is sui generis and multifaceted. This research is useful not only for fishermen, but also for Cuban society as a whole, which will come to acknowledge fishing culture as a substantial element of its cultural identity.

Although the main objects of this study are fishing gear and vessels, it is also a call to the preservation of the sea and its life forms.

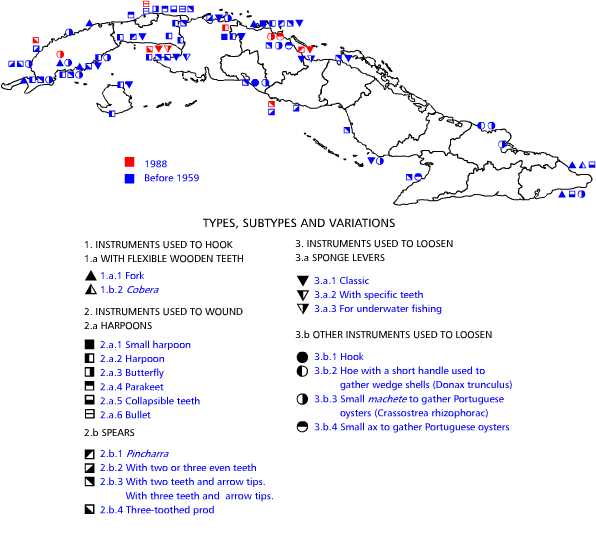

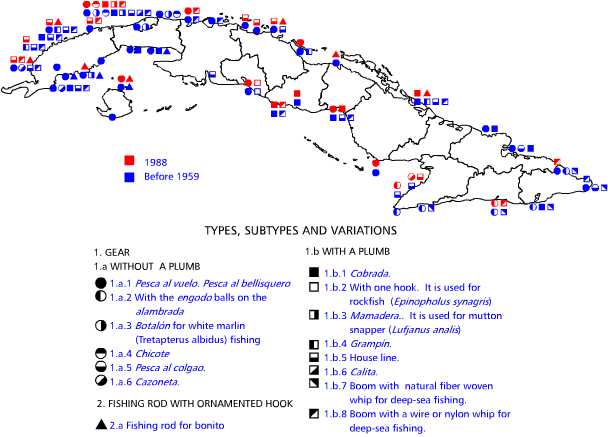

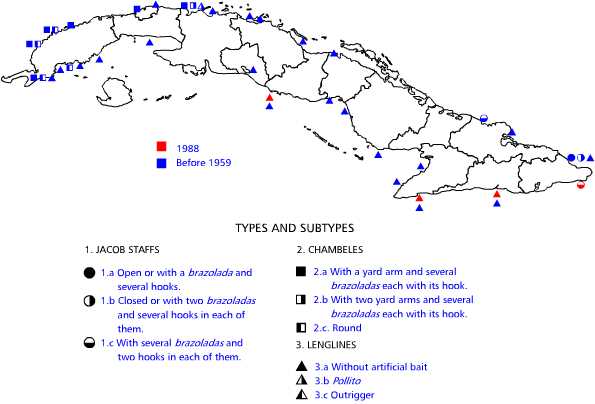

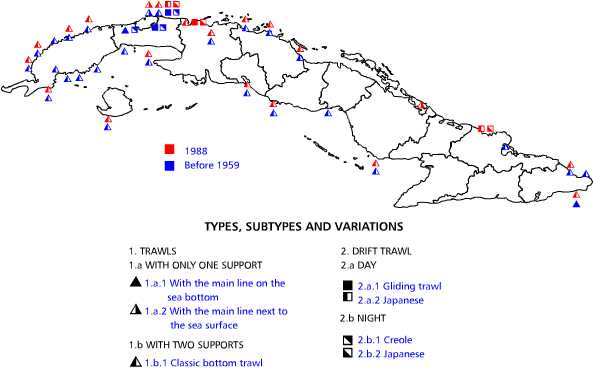

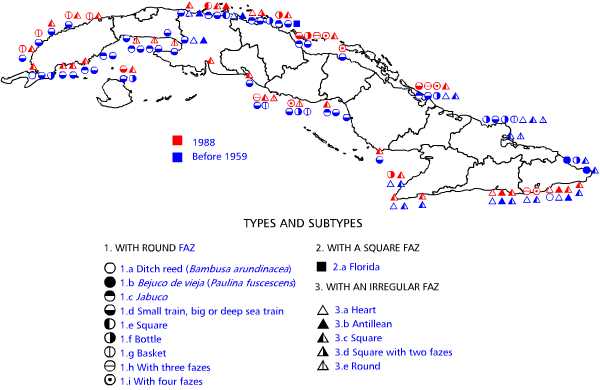

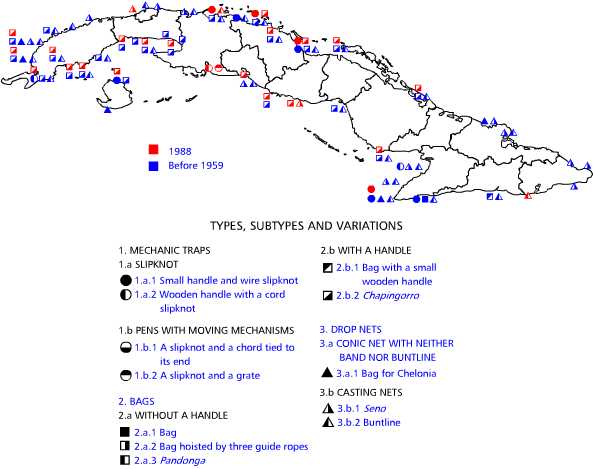

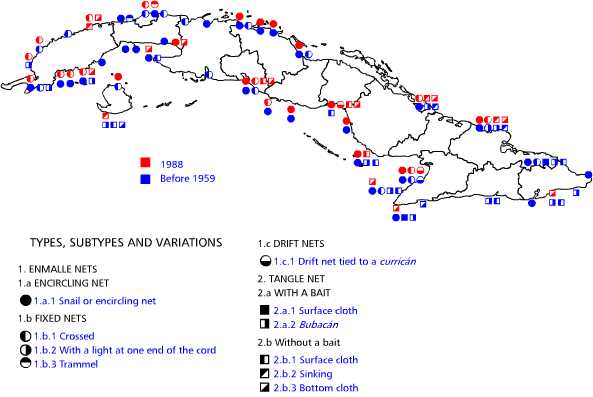

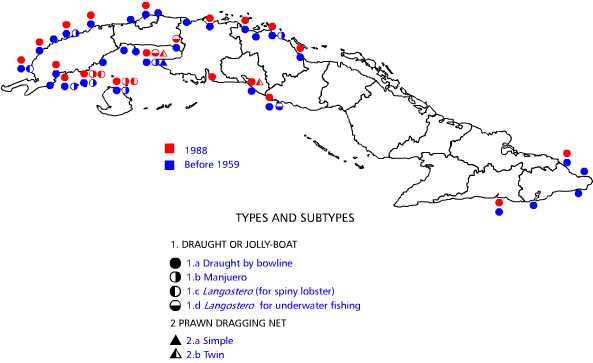

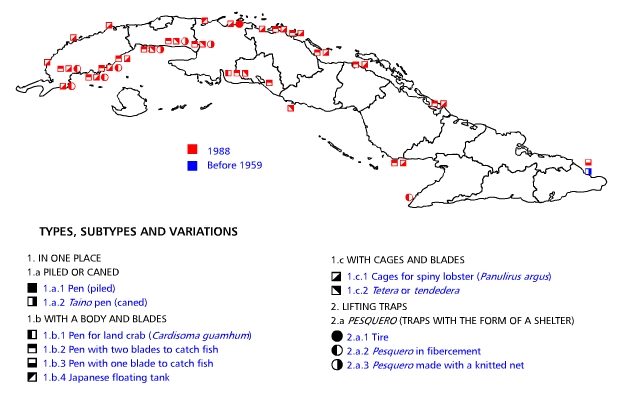

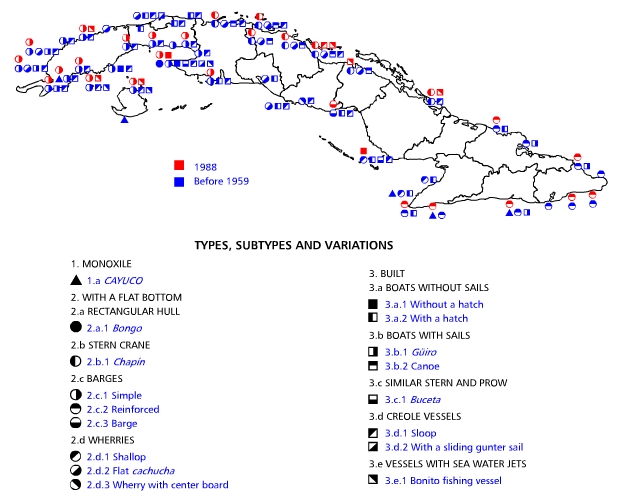

The specific purpose of this work is the study of the gear and vessels existing in the moment the research was made and the analysis of those that had already disappeared or were about to disappear as a consequence of the social and economic development of the country. There was also a need to create the typologies for each group and carry out a research into their ethnic origin and the relationship existing between old and new elements.

The methodology used were bibliographic and documentary studies and field research. Works by navigators offered valuable data on Cuban aboriginal fishing, as did other works of ethnographic, archaeologic, historic, economic and linguistic nature as well as studies on marine biology. Works by painters and novelists interested on this topic contributed to our work, but, undoubtedly, interviews with fishermen and shipwrights in all the ports in the country offered the most substantial information, together with first-hand observation, for the drawings and pictures illustrating the maps.

When the research was conducted, a large part of the types, subtypes and variations of fishing gear and vessels in the maps had already disappeared from Cuba. Thus the importance of recording them as part of our cultural heritage. Among them are the guacan or bubacan, the trammel net (three nets one on top of the other) and the cayuco. The analysis of these elements corroborated the indigenous origin of most of them. Those of Spanish, American, Japanese, Mexican and Haitian origin follow them in that order. All this was very useful for the establishment of the corresponding typologies.

These typologies were made drawing from a very wide base, since all the Cuban ports and all the variations found in the field were included in them. The main criteria for typologization were the fishing functions or principles as seen in productive activities. The terms more frequently heard from the fishermen were used to identify the various types, subtypes and variations. Most of them have to do with the forms of the caught species, the likeness with an object or an animal, the way the catch is made, their ethnic origin and others. Only exceptionally did the author use other terms, to prevent confusions or synonyms.

Apart from fishing gear and vessels, fishermen use other devices to fish, such as glasses to look underwater and bag nets, to mention only two.

Analogies and differences among the variations of gear and vessels have allowed us to identify six main historical and cultural areas: two in the southern coast, three in the northern coast and one including both coasts in the eastern region of the country.

Before the arrival of the Spanish settlers, native groups made use of water and the sea resources. Arawak fishermen used a varied fishing technology, from small spears, axes made from dog bones, to Taino pens (or corrals) and hooks made from hawkbill turtle (Erectmochelys imbrigata) shell, and nets weaved without needles, flat and with pre-Hispanic knots, among them the trammel nets, with only one wall, the guacanes or babucanes, and those with the form of a spiral for casting nets and bag nets.

They also used the baigua, a substance they put into the water to make the fish drowsy in order to catch them, as well as suckerfish, which today we know acts as a fish detector. Natives also bred sea turtles in pens or pools they made. They used cayucos and bongo as vessels. Persons with both empirical knowledge of the sea environment and resources, as well as with special skills were the ones to which this type of work was entrusted. That is why some authors have spoken about a "parceling of work".

Fishing was carried out in almost all the Cuban archipelago, although with distinct development levels consistent with the various communities in the country. Never were the sea resources harmed unnecessarily. The use of the guacan or bubacan, found in agropotter communities with a Neolithic tradition, is an evidence of this. These were nets used to catch male tortoises, while females were captured in the beach when they came out to spawn. Taino pens had enclosures to catch the largest fish, while the small catch was set free. The breeding of tortoise offers more evidence. The frailty of the gear used also contributed to the relationship between human beings and Nature.

Judging by the technical and cultural fishing gear used by the Cuban aboriginies, fishing was very diverse, and many sea species found extended throughout the Archipelago were obtained.

Spanish settlement disrupted native fishing activities in Cuba. Almost all the native population disappeared and fishing became a "focal" or "punctual" activity.

The ownership of waters and sea resources virtually passed into the hands of the owners of the nearby lands. Since the Spanish Crown did not waive its right to them, customs and law coexisted. Indians were "entrusted" to the Spanish (the encomiendas) so they would fish for them and when this type of servitude was abolished, the few Indians who had survived continued fishing. Blacks, whether slaves or not, also fished and the Spaniards gradually became involved in fishing too.

In this stage, Cuban aboriginies were more important for the development of Cuban sea fishing culture than the Spaniards. The presence of the Taino pen, the guacan or bubacan and the cayuco, among others, is a proof of this. However, Spanish and Indian trans-culturation began very early; hooks made from sea turtle shells were gradually replaced by metal ones made by fishermen and blacksmiths; new weaving techniques for nets were introduced that improved upon those of the natives, but the significance of these new techniques was constrained by the social and economic context and even by the ecological and sea conditions in Cuba, different from those in Spain. The decline in fishing activities contributed to set the stage for the underdevelopment of Cuba.

Later, social and economic transformations, at the turn of the 19th century, expanded fishing activities into new areas, like Santa Cruz del Sur, Nuevitas, Caibarien, Manzanillo and Cienfuegos. These fishing ports were important in the establishment of a fishing culture in the areas surrounding them.

The most important fishing gear during those years were those having to do with sea turtles, sponges and shell fish; there is reference to mullets being fished in Manzanillo at that time, pens were used to catch fish in Baracoa and chinchorro volapies were used in Havana. It seems that hooks were not widely used, since reference to them has only been found in Matanzas province.

In 1830 the process of transfer of ownership of waters and sea resources was concluded in favor of the Spanish government, that handed it to the fishermen in usufruct in exchange for services rendered to the Crown′s fleet. By this time, fishermen guilds had been established in most of the ports in the country and the fishermen who were registered belonged to them.

The monopoly created by the guilds increased technological conservatism, making fish scarce and costly. This situation was criticized by various scholars of the time, among them Don Antonio Bachiller y Morales, who recommended diminishing the customs duties on salt and liberating fishing activities. His opinions were consistent with the reformist ideas of the times.

The crisis in productive relations in this economic branch also became evident when fishermen not belonging to guilds were allowed to take part in fishing activities.

In the last quarter of the 19th century, fishing became a "free" activity. This implied that the work force engaged in fishing became a merchandise. From then on, the sea and its resources were considered "common property". However, as years went by, a smaller number of persons came to control the vessels, the warehouses for food and other supplies, the processing plants and the marketing of fish. Although independent fishermen did not totally disappear, they were generally under the control of middlemen and ship owners that had a higher economic status.

Towards the end of the 19th century, some fisheries, such as that of sponges, developed capitalist economic relations. For example, in the port of Havana, just one person could be in control of all fishing activities. In 1898 the number of fishermen in the country had grown threefold in relation with that of 1863. During the first two decades in the 20th century, this figure declined again because of the collapse of mercantile capitalism in that sector of economy. Already in the 20th century, as an alternative to the 1929 economic crisis and as a result of the penetration of industrial capitalism in this sector, some processing plants were established, the number of fishermen increased and so did production. However, fisheries were unimportant in the national economy. The urgent need for several studies, including the use of new fishing gear, was stated in the report of the Economic and Technical Mission organized in 1950 by the Bank of Reconstruction and Development in collaboration with the Cuban government. In the 1950s, other persons suggested similar technocratic actions, although no breakdowns were foreseen in the capitalist social and economic relations with strong feudal remnants, then existing in the fishing sector.

In the period between the last fourth of the 19th century and 1959, some cultural changes had taken place. New elements from other countries entered the fishing sector. From Spain came the drift lengline fishermen call Creole, together with the harpoon with folding teeth; from the United States came the classic sponge lever, the cane with ornamented hook and the simple net for prawns; from Mexico, the chapingorro, from Japan the day and night lenglines. Others, as the botalon and the canastro, emerged from the productive process itself. This is the moment when industrially produced hooks began to be used. The importance of cultural and technical complexes combining vessels, gear and accessories to catch a given species, as well as the spread of fishing culture in small ports throughout the coast increased.

In 1959, socialist productive relations entered the fishing sector, first in the form of fishing cooperatives and, later, as state enterprises. Fishing technology underwent a revolution. A new motor fleet replaced the sail fleet; synthetic fibers were used for some fishing gear, together with industrially produced galvanized wire nets; the number of trawls and pens grew and the number of hooks in lenglines increased; the size of nets became much larger and a Center for Scientific Fishing Research was established. Paradoxically, the cultural mechanisms for the control of sea resources weakened, as well as the secret locations of the most productive fishing areas. Thus, it is not only advisable, but required, that close attention be paid to the potential of the Cuban fishind industry. At the same time, a marked increase in indigenous fishing gear has taken place as a response to the requirements of social and economic development. Gear such as lobster trawls and two side pens have been introduced, together with gear from other countries such as Japanese floating tanks and American pots with three or four heads.

Lic. Pablo Luis Cordova Armenteros

- Ways and means of rural transportation «

- Sea fishing gear and vessels

- » Traditional handycrafts