Topics » Oral traditions

The oral transmission of ancient knowledge contributes to create the cultural bases of human communities and preserves the characteristics of past forms of life as well as social relations that have disappeared but remain important in the memory of the members of a community. The presence and significance of oral traditions in today′s complex societies contribute to the knowledge of present forms of thought and of relationships among human groups. Even with writing, the spread of literacy and the development of the mass media and its broadcasting technology, modern societies have not done away with this method of acquiring specific elements of traditional knowledge.

In recent decades, the influence of traditional forms of behavior and thought in the modern world has declined, especially in urban areas, since they often enter into conflict with prevailing ideas in a world tending towards economic homogenization and urbanization.

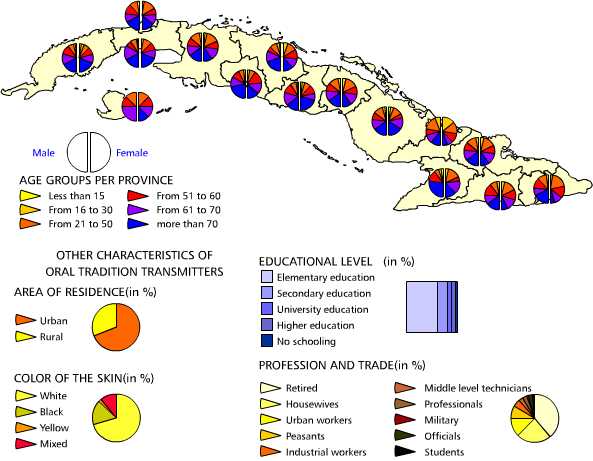

With these ideas as a starting point, a research focusing on the survival of oral traditions in Cuba was structured, covering the entire national territory, including various types of human settlements such as cities, towns and rural settlements, including disperse population. Our purpose was to arrive at a diagnosis on this phenomenon based on the elements of the smallest political and administrative cell in the country: the municipality.

With this criteria, the specific characteristics and influences in present oral transmission in Cuba were established. This information is vital for an accurate assessment of its activity and strength in social and community life, as well as in the relationships among individuals after the deep transformations that have taken place in the social and economic organization of the country in recent decades.

The specific value of ethnic characteristics in the preservation or disappearance of cultural values and traditions was also analyzed, as well as the effects of internal migrations, that have been very intense in the last forty years.

The research, carried out from 1984 to 1990, based on these premises and with the urgent objective of rescuing the most deeply rooted cultural traditions in the history of Cuban society with their regional characteristics, resulted in this set of maps offering the cultural elements that are daily transmitted orally from person to person and undoubtedly having a fundamental weight in the present Cuban society.

Since it included a wide literary sample, together with proverbs and omens, protective and healing formulae, the study offered a wide and varied panorama allowing us to draw the limits of the cultural areas in the national territory. The persistence of oral transmission and the consideration of the usefulness that the diverse genres and topics preserved or developed still have for wide segments of our population and for the collective memory of Cuban society were also taken into account.

Materials gathered in previous research made us ponder on the importance and value of oral tradition for modern societies, analyzing their influence in the daily life of Cubans, especially trying to understand why these traditions survived in spite of phenomena acting against their preservation, such as a high social mobility and the radical transformation of the traditional environment and living pace. These factors shortened the possibility of devoting time to family functions and activities for the exchange of inherited knowledge and habits focused in orality.

Every traditional cultural expression stemmed from oral and community formulations having to do with the social and economic history of the human groups that developed and maintained them in an active process of uninterrupted narration. Because of this, an abrupt break with its environment would cut their flow and they would be lost to the community that served as their basis, since they would disappear from the memory of the group.

This was, of course, our main concern during the research, since the quick pace of social and economic transformations in the country could jeopardize Cuban oral traditions. However, this situation was partially compensated by the very character of traditional culture, which survives for a long time, since it is the keeper of the ancestors′ heritage, ancestors that are very far away in time but of whom some elements still live in the sensibility and emotiveness of a community searching for knowledge and reason.

These values have been transmitted orally to the most direct descendants. With them, the deepest sense of belonging to a human group, its way of being and its capacity to reach a wider generalization were transmitted, exemplified in the many adaptations and re-modelations each of them underwent throughout the centuries and the various social transformations, in this case also having to do with non-tangible samples.

In countries such as Cuba there are also difficulties and complications in trying to find the potential origins, survivals and forms of transmission of oral traditions.

The relatively recent multiethnic composition of the population and the specific conditions and historical characteristics of each of the various migrations that for five centuries have given form to its specific culture, its specific way of being, thinking and feeling make these questions loom larger.

To learn about oral traditions, the starting point should be the specific traditional cultural elements of the members of each migrant group. Historical conditions should also be considered on a case by case basis.

On the one hand, there was the diversity of Spanish migrant groups, that included individuals with a theoretically Spanish global culture, as well as others of specific nationalities and regions within the peninsula, motivated by the search for a more secure economic situation - as happened with the Canarians and the Galicians - or by a family type migration or a migration compelled by political deportations. On the other, there were the forced entries resulting from the slave trade and the analysis of the actual possibilities of this sector of the population to maintain their traditional cultures and their non-official lines of transmission, together with the system of contracts and its variations.

Materials available reaffirmed the need to obtain more information to understand the function of oral traditions in Cuban society and life, their behavior in relation to the social and cultural transformations in the country after 1959 and the type of influence they still maintain with an assessment of their adaptation to present conditions. Actions such as the implementation of educational plans for adults and children, with a massive anti-illiteracy campaign as a first step, the creation of diversified cultural institutions in every municipality, as well as a large peasant settlement, introduced new factors unleashed by contacts between the official curricula for the nation as a whole and oral traditional culture in each region, facts that have not been analyzed in all their social and cultural implications.

The considerable increase in individual and family mobility and the migration of people from the countryside to communities and cities far from their historical habitat also offered significant elements to our study.

If the above-mentioned elements in community transformation are taken into account, the changes these factors introduced in traditional life made them be theoretically considered as elements that would potentially cause the disappearance of orality as a source of traditional knowledge and for the underestimation of its social and cultural usefulness. Reality proved that in spite of these factors tending towards dissolution, orally transmitted traditions are still in place in oral literature and in other non-tangible samples of traditional culture.

After this analysis of the materials on oral tradition in the present Cuban environment, we arrived at the conclusion that it has a different purpose from that of related expressions, offered in an institutional form, since it contains a large part of the cultural memory of the society sheltering and shaping it, according to the interests and inherited conditions of thought and life which form the basis of the idiosyncrasy and identity of a people.

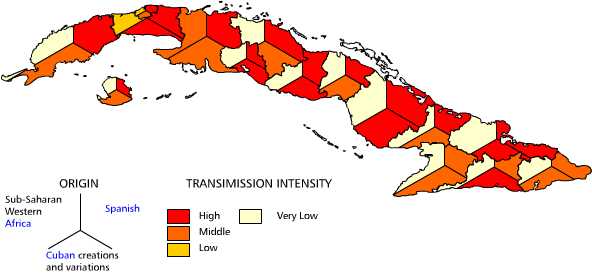

Spanish cultural components prevail in these oral traditions, together with an active trans-cultural - and at times additive - process of elements from other cultures by specific areas, as is the case with sub-Saharan western Africa. We continually found that expressions have adapted to national characteristics in several levels of integration.

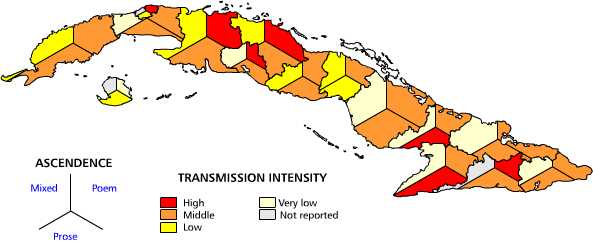

In oral literature, stories and narrations have two fundamental origins: Spanish and sub-Saharan western Africa, but both of them have modified and adapted topics and characters to make them consistent with West Indian and specifically Cuban life, with values established by the fusion or merging of distinct expressions during five centuries and the maintenance of subtle levels in relation with the importance of ethnic and cultural backgrounds, depending on the various expressions. In this way the roots of some topics and genres can be discovered.

These roots can only be perceived by those who study this phenomenon, since most of those who transmit the narrations say they come from their nearest ancestors - grandparents, parents or uncles - and in most of the cases they do not clarify their specific ethnic origin.

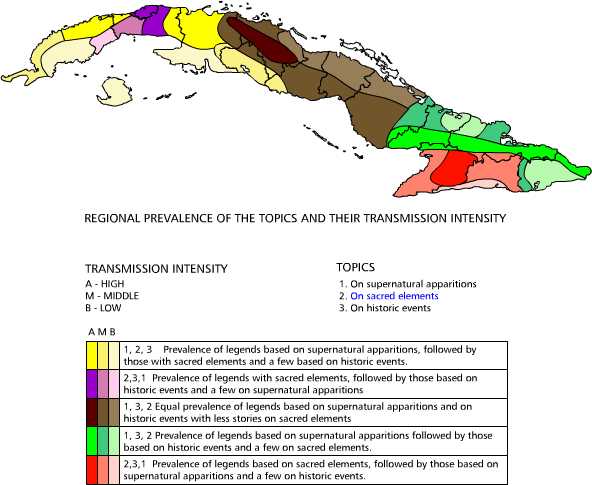

A multiform panorama is expressed in the legends, when Caribbean specificities or motives are found in legendary narrations from other places. They are found throughout the country and even when many of their topics and characters are similar to those in other areas in Latin America and the Iberian Peninsula, others emerged from interpretations of local, and especially Cuban, events.

Another interesting element is the presence of characters found in many areas of the country, such as the jigues or guijes, the chicherecus and the mothers of the water. These enter the dual terrain regarding the myths, with yet to be specified roots in the cultural complex linked to Africa, as well as in a trans-cultural process with Spain and even with our aboriginal heritage.

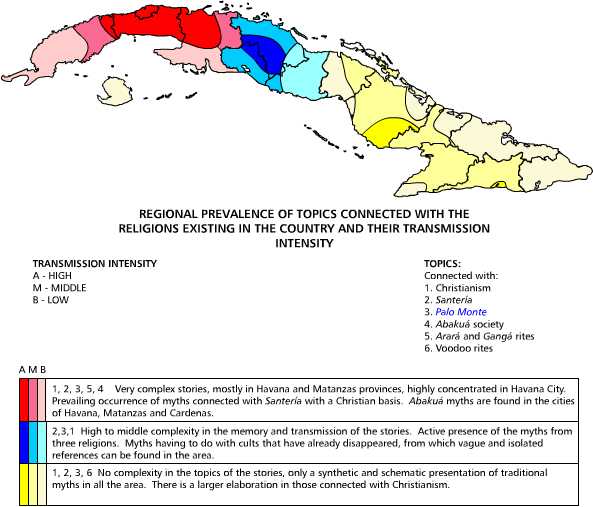

Adjustments are more subtle and complex in myths, although they are not to be considered totally Cubanized. They are in a moment of development in which they are not the original myths from Atlantic Africa, nor are they West Indian; they are in an intermediate and, thus, somewhat contradictory stage in relation with origins and results, but in a constant re-contextualization.

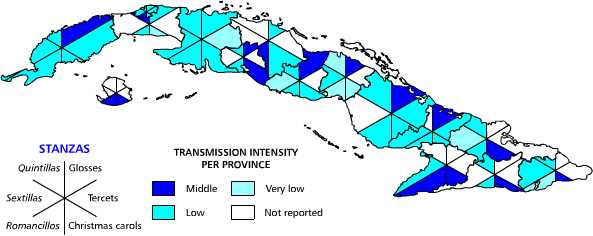

In poetry, stanzas are taken from Spanish poetic structures, with a complete consistency in meter and rime. As to the topics, their lyrics, styles and characters are also Spanish, although it cannot be said that they have not been assimilated in the country, since a large part of the decimas (ten-line stanzas), cuartetas (quatrains), redondillas (octosyllabic quatrains) and coplas (ballads) highlight and reflect daily life, even when some of the topics repeat almost without change those in Canary Island or Andalusia.

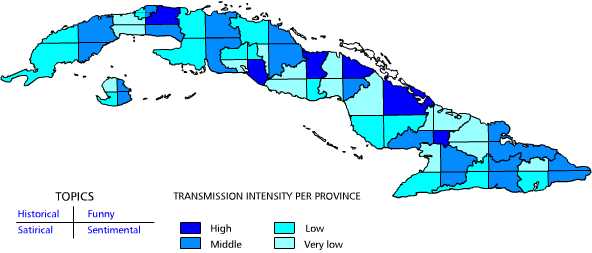

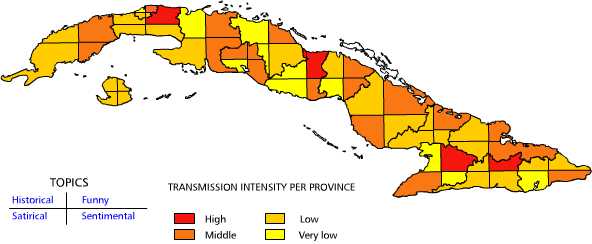

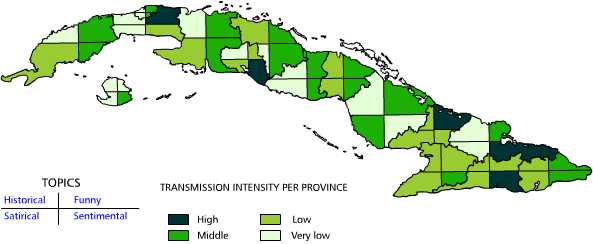

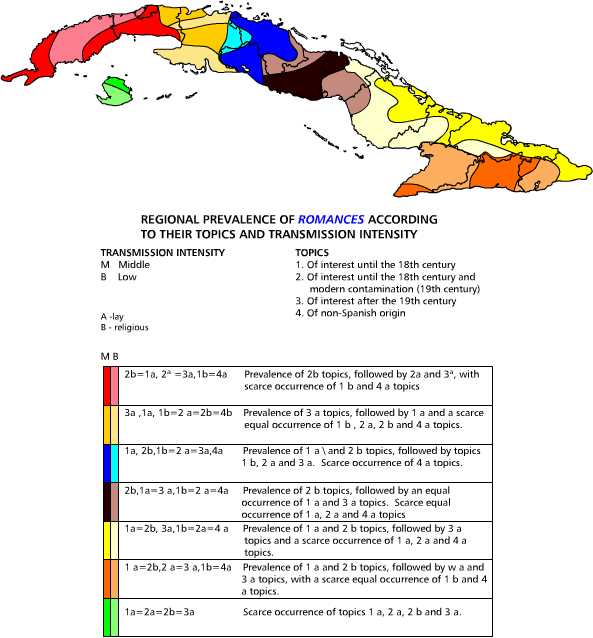

In Cuba, romances (octosyllabic verses with alterning assonant lines) maintain Spanish topics and characters, with no assimilation into regional styles or topics; they repeat Spanish variants in a more or less pure form. That is also true of the few Christmas carols that are still sung.

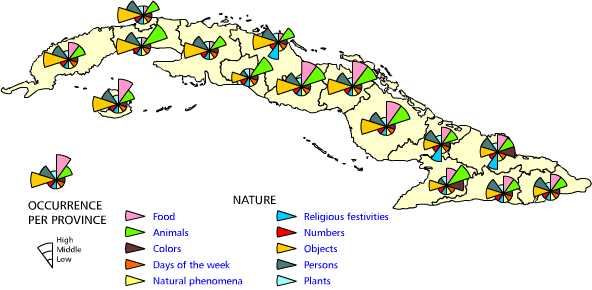

The case of stories and legends holds true for proverbs and omens: some repeat and others adapt universal topics and structures, while some others emerged due to specific traits of the Cuban historical and social perspective.

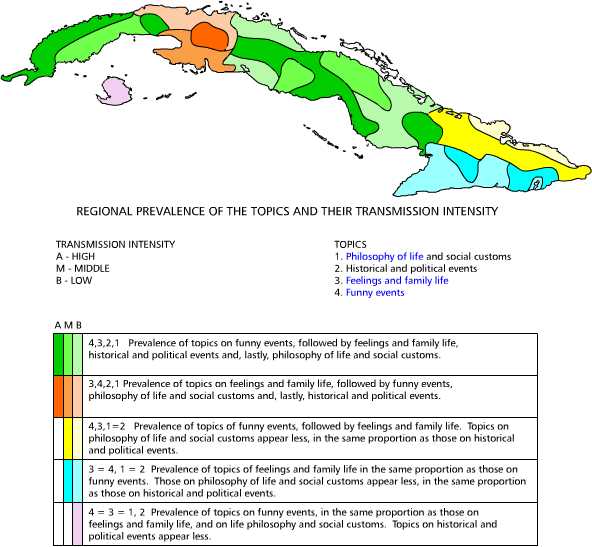

An analysis of the territorial distribution by topics and genres shows that in the case of stories and legends, people living in rural areas and small communities prefer those with fabulous and witty contents, as well as those having to do with everyday occurrences. In urban centers, humorous and satirical stories with a focus on local events prevail.

Myths are focally expressed in groups sharing the same religious beliefs, with little influence from the educational levels. They are more frequently heard in urban than in rural areas.

As to poetry, decimas prevail in rural areas and in small communities. Also, groups or individuals who migrate to the cities maintain a taste for them they transmit to their offspring. This is why there is a strong and sustained presence of the genre in urban areas dealing with the same topics they deal with in the countryside. Most of them are humorous, but in rural area sentimental topics are more frequent.

romances are sung by children until their teens and are most frequently heard in small urban populations, and not in big cities or rural areas.

As to proverbs, the teachings they offer on human daily behavior and immediate practical action serve all Cubans in daily life, with no marked differences between groups, areas or educational levels. The generalized use of proverbs by the Cuban population is of great interest to evaluate their attitudes as well as the philosophical and social opinions they hold.

Riddles are more common in rural areas and small towns. Details on educational levels or groups have not been yet researched; this will be done in another stage of this study.

Traditional beliefs are mostly held by peasants and inhabitants of small localities sharing peasant cultural traits. Educational level does influence their use and preservation, since they are more rooted in individuals and social groups with elementary education and gradually decrease with the increase in this level.

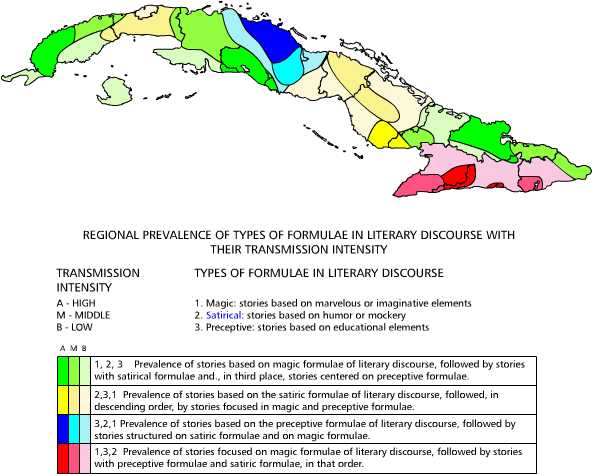

The diversity of genres studied, together with the quantity and variety of their expressions, allowed us to identify cultural areas based on styles of thought, since various topics could be grouped by genres in each region in the country, and by the prevalence of topics and tastes, together with their ethnic significance. The existence of well demarcated areas for each oral traditional expression in the country was identified for the first time.

As may be seen in the following maps, the material gathered and presented allows many analyses and approaches that the present study has not exhausted. On the contrary, they may be the basis for a general organization and assessment that will allow the undertaking of deeper studies where larger specifications, identifications and generalizations may be established, having to do with Cuban oral traditions and with similar expressions in the cultures of other peoples.

Lic. Maria del Carmen Victori Ramos

Maps

-

Stories

-

Legends

-

Myths

-

Fables

-

Décima

-

Quatrains

-

Redondillas (octosyllabic quatrain rhyming abba)

-

Coplas

-

Romance

-

Other stanzas that are not so frequenly used

-

Proverbs

-

Riddles

-

Omens and indications

-

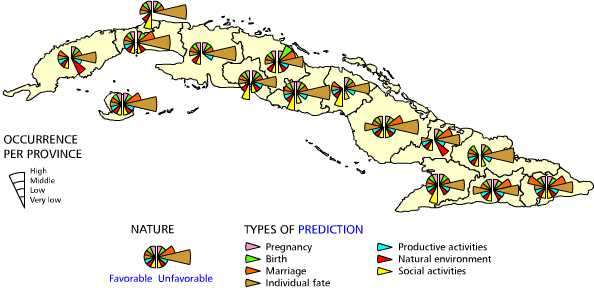

Omens. Predictions

-

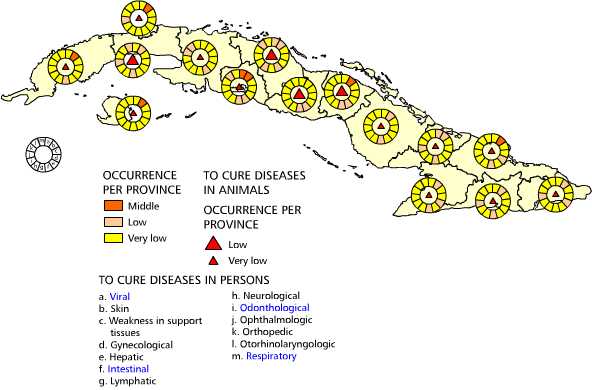

Incantations

-

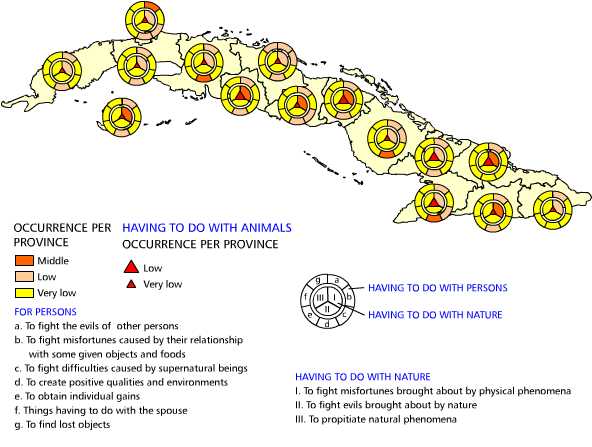

Exorcisms

-

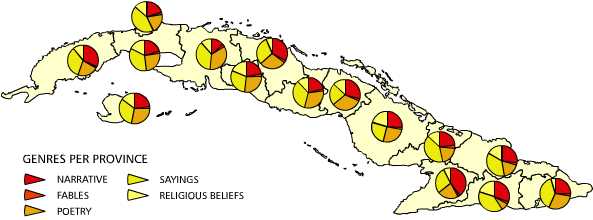

Main genres that are transmitted orally

-

Oral tradition transmitters

Videos

-

Rural story

-

Christian conception of San Lázaro

-

Mythological concept of santeria about San Lázaro

-

Flattering compliment addressed to the general aspect of woman

-

Flattering compliment addressed to woman’s eyes

-

Flattering compliment of the woman to man

Examples

-

Stories

-

Legends

-

Myths

-

Fables

-

Decimas

-

Quatrains

-

Redondillas

-

Coplas

-

Romances

-

Other stanzas that are not so frequenly used

-

Proverbs

-

Riddles

-

Omens and indications

-

Omens. Predictions

-

Incantations

-

Exorcisms

Narrations

- Traditional dances «

- Oral traditions